He saved 2,500 World War II refugees — but doomed his career as a diplomat

Proposed legislation would honor 60 diplomats who rescued Jews, including Hiram (Harry) Bingham IV, US vice consul in Marseille

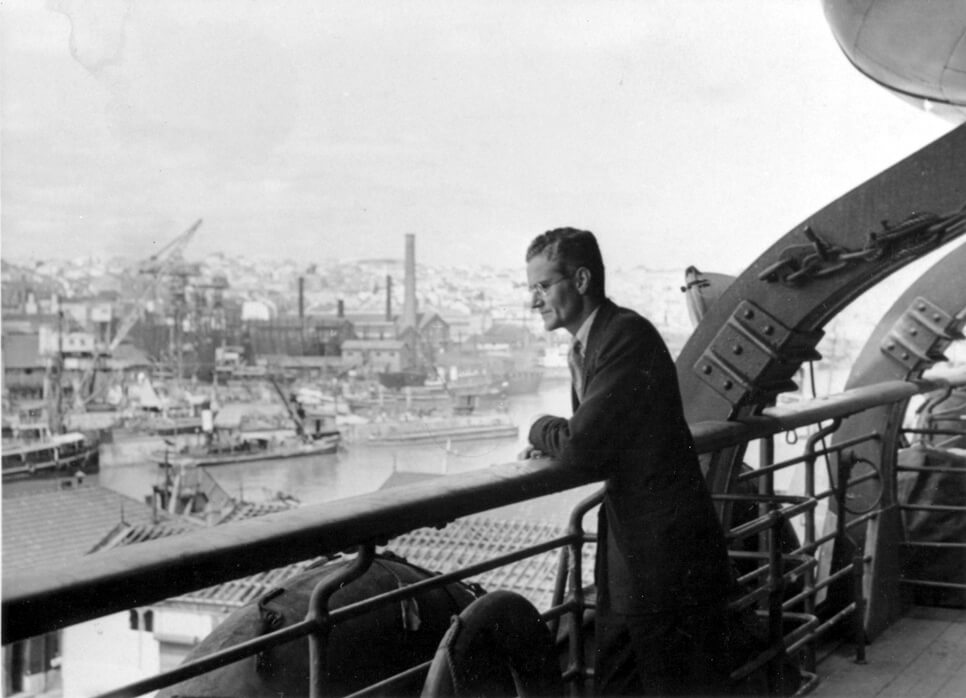

Hiram (Harry) Bingham IV overlooks the port in Marseille, France. Courtesy of Kim Bingham

Hiram (Harry) Bingham IV was a vice consul at the U.S. consulate in Marseille, France, when the Nazis invaded in 1940. Over the next 10 months, Bingham helped 2,500 refugees flee by signing visas, processing paperwork and challenging U.S. anti-immigration policies. Among those he saved were Hannah Arendt, Max Ernst and Marc Chagall.

His activism doomed his career. In 1941, the U.S. State Department transferred Bingham out of France. When the war ended, he moved home to a Connecticut farm to raise his family.

Now legislation proposed by two U.S. senators would honor 60 diplomats from around the world — including Bingham — with posthumous Congressional Gold Medals for their courageous work on behalf of refugees during World War II.

Bingham is one of two Americans on the list, which also includes Aristides de Sousa Mendes of Portugal. Sousa Mendes was stationed in Bordeaux; he was recently posthumously honored in Israel. The other American is Raymond Geist, who issued visas for German Jews as consul and first secretary of the U.S. embassy in Berlin, 1929-1939.

The Forgotten Heroes of the Holocaust Congressional Gold Medal Act was introduced Jan. 26 by Sens. Bill Hagerty (R-Tenn.) and Tim Kaine (D-Va.). It would posthumously award a Congressional Gold Medal to honor diplomats who “took heroic actions to save Jews fleeing Europe.” The legislation notes that many of these diplomats “had strict orders in their home countries to not aid the Jewish population,” yet they issued passports and visas anyway, set up safe houses and even confronted Nazi officials.

Bingham was “the one man at the Consulate” who understood that his job was “not to apply the rules rigidly but to save lives wherever he could,” the famed American rescue worker Varian Fry said, according to a tribute to Bingham on the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum website.

He was “trying to literally save lives against orders of his superior,” his daughter Abbie Bingham Endicott, one of Bingham’s 11 children, said in an email to the Forward. “He chose to save lives when he could, even if it might cost him his career, and he suffered from knowing he couldn’t help everyone.”

Bingham was honored in 2002 with a posthumous “constructive dissent” award on behalf of the American Foreign Service Association. Colin Powell, secretary of state at the time, said Bingham “risked his life and his career” to help 2,500 Jews and others on “Nazi death lists” leave France for America and “do that which he knew was right.”

Correction: This story has been corrected to show that Bingham was one of two Americans on the list instead of the only one. Sousa Mendes’ consulate location was also corrected; he was stationed in Bordeaux, not Marseille.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO