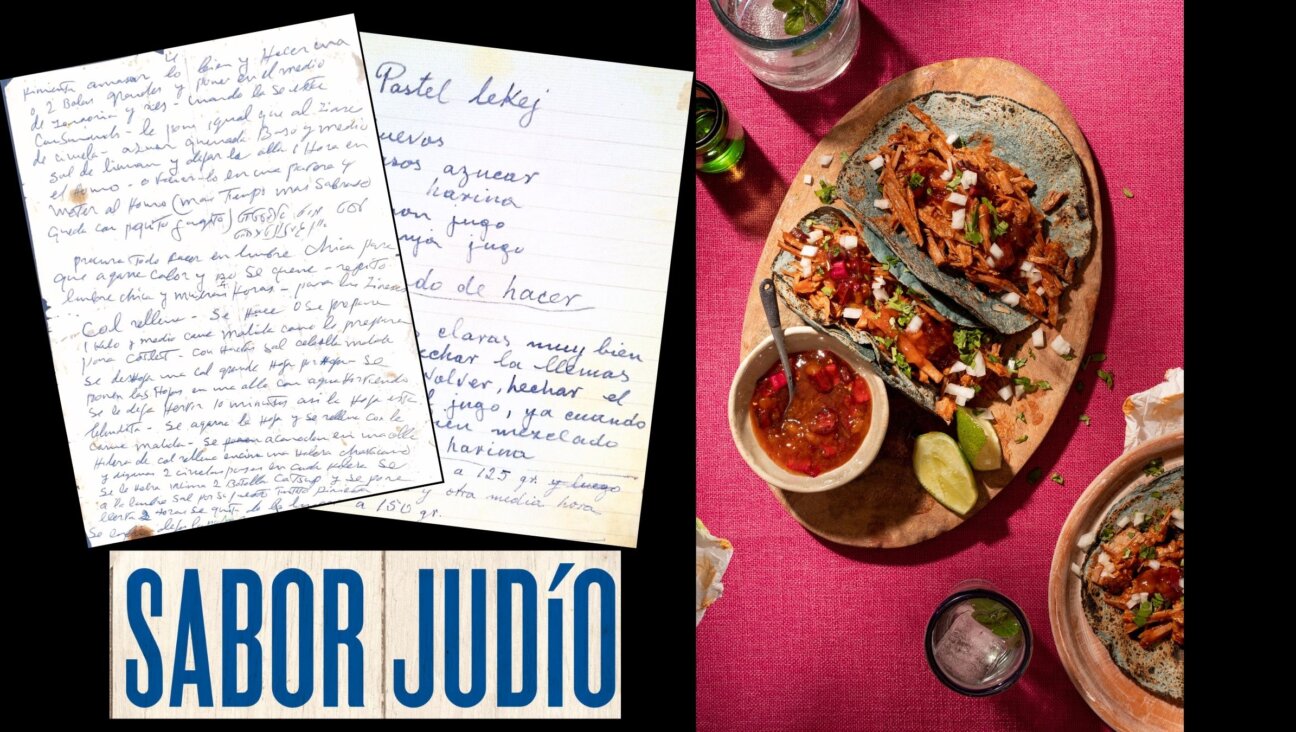

The Future of Kosher Food — In 24 Courses

Image by Courtesy of Yitzchok Bernstein

This story originally appeared in j., the Jewish news weekly of Northern California.

Imagine a perfect bite of raw, wild sockeye salmon, sprinkled with a smattering of the spice combination found on an “everything” bagel, two thin slices of celery, one or two micro sprouts on top, and a swoosh of avocado pureé at the bottom of the plate — giving it the mouthfeel of cream cheese. Add a glass of crisp chardonnay to go with it.

Now, imagine 23 more courses like this — each one small, but yes, 24 in total. The first 10 are fish, 11 through 22 are meat (with one lone vegetarian course thrown in), and the last two are dessert. Each has the same attention to detail, the same high-quality ingredients, the same use of negative space on the plate; each is matched with a wine chosen by a winemaker.

As if that weren’t enough, now imagine that the dinner and all of the wines are kosher.

An invitation to a meal like this doesn’t come around very often. I certainly had never been invited to one, kosher or otherwise, and I suppose few of you have been, either. Unless, of course, you’re one of the lucky 18 congregants of Oakland’s Beth Jacob Congregation who paid dearly for the privilege of attending this amazing affair, part of Beth Jacob’s annual fundraising auction.

Chef Isaac (Yitzchok) Bernstein, whom readers may remember as the force behind the kosher caterer Epic Bites, closed that business to take a job in New York. But things didn’t pan out, and after commuting back and forth to visit his wife and child, Bernstein is now living full-time in Oakland. He has been doing private dinners like this one (though with fewer courses) to make a living and is “aggressively” looking for a space to open a kosher restaurant. (He can be reached at [email protected]).

The 29-year-old chef has some investors lined up, though none yet are local. (He’s originally from New York, and so far, all of his investors are friends and family back East). He’d prefer the restaurant be in Oakland, but he’s open to Berkeley or San Francisco. He pictures a casual eatery by day that becomes high-end California-style at night, and it would do catering as well.

When asked why he thought he would be the right person to open a high-end kosher restaurant in the Bay Area, where every other one has failed (The Kitchen Table and Bar Ristorante Raphael, to name just two), Bernstein said, “Having a chef/owner is the only way to do it. That was the No. 1 problem with the other places, the chef and the owner weren’t the same person. No one is going to sweat like you sweat.”

But back to the 24-course tasting dinner. Bernstein, who attends Beth Jacob, offered the seats at these meals as an auction item, to raise money for the shul. There were two of these gluttonous gastronomic extravaganzas on two consecutive weekends, with 10 people each, and he invited me to the second one on Dec. 1. I had written about him before, and he wanted the meal documented.

Bernstein teamed up with fellow Beth Jacob congregant Jonathan Hajdu, the associate winemaker at Napa Valley’s Covenant kosher winery who also produces wines under his own labels. Hajdu chose all the wine pairings, which included offerings from Four Gates (the organic kosher winery in the Santa Cruz Mountains), numerous wines from Israel, a few from Europe, some of his own Brobdingnagian, Besomim and Makom wines, and what seemed like Covenant’s entire repertoire, including one bottle of Covenant’s Solomon label that goes for $150 a pop.

(I don’t want to question Hajdu’s wisdom in selecting that wine in terms of its pairing, but for the 22nd course? Given that people had already tasted 19 wines, opening the most expensive one at 1:15 a.m. when some people had gone home and others could hardly discern what they were tasting anymore, seemed almost criminal.)

Around course six, someone at the table asked meekly “Does anyone want a Diet Coke?” That was with 17 more courses to go.

The next morning, my husband and I agreed that Bernstein could have used a culinary editor. While some plates were beautiful, whimsical or genius, others had too many components and left us scratching our heads. I felt obligated to taste those last few courses, but by the end most of them went to waste, and I don’t think I need to tell you how much I hate to waste food. Bernstein had several friends volunteering their help in the kitchen. He did much of the work on Thursday and Friday, and then had only an hour and a half to prepare on Saturday night between the end of Shabbat and the start of the dinner at 7:30 p.m.

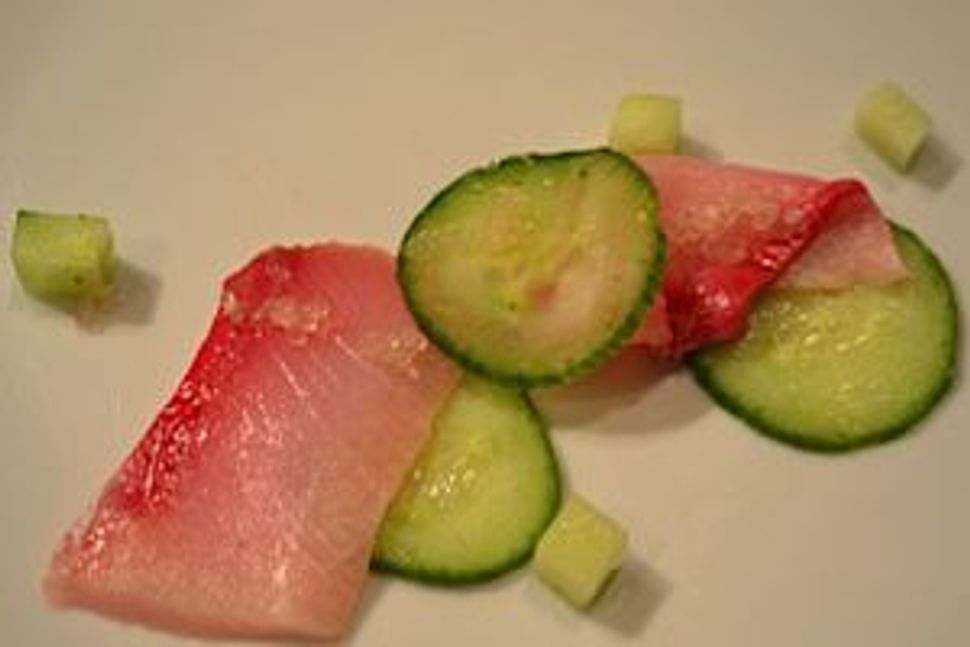

While column space doesn’t allow for a description of each dish, I can go over some of the highlights. The fourth course, which featured hamachi (Japanese yellowtail) as the star protein, was served with cucumber slices that had been pickled in gin, with a touch of Australian finger lime on top. Bernstein passed a finger lime around so we could see it up close. Oblong in shape, and colored like a regular lime, when cut open, the fruit holds clear pearls or caviar-like droplets that taste like lime, no molecular gastronomy required.

Bernstein is a big proponent of what some consider edible science experiments. “When it comes down to it, I really just want to offer ‘good eats.’ Tasty food,” he told me. “It doesn’t matter if it is on fine china with $40-a-pound Japanese fish or if it’s a bowl of buttered pasta, I want it to be as compromise-free as possible. The best products possible without blaming the kosher aspect every time I can’t do something.”

Buttered pasta, ha. Since at a meal like this, butter is verboten, Bernstein used liberal quantities of duck and goose fat to add richness. And while the fine china was left in the cupboard, several courses were served on gray rectangular slabs, causing the host to remark, “I think we should replace all of our dinnerware with slate.”

Bernstein is a big proponent of the sous-vide machine. This particular dinner featured sous-vide veal and numerous vegetables cooked with the hot water bath treatment, since it makes them meltingly tender. One dish of raw tuna nestled between watermelon slices was brought to the table covered with plastic wrap that was removed tableside, because the contents had been treated with a smoke machine. We also ate tomato leather that was made in a dehydrator, coffee and cardamom dirt, and carrot Styrofoam.

Most of the produce was organic and from local farms, sourced through Monterey Market, and whatever meat he could get came from Grow and Behold, a kosher meat company in New York that sources all of its meat from farms where the animals are sustainably raised.

A rib-eye carpaccio served with a cabernet-cherry tapenade, pistachios and a breaded and fried cube of bone marrow sent the man next to me into a reverie. “That carpaccio helped me believe in a benevolent God,” he exclaimed, both out loud and on his Facebook page, which he furiously updated with photos of each successive course. At one point, he asked one of his envious Facebook friends, “How’s your mac and cheese, b—- ?”

Bernstein admitted that 24 courses was an arbitrary number. He knew it was crazy, but crazier still, people went for it. A few dropped out along the way, and at the end, while one declared “Baruch HaShem! It’s coming to an end!” another bemoaned the fact that she didn’t wear a toga.

Of course I felt obligated to stay for the finale — I was working, after all, and I take my journalistic responsibility seriously — though it’s interesting to watch my handwritten notes from the evening go from fine to almost unintelligible. I fell on the Santoku for you, reader, and I paid the price, as I didn’t eat again until the next evening, and only began to feel normal a few days later. But I know you’re not the least bit sorry for me.

There’s no question that Bernstein is a tremendous talent, and clearly has drive and passion. If anyone can make a kosher fine dining restaurant succeed in the Bay Area, I believe he can.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO