He racked up millions of likes for being a proud gay Haredi. Then he was outed as a fake.

‘I’m extremely upset that he is falsely portraying an experience without the nuance of living it,’ one person commented

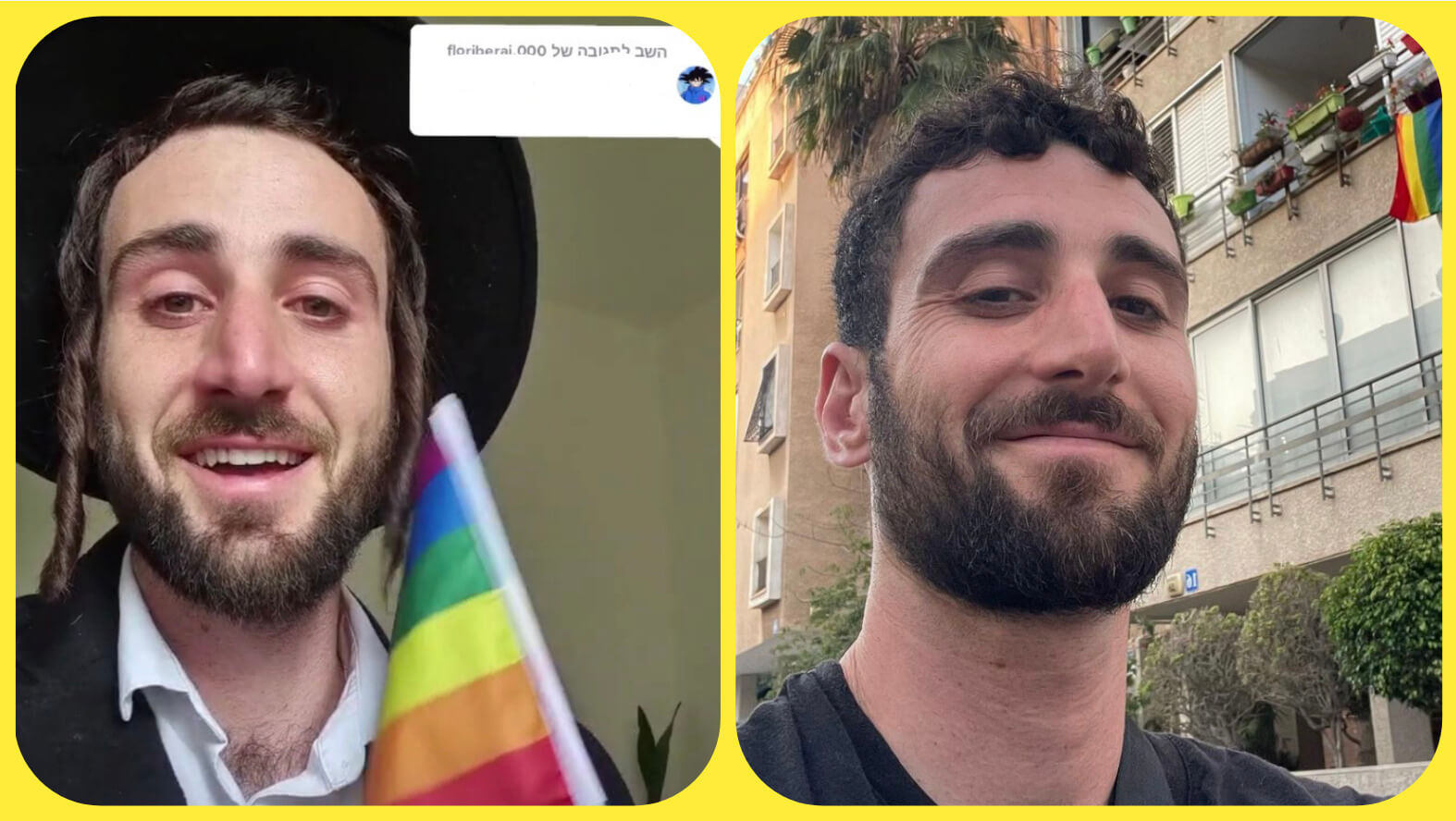

Yaakov Levi, left, was the moniker of a popular Haredi TikTok account revealed to be a secular Israeli named Erez Oved. (Screenshots via TikTok/@this.is.kosher; Instagram/@erezoved) Illustration by the Forward

His social media presence was nothing short of shocking: an Israeli man, in Haredi garb and payot, peacocking as an out gay Jew on TikTok and Instagram.

Identifying himself only as Yaakov Levi and going by the handle @this.is.kosher, he gyrated to pop anthems, paraded with a rainbow flag, and clapped back at homophobic comments, attracting more than 160,000 TikTok followers, 2 million likes and and countless admiring messages.

His self-acceptance and defiance of the Haredi world, where modesty is a virtue and gay relationships conflict with religious law, delighted many of his fans. But on Thursday, the account — and the payot — were revealed as fakes.

Listen to That Jewish News Show, a smart and thoughtful look at the week in Jewish news from the journalists at the Forward, now available on Apple and Spotify:

A Twitter thread connected the account to Erez Oved, an Israeli actor who is gay and Jewish but not Haredi. The bio of Oved’s account links to the TikTok.

The revelation enraged LGBTQ+ Orthodox Jews who felt their experience had been appropriated for fame.

“When I was a Haredi gay kid, I couldn’t just take off my peyos and my black hat,” Shlomo Satt, whose thread unmasked Oved, wrote on Twitter. “It was a constant struggle and I was reckoning with it 24/7. I’m extremely upset that he is falsely portraying an experience without the nuance of living it.”

When I was a Haredi gay kid, I couldn't just take off my peyos and my black hat. It was a constant struggle and I was reckoning with it 24/7. I'm extremely upset that he is falsely portraying an experience without the nuance of living it.

— Shlomo Rozenek (@shloze) June 15, 2023

“I fell for it. And I was so happy to see that LGBTQ representation on TikTok,” another Twitter user commented. “And now this just makes me sad and angry.”

After the thread attracted attention on social media, Oved posted a message to his Instagram story: “We live in a terrible reality. I came to fight and try to change people’s lives ❤️?️?.”

Oved responded to a request for comment a Forward reporter Saturday, after this article was published. In a series of messages, he said he created the character following his own struggle with coming out.

“I discovered that as hard as it was for me, I was lucky, and that if I had been born into a Charedi family, the difficulty would have been much greater,” Oved wrote. He said he kept his real identity secret to maximize his intended impact: “Be the voice that it is OK to be Charedi and gay, for all those who can’t make their voices heard.”

He did not offer an apology, but said he was “ready and willing” to receive feedback. He said he would decide soon “in what form to continue spreading this important message.”

Social media has partly lifted the curtain on the insular world of Haredi Judaism. Some popular TikTok accounts explain the rituals of Orthodox daily life. Some simply show Haredi people doing regular activities — putting on makeup, dancing to music and talking about their day jobs. The accounts connect Orthodox Jewish people to each other as well as demystify them to non-Orthodox and even non-Jewish society.

But the Yaakov Levi videos were also a rebellious political statement. He proudly shared both his sexuality and his purported religious identity, sending the message that they were not in conflict — and juxtaposed them for maximum effect. Between his white shirt and his black suit jacket, he showed off rainbow suspenders. Searching for a yarmulke in one TikTok, he mutters “not gay enough…not gay enough…not gay enough,” as he sifts through mountains of black velvet — then picks one festooned with pink sequins.

Without ever conceding that the page was an act, Oved painted a picture of the Haredi world that was more tolerant of queer Jews than its reputation suggests. He introduced two women in modest Haredi dress, identifying them as his cousin and his mother. Both were accepting of his orientation. In one video, the latter said people who weren’t accepting of her son “can go to hell.” Oved told the Forward the woman was his actual mother. Other people playing family members were actors, he said.

The reality is often very different as Haredi Orthodoxy regards sex between two people of the same gender as a grave sin. Some gay Haredi Jews stay closeted in their home communities; others leave Orthodoxy entirely.

In an interview, Satt said he grew up in Far Rockaway, New York, in a Haredi home that did not have internet until he was in ninth grade. When he reached bar mitzvah age, he started wearing a black hat. At around the same time, he realized he was attracted to other boys, but understood it was incompatible with his religious observance. He did conversion therapy for three and a half years, which he now describes as the worst experience of his life. When he finally came out, some family members disavowed him.

“Every single one of us has struggled mightily. Every single one of us has lost some degree of connection to family because we’ve come out” in the Haredi community, Satt said. “Trying to portray the community as he’s this anomaly is not correct, and it does a lot of harm for the Haredi community, because in order to make progress, you need to be aware of the problems.”

Editor’s note, Jun. 18: This story has been updated to include comments from Erez Oved.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO