Richard Barancik, last of the ‘Monuments Men’ who recovered art and treasure looted by the Nazis, dies at 98

The 20-year-old volunteer, later a renowned architect, was awed by the experts in fine art who led the recovery corps

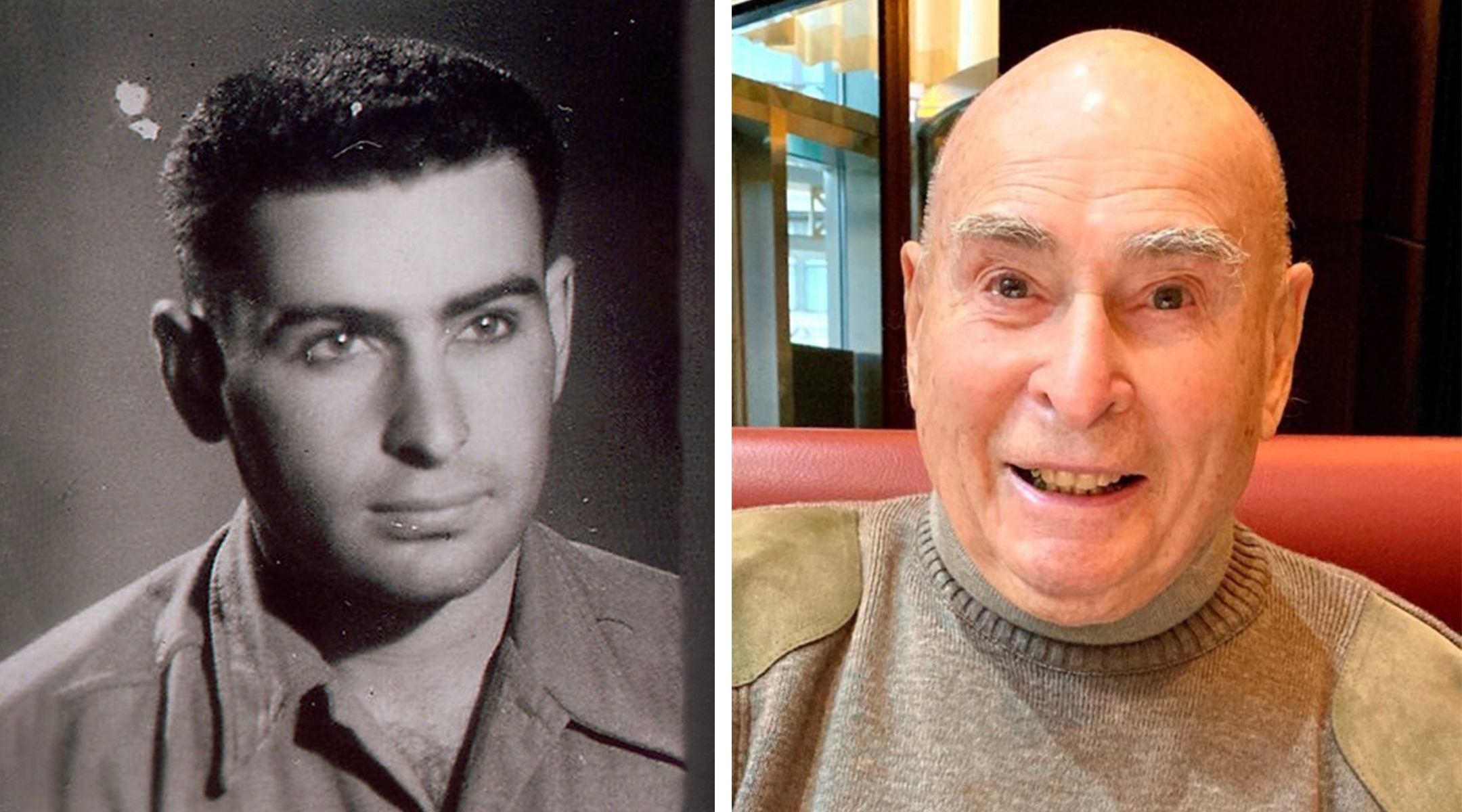

Private First Class Richard Barancik joined the “Monuments Men” in 1945; after the war, he became a prolific architect in Chicago. (Monuments Men and Women Foundation; Dignity Memorial)

(JTA) — Richard Barancik, the last surviving member of the Allied military corps that hunted down and recovered countless artworks stolen by the Nazis, died July 14 in Chicago. He was 98.

As an Army private first class and member of what was officially known as the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives (MFAA) Section, and unofficially known as the “Monuments Men” (although it included a few women), Barancik was dispatched to Salzburg, Austria in 1945. He and a fellow soldier assisted in moving stolen art treasures to the central repository of the U.S. Property Control Branch and served as guards.

Although he would go on to become a prolific architect after the war, the 20-year-old Barancik volunteered for the MFAA only with training in basic engineering and a love of art.

“When I arrived in Salzburg, I was not only overwhelmed by the beauty of the town but the quality of the men in the Fine Arts Section. They were typically older and very well educated in the fine arts,” he said in an interview last year.

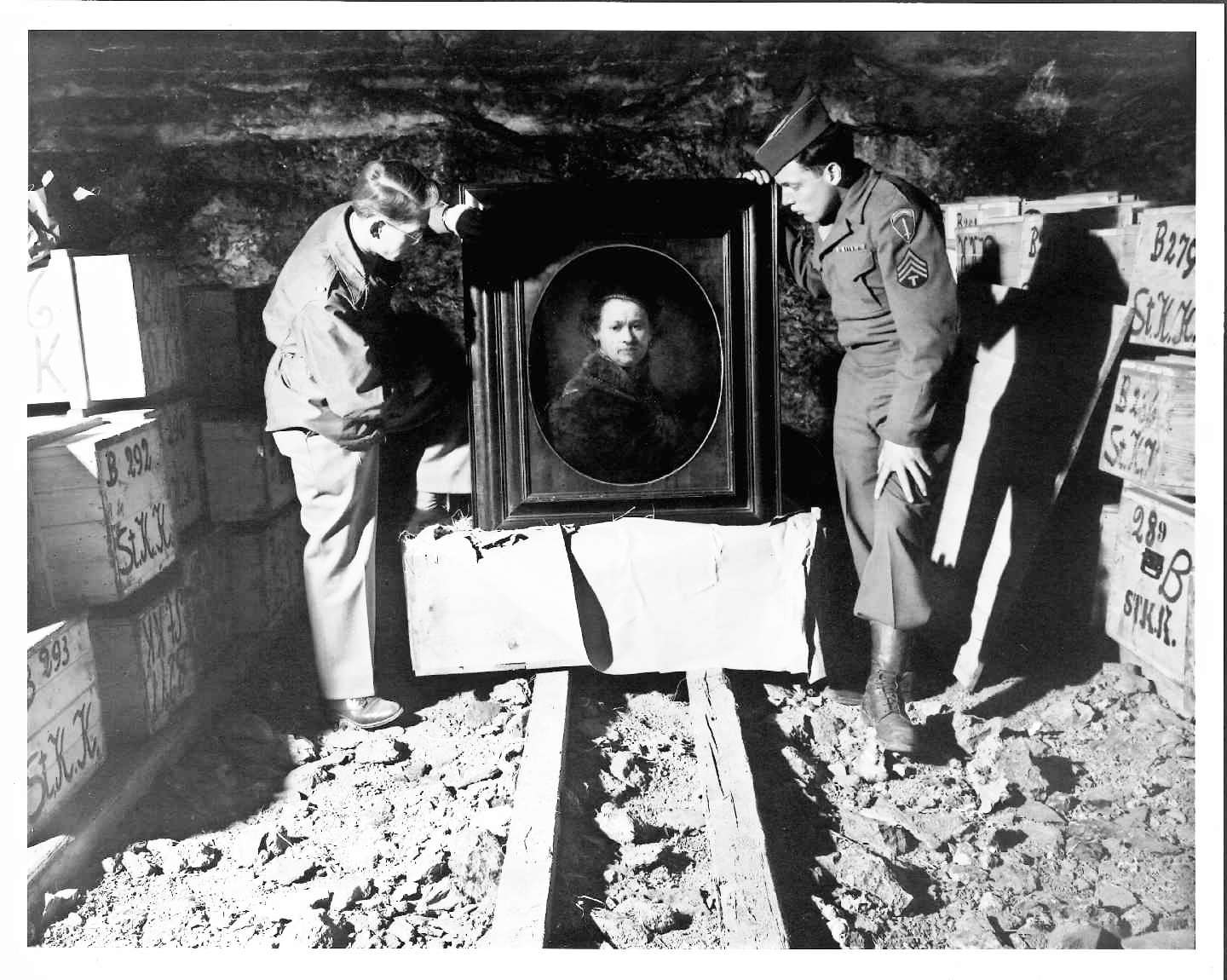

All told, about 350 men and women, mostly academics, art historians and other antiquities experts, served in the MFAA, mostly from the United States and Great Britain but nearly a dozen other countries as well. Between 1943 and its dissolution in 1946, the Monuments Men recovered thousands of paintings, sculptures, gold and other cultural objects in both Europe and Asia — a rescue effort that allowed Jewish survivors, the families of victims and others who had been stripped of their assets by the Nazis to recover many of them in the decades after the war.

Harry Ettlinger, right, and Dale Ford, U.S. soldiers who served in the Monuments Men, are shown in 1945 or 1946 inspecting a Rembrandt self-portrait in a salt mine where the Nazis stored stolen and hidden art. (Courtesy National Archives and Records Administration)

After the war but while still serving in the military, Barancik attended Cambridge University in England and the Ecole des Beaux-Arts at Fontainebleau, France. He returned home to finish his architecture degree at the University of Illinois. The firm he founded in 1950 with a former instructor, Barancik Conte & Associates, designed private homes, office buildings, campuses and bowling alleys, and eventually became known for distinctive high-rises along Chicago’s upscale “Gold Coast.”

He retired in 1993 and split his time between Pebble Beach, California, and Chicago. He served on the boards of the Latin School of Chicago, the San Francisco Asian Art Museum, the Monterey Institute of International Studies and the Monterey Museum of Art.

In 2015, Barancik was part of a delegation of former Monuments Men who traveled to Washington, D.C., to receive the nation’s highest civilian honor, the Congressional Gold Medal. “This is a small group of people who, acting purely on their passion and courage, reclaimed the world’s most valuable treasures,” Rep. John Boehner, then Speaker of the House, said at the ceremony. “They reattached the tendons to the bone that is a civilization’s identity.”

Barancik was born in Chicago in 1924. His mother, Carrie Grawoig, was an immigrant from Russia who gave piano lessons; his father, Dr. Henry Barancik, ran a hospital division in France during World War I and was chief of staff at Jackson Park Hospital and South Chicago Hospital, according to the Chicago Sun-Times.

Barancik is survived by two sons, three daughters, four grandchildren and three great-grandchildren. He was divorced once and widowed twice.

“Richard was larger than life, a true original who defied convention,” his family remembered in a tribute. “He had an impeccable eye for art and design, no matter if it was high or low. He knew what he loved… and surrounded himself with those things, whether they were paintings, ship models or miniatures.”

This article originally appeared on JTA.org.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO