Inside the volunteer effort to preserve the harrowing testimonies of Israel’s Oct. 7 survivors

“It is our duty to ensure that the world bears witness to these atrocities,” the October7.org website says

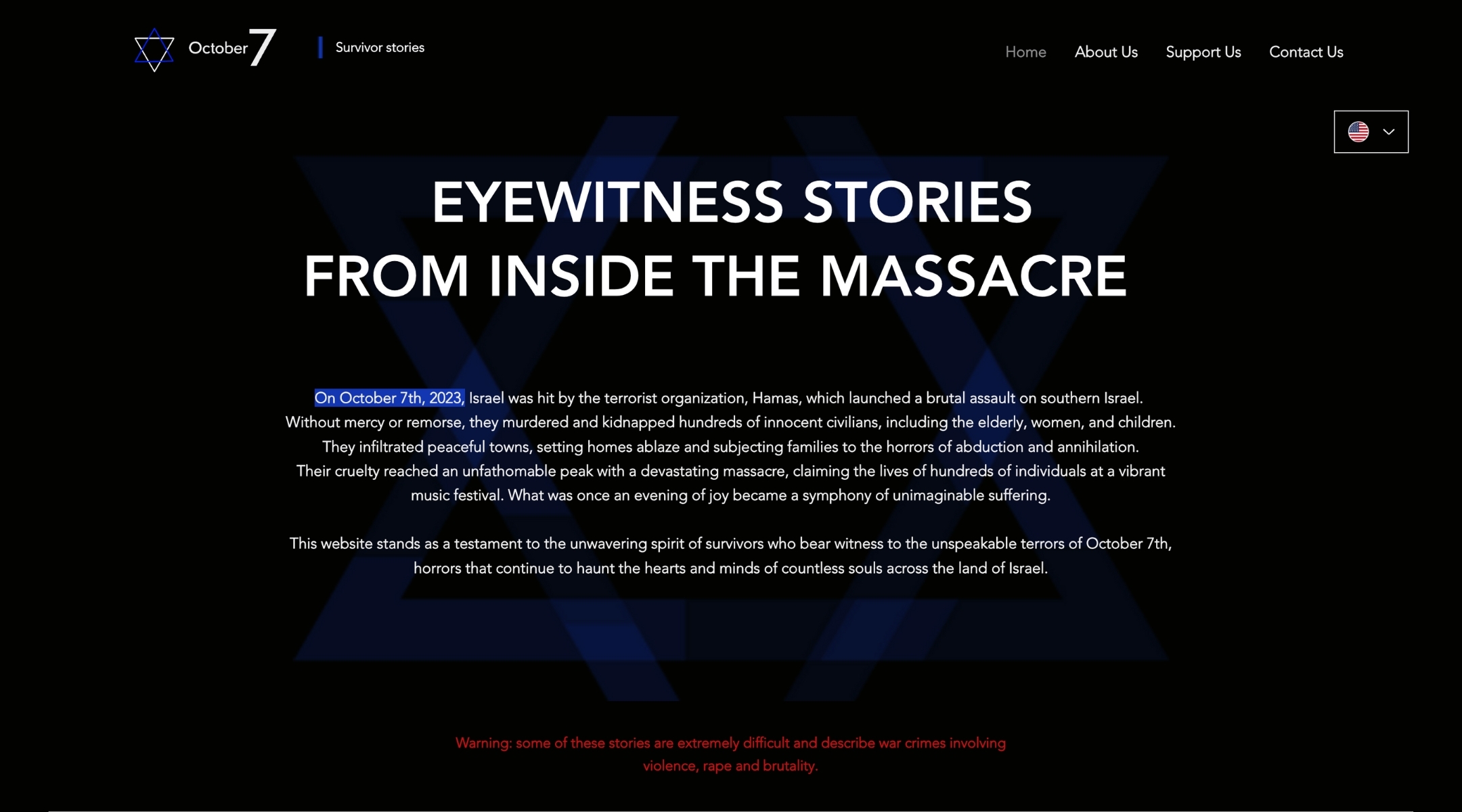

Homepage of October7.org (Screenshot)

(JTA) — Two days after Hamas killed 1,400 of his fellow Israelis, Raz Elispur saw something on social media that broke through the fog of the crisis. It was a first-person account by May Hayat, written in Hebrew, that explained exactly how she had survived the massacre at the Nova dance party.

Hayat’s account described how the day began with a beautiful sunrise and ended with her fleeing Hamas captors who murdered a man in front of her, then covering herself in the blood of other victims to play dead until rescuers arrived hours later.

“It was the first time that we read content from someone, first person, with a face, with a name told from her perspective that tells everything and shares everything,” Elispur told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

Elispur, a video editor who lives in Tel Aviv, was inspired to take action. Working with his sister, Adi Clinton, he began reaching out to survivors within their own networks to offer to take down their stories. Soon, the project spiraled into something even more ambitious: a sweeping effort to collect survivor testimonies on a website whose name is simply the date of the devastating attack.

“We built this website to make sure that the stories of survivors who endured these unimaginable horrors are never forgotten,” October7.org says. “It is our duty to ensure that the world bears witness to these atrocities.”

Elispur is often awake until 3 a.m. on Zoom calls with small groups of volunteers from around the world to coordinate the collection, translation, and publication of the stories, which include the first names and last initials of the survivors along with photos and videos from the time of the attacks.

In one story, a soldier describes the daylong ordeal that reduced her army unit to just seven survivors. In another, a man recounts how he and his running partners initially thought they had been saved by soldiers, only to see both of them murdered by Hamas terrorists. In a third, a woman describes escaping captivity, where her neighbor says she saw her baby daughter shot in the head, with the help of soldiers who fell around her. Many of the testimonies are from the nature party, where 260 bodies were recovered.

So far, the website has published 100 testimonies, and the number is growing by the day. Some survivors are submitting stories directly, and others first appeared in the Israeli press.

Elispur sees the enterprise as both a way to be useful at a time of communal service and to provide a direct benefit to survivors.

“For them, it’s also a way to just let it out, I would say,” Elispur said. “But for me, and also for my sister — I think for everyone that read it — when you read it, you can relate to it and you could imagine yourself in the same scenario, as horrible as it might sound.”

Given the number of casualties during the Hamas attack, Israeli media has been flooded with obituaries. Survivor testimonies play a different role. For one thing, they can for obvious reasons offer more details about the assault that Israeli civilians faced during the deadliest day for Jews since the Holocaust. They also can offer an antidote to denial and distortion in a climate of misinformation.

Survivor testimonies have been a crucial part of Holocaust education for decades, under the theory that hearing from people who lived through atrocities is a vital component of guarding against future genocides. Now, one organization that has been collecting Holocaust survivors’ testimony for the last three decades has announced that it is also taking testimony from Oct. 7 survivors.

“At such times, it is essential that we do not give ground to despair,” the University of Southern California Shoah Foundation said in a statement. “We have a duty to bear witness, to remember, and to act. We must learn from the experiences of those most affected, particularly the survivors of this deadly genocidal hatred.”

So far, everyone the October7.org team has reached out to for testimonies has agreed to have their story shared.

“People are thanking us and [saying], ‘Please spread it to the world, please do it,’” Elispur said.

To make the stories widely accessible, they need to be translated — and not by an automatic translation service, which can make errors and, crucially, lose the emotional tenor of the original. The October7.org team includes volunteer translators with knowledge of Japanese, English, German, Arabic, Spanish and French and is producing stories in each language.

While he says managing the website is tough, Elispur knows the translators have the toughest job because they read the stories so closely, watching as the narratives transition from descriptions of the “best party ever” to scenes of mass death.

“It’s super hard for them,” he said. “If I take responsibility for one person that reads more than two or three stories a day, I will feel guilty. I myself, when I post those stories, when I do the technical job, for me, it’s hard.”

The team repeatedly encourages each other to take breaks and spend time with their children in between translations. But the work, too, is a sort of salve in a time of great pain, Elispur said.

“Nothing we can do will bring back the 1,500 people that were murdered,” he said. “Nothing we can do will bring back my friend’s parents. But if you feel that you did a bit, it helps.”

This article originally appeared on JTA.org.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO