Could Cloned Pork Be Kosher?

Image by iStock

Along with the fact that Roger Horowitz’s Kosher USA (Columbia University Press) is compulsively readable, the book offers a meticulously researched survey of America’s kosher food industry. Part detective story, part memoir, and part academic treatise, Kosher USA brings a historian’s eye to a defining part of American Jewish life — and to a market that’s now worth billions. With the book set to debut in paperback this month, the Forward caught up with Horowitz, a food historian and director of the Center for the History of Business, Technology, and Society at the Hagley Museum and Library in Wilmington, Delaware.

Michael Kaminer: What’s changed in the kosher market since the book first came out?

Roger Horowitz: I’ve noticed three main things. The first has to do with Passover; while kosher has continued to advance in general, you don’t see big mainstream brands going for Passover kosher certification in the same way. High-fructose corn syrup, which is kitniyot, may be the issue. Companies don’t seem willing to make that change and spend on special factory cleanings.

Second, kosher restaurants mostly remain limited to cities with large Jewish concentrations. That’s a boundary. In New York City, you’ve got lots of kosher options. In places like Philadelphia or Wilmington, where I live, there are none.

The third thing I’ve noticed since the book was first published is the tremendous expansion of kosher options at colleges and universities. I don’t have a number, it’s an explosion. There’s an effort by the OU to facilitate that expansion, and it’s part of how universities are recruiting observant students.

One major development since the book first appeared is the controversy over lab-grown, so-called “kosher” pork. How is kosher law keeping up?

This is what I’d call a second-wave challenge of modern kosher law. The first wave was ingredients – the story I tell about Coca-Cola illustrates that. Can you mix ingredients from a non-kosher source and still claim a product’s kosher?

With cloning, you’re taking a microscopic stem cell from pork and growing something else. If you grow things that are unlike the product you started with, are those new things kosher? The rabbinic hierarchy is trying to figure it out, and I think that process reflects the energy and liveliness of the halachic community. It’s an intellectual process they’re engaged in, not just pulling answers out of a hat. It reflects how dynamic kosher law is.

What kinds of reactions did Kosher USA get from people inside the industry? It sometimes seems they don’t like exposure.

I’ve had great reactions from people in the industry. I spent a lot of time figuring out the manufacturing side, and looking under the hood in a way that didn’t take unfair shots. There was a lot of appreciation for that. There was some disquiet from some Orthodox because I talked about controversies and disagreements between rabbis, which can make people uncomfortable.

Has kosher become even more mainstream since Kosher USA first appeared? It was already headed in that direction.

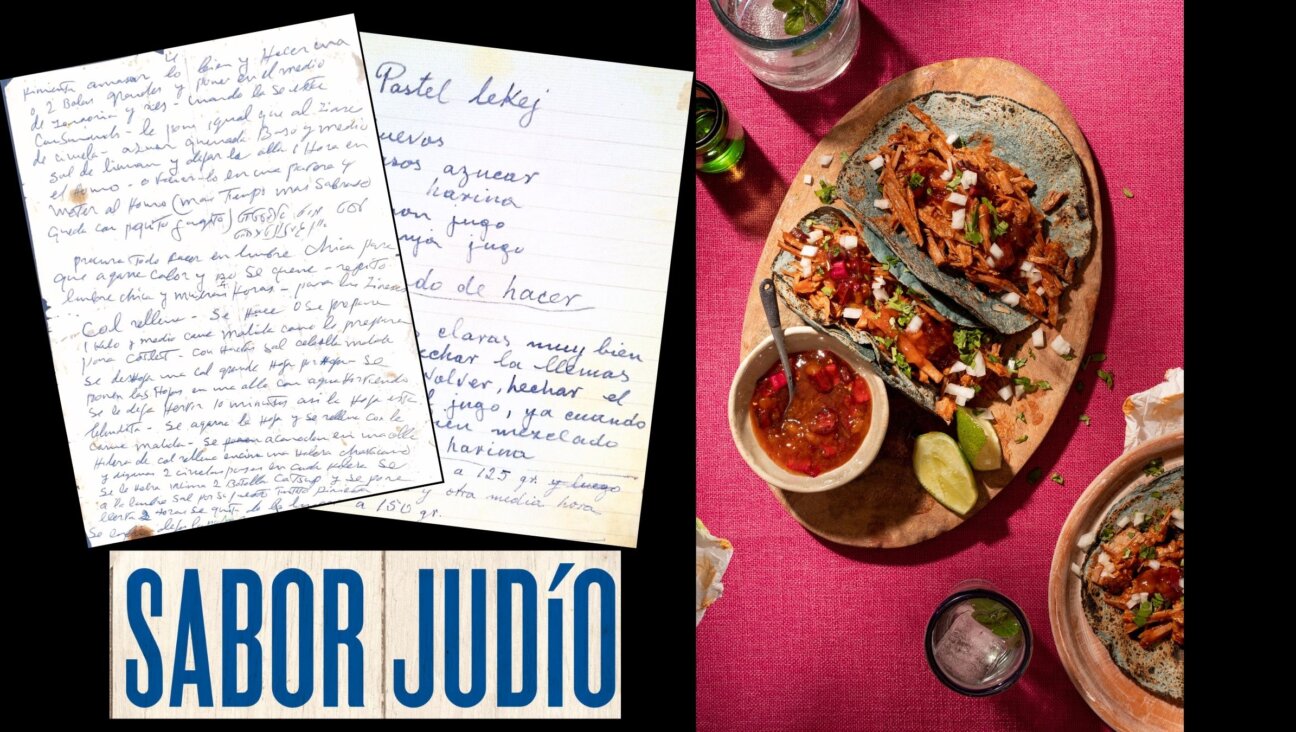

I think kosher has increasingly become another dining option in areas where it’s available. Kosher restaurants of substantial character, like the kosher Mexican on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, are packed. It’s alluring for a hip population that’s always exploring new options. Kosher overlaid with other culinary features will attract a wide audience.

Can you make a few predictions about where kosher’s going in the next decade?

One thing I see happening is multiple certifications. More products will have “kosher” on them along with labels like gluten-free. Once you’re set up for one outside certification, it’s easier to get more. Kosher’s the forerunner of this notion of getting certification to gain consumer confidence. You may see synergies between kosher and non-kosher marks.

Pressure on kosher slaughter will also accentuate over next decade, principally in other places around the world. The populism that’s dominant political trend in many parts of Europe is intersecting with greater restrictions on kosher slaughter. And it’s very troubling.

Restrictions on kosher slaughter usually come with anti-Semitic attitudes. We know this from the early 20th century, when a lot of restrictions on kosher slaughter were imposed. In the UK, the Labour Party has adopted the attitudes of a very small band of opponents of kosher slaughter. It’s now part of Labour’s platform. It requires a label on packages, which some Jewish advocates are calling a yellow star. Efforts to curtail kosher slaughter almost always intrinsically involve anti-Jewish attitudes.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO