Are charter schools public schools? The question that has divided educators now has religious implications.

The Supreme Court case that could open the door to publicly funded Jewish day schools hinges on this question, an attorney writes

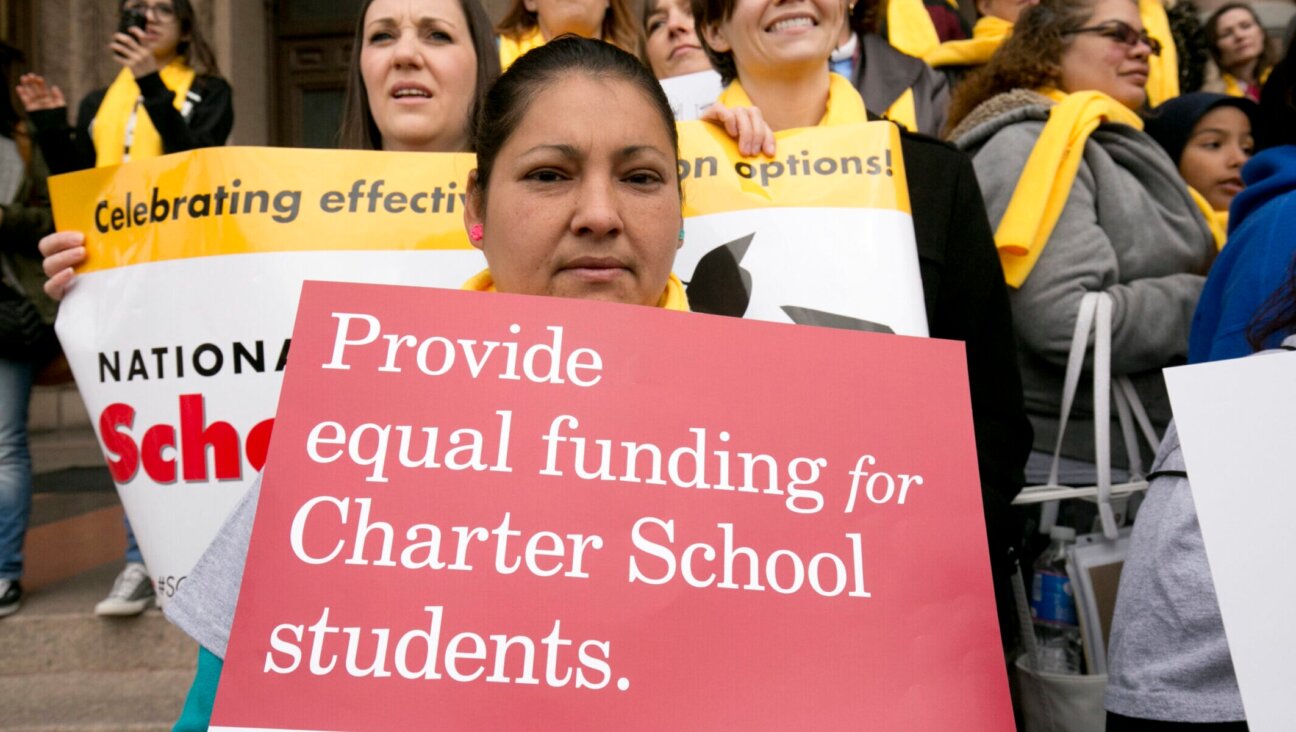

Students, educators and policymakers rally in support of charter schools at the Texas Capitol, Jan. 30, 2015. (Robert Daemmrich Photography Inc/Corbis via Getty Images)

(JTA) — Last month, the Supreme Court agreed to weigh in on the constitutionality of Oklahoma’s St. Isidore of Seville Catholic Virtual School — what would be the country’s first religious charter school.

The case has all the hallmarks of a blockbuster church-state case, addressing the constitutionality of publicly funded religious education and potentially opening the door to tuition-free Jewish day schools. But the crux of the case comes down to which path the court will pick when facing a constitutional fork in the road: Should charter schools — which are publicly authorized and funded, but privately operated — be considered public schools or private schools?

This question has divided educators for decades, ever since charter schools were developed as a strategy to improve public education. And for the Supreme Court in the Oklahoma case, its answer makes all the difference. A religious public school is likely a constitutional non-starter — even for a court like this one has shown a willingness to shift the borders of church-state separation. But under longstanding precedent, a religious private school is entitled to receive funding equal to its nonreligious private school counterparts.

Back in 2023, Oklahoma’s Charter School Board voted to approve St. Isidore’s application to become a charter school. Gentner Drummond, Oklahoma’s attorney general, described the decision as “unconstitutional,” and a “serious threat to the religious liberty of all four million Oklahomans.” The Oklahoma constitution, after all, requires the state to establish and maintain a public school system “free from sectarian control.” And Oklahoma law defines charter schools as public schools. Therefore, Drummond concluded, Oklahoma law forbids the creation of a religious charter school.

Indeed, in his view, the First Amendment — and its prohibition against state establishment of religion — prohibits Oklahoma from doing otherwise. And so Drummond filed suit to undo the Charter School Board’s decision. (He also noted that allowing religious charter schools could result in ones that he said Oklahomans would find “reprehensible,” like schools associated with “radical Islam.”)

Notwithstanding its superficial appeal, the argument moves too quickly. It may be true that Oklahoma law calls charter schools public schools. But for constitutional purposes, the relevant legal question is whether the St. Isidore’s conduct is attributable to the state. And here the structure of a charter school makes the inquiry quite messy. On the one hand, charter schools are authorized by the state. On the other hand, they are operated by private entities. So which is it?

In these sorts of circumstances, constitutional law has its own doctrine — called the state action doctrine — that determines whether an entity is public or private. But the doctrine has proven complex and unpredictable. Over the years, the court has advanced a litany of tests and considerations to figure out the answer to these questions. Lower courts applying these tests, as a result, have been a bit all over the map.

Addressing the facts of this case, the Oklahoma Supreme Court agreed with Drummond, concluding that St. Isidore ought to be considered a “state actor” because it was performing an “exclusive state function” — the free public education of the state’s citizens.

But St. Isidore has argued that the Supreme Court should, instead, focus on the state’s minimal control over the decisions and operations of charter schools. And because there is a lack of meaningful oversight over charter schools — the state has not “compelled or influenced” St. Isidore’s decision — St. Isidore should be considered a private school, irrespective of whether the state has defined charter schools as public schools, according to its argument. States cannot by legislative fiat circumvent the court’s constitutional rules for who is and isn’t a state actor — or so the argument goes. Indeed, this is why the Oklahoma attorney general immediately preceding Drummond concluded that, for constitutional purposes, Oklahoma charter schools should not be considered state actors.

Once the court decides whether St. Isidore is a public school or a private school — or, more precisely, whether it is a state actor for constitutional purposes — the rest of the court’s decision naturally follows. If charter schools are public schools, then operating a religious charter school such as St. Isidore likely violates the First Amendment as a state establishment of religion. While it is true that the Supreme Court has of late increasingly expanded the scope of permissible church-state interaction, a religious public school is likely a bridge too far. Pervasive religious instruction would likely trigger the First Amendment’s prohibition against religious coercion.

On the other hand, if the court concludes that St. Isidore’s is a private school, then rescinding its charter on account of it being a religious school would likely constitute religious discrimination prohibited by the First Amendment. Over the past decade, the Supreme Court has reiterated on three separate occasions that government cannot exclude religious institutions from funding programs available to all other comparable private institutions. As a result, Oklahoma would be prohibited from categorically excluding St. Isidore — and all other religious charter schools — while continuing to authorize nonreligious charter schools.

The court’s decision to hear the case has led many to assume that it plans to overrule the Oklahoma Supreme Court, which implies that the court does not see St. Isidore’s as a state actor. And if so, then the court would require Oklahoma to reaffirm the Charter School Board’s decision to create the country’s first religious charter school.

That being said, there may be reason to think such a decision would not open up the floodgates for religious charter schools. States continue to impose a range of regulations on religious charter schools. Those typically include, for example, a prohibition against restricting admission. So, for example, a Jewish day school that hopes to only admit Jewish students is unlikely to apply to become a charter school.

At the same time, a decision in favor of St. Isidore that reiterated the constitutional prohibition against excluding religious institutions from government funding programs available to private institutions could have significant impact. While the Supreme Court has reiterated this principle on multiple occasions, states continue to operate programs that retain religious exclusions. Indeed, in the past few months, two federal courts have deemed such ongoing exclusion of religious institutions unconstitutional — a California program that prohibited religious schools from becoming state certified special needs schools and a New Jersey program that prohibited religious institutions from receiving historic preservation grants. A Supreme Court decision that takes aim at such ongoing religious discrimination might provide added legal momentum that encourages state and local governments to repeal rules that continue to exclude religious institutions.

Of course, prognosticating regarding the court is an uncertain business, especially when it comes to doctrines as unpredictable as the state action doctrine. At bottom, though, before the court can write the next chapter in the history of church and state, it first will have to decide how to classify religious charter schools. Are they unconstitutional attempts to turn public schools religious? Or are they simply another form of religious private school entitled to equal treatment? We’ll find out what the court thinks soon enough.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of JTA or its parent company, 70 Faces Media.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO