Did Israel Really Create Falafel?

Prof. Shaul Stampfer had set out to research what bagels and falafel mean to Jews. But what he discovered on the way surprised him – and goes to the heart of Israeli-Palestinian identity politics.

Stampfer, a professor of Soviet and East European Jewry at Hebrew University’s Mandel Institute of Jewish Studies, examined the history of each food, and why they came to be associated with Jews. Both bagels and falafel are relatively modern inventions, Stampfer discovered. This runs contrary to his initial assumption, as well as to claims that Israelis appropriated falafel from the Palestinians.

“I was very surprised because when I started working I thought that this was an old, old Middle Eastern food,” recounted Stampfer in a phone interview. “When I started trying to track this down for the footnotes, it wasn’t there.”

This is not a uniquely Jewish phenomenon, he noted. “Many of what we call iconic foods are new,” he said, citing examples including British fish and chips, Egyptian koshary and Chinese-American chop suey.

His essay, titled “The Secret Lives of Bagels and Falafels,” is being published in a book titled “Jews and their Foodways – Studies in Contemporary Jewry,” to be released by Oxford University Press in January.

The discussion regarding the origins of falafel very quickly verges into the political, even though Stampfer told Haaretz that this was not his goal.

The essay focuses on falafel as a representative Israeli food, and postulates that the falafel served by fast-food stands around the country – deep-fried balls of seasoned chickpeas, eaten inside a pita along with a salad of cucumbers and tomatoes – is a 20th-century development.

Pita pockets were made possible by European baking technology likely only about 100 years old, he notes. The falafel balls themselves are also not as ancient as some sources imply: While many state that the origin of falafel is in Egypt, where it was made with fava beans by the Coptic community as early as the 4th century, falafel and its fava equivalent ta’amiyeh start appearing in Egyptian literature only after the British occupation in 1882, he found.

Oil would have been too expensive before the modern era for deep frying, Stampfer told Haaretz in a recent interview. Falafel became popular in Beirut and Mandate Palestine in the mid-1930s, and was common in Israel by 1949, he says.

Even tomatoes are a new-world food, and not indigenous to the Middle East, reaching the region only at the end of the 19th century, he adds.

Developed by Jewish immigrants

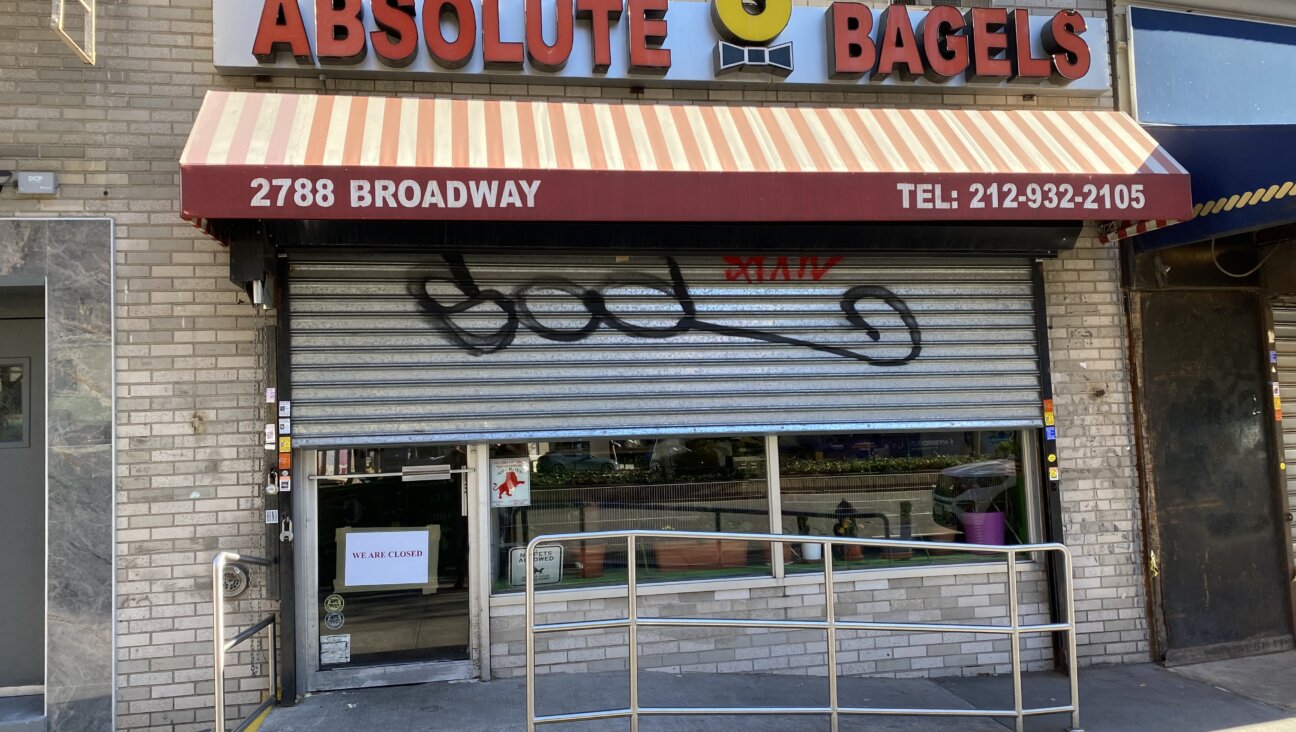

Stampfer said that also the bagel is a fairly recent addition to Jewish culinary tradition. Ring-shaped breads have been made in Eastern Europe for hundreds of years, and the word “beygal” entered the Yiddish lexicon more than 500 years ago, he notes. Yet some of these foods were more like pastries, some were made from rye and they came in varying shapes and sizes. The food that we would recognize as a bagel – a fat, round ring large enough to be sliced open and topped with fillings – was developed by Jewish immigrants in New York City around the beginning of the 20th century.

The now-traditional practice of eating bagels with lox and cream cheese is an even newer development, apparently becoming popular only after 1940, he notes.

While the United States Jewish embrace of bagels was all about nostalgia for a perceived traditional food, “the falafel combination that developed in Eretz Israel during the Mandate era was totally novel, both for the Jewish population as a whole and even more so for the East European immigrants who constituted a majority of the Jews at that time,” he writes. “Oriental” spices such as cumin and coriander made the flavor “exotic”; even the fresh salad and tahini were new to East European immigrants.

Falafel fit the immigrants’ desire to show “that you’re in the Middle East. You’re not in the old country,” he said.

Even the fact that falafel was a lowly street food suited the Jewish immigrants by being “a clear rejection of European middle-class values that required a formal meal to be eaten in the home,” Stampfer wrote.

This process of creating an identity has actually been mirrored by the Palestinians, he notes. “For some, falafel has taken on the role of a national Palestinian dish – in a sense, a mirror image of the process among Jewish Israelis.”

Some argue that falafel was an Arab dish that was appropriated by Israeli Jews – an act of cultural appropriation said to mirror other forms of Israeli violence against Palestinians. This argument rests on the assumption that falafel has a long history in the Arab world, and that Jewish immigrants to the Middle East have attempted to disregard or erase its Arab or Palestinian roots by calling it an Israeli food. Until now, a common counter argument was that many Israeli Jews are originally from Arab nations, and their ancestors therefore made falafel, too.

But Stampfer says that these arguments rest on claims that are simply incorrect. Falafel is too recent a development to have been appropriated by anyone, he writes. Yet many Israelis have accepted the Palestinian claim “that the Jews living in Israel illegitimately adopted a food of another population.”

“The eating of falafel in a sandwich was very possibly an innovation of Jews living in Jaffa or Jerusalem,” he speculates in his essay.

Despite the political implications, Stampfer says he never set out to write a political essay. “The political problems that we have here are real problems, and falafel and hummus are not the issues. The issues are human rights.”

For him, it doesn’t really matter who invented falafel. “What matters to me is that it’s used as a symbol,” he said.

Asked if his essay could add further fuel to the Israeli-Palestinian cultural debate over falafel, he responded: “I’m not out to settle scores with anybody, but I do think it’s useful to keep an eye on the facts and recognize rhetoric for what it is. What bothered me was that people got so vehement about appropriating foods” without checking facts about history.

Stampfer told Haaretz that for him, the greatest significance of falafel – and bagels – is how both foods helped Jewish immigrants to adopt a national identity in their new homelands.

“This food is saying I want to be Jewish, but I don’t want to be Jewish in the ways the rabbis tell me. I want to be Jewish in my own terms,” he said.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO