Kandinsky painting returned to Jewish family as Netherlands shifts approach to looted art

The decision reverses a 2018 ruling against the descendants of Johanna Margarethe Stern-Lippmann, who died in Auschwitz

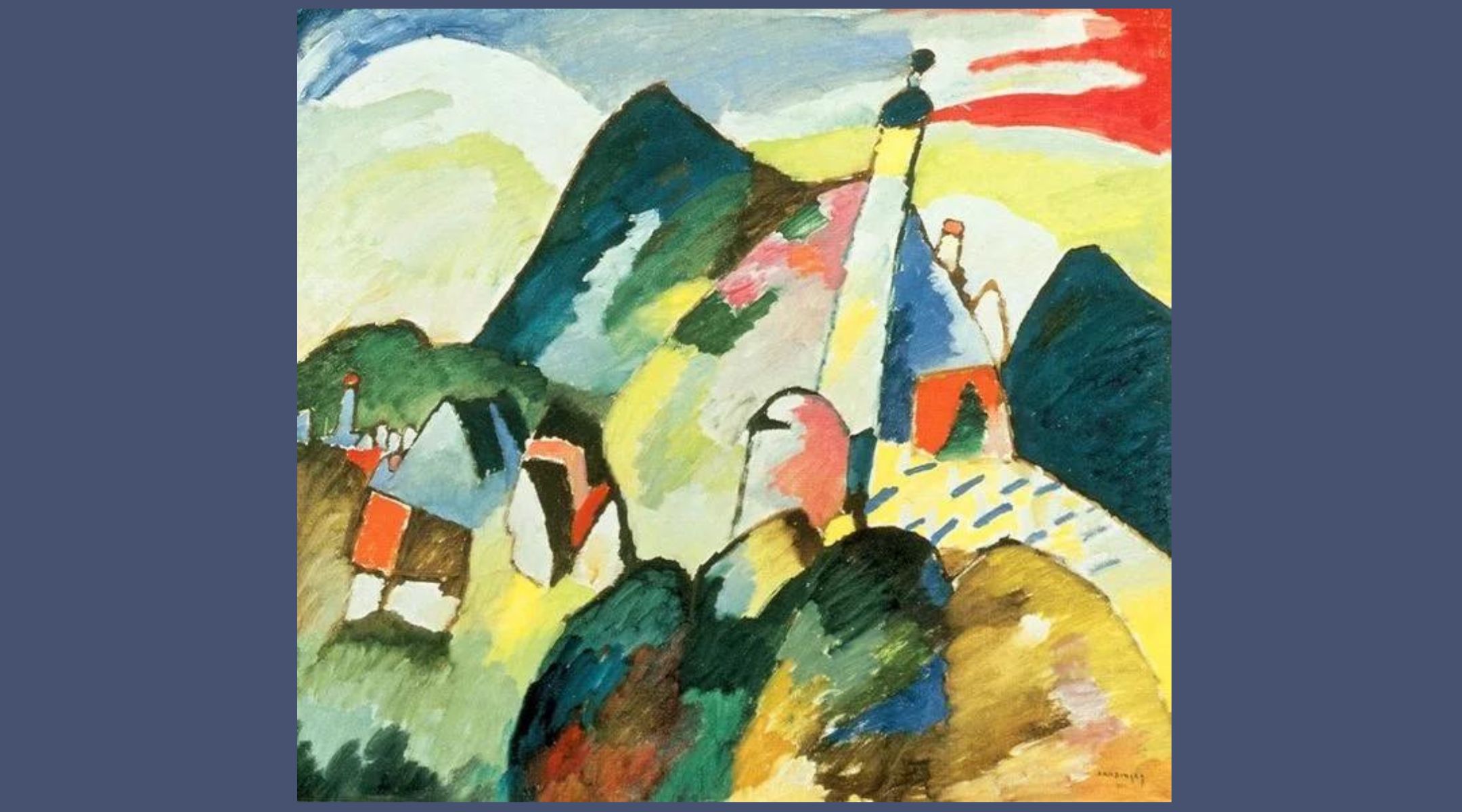

In September 2022, the Wassily Kandinsky painting “View of Murnau with Church” was returned to the descendants of a Jewish art collector who was murdered in the Holocaust. (Public domain)

(JTA) — A Dutch committee charged with assessing and acting on claims about artwork stolen from Jews before and during the Holocaust has determined that a painting by Wassily Kandinsky should be returned to the family of the Jewish woman who likely owned it prior to the Holocaust.

The family of Johanna Margarethe Stern-Lippmann, who was murdered in 1944 at Auschwitz, should regain possession of “Blick auf Murnau mit Kirche,” or “View of Murnau with Church,” an abstract work that the Dutch city of Eindhoven has owned since 1951 and has displayed at its art museum, according to the Dutch Restitutions Committee.

The decision reverses an earlier one, in 2018, in which the committee determined that there was not enough evidence to show that Stern-Lippmann had possessed the painting after the Nazis assumed power to prove that she had given up ownership under duress.

Earlier this month, the committee ruled that new evidence had emerged to support the family’s claim to the painting. Because Stern-Lippmann, a prominent art collector and trader before the Holocaust, was Jewish, without any evidence that she had sold the painting voluntarily prior to the Nazi invasion, it was appropriate to assume that “View of Murnau with Church” had been expropriated during it, the committee concluded.

“We are thrilled that the Kandinsky has been returned to us,” descendants of Stern-Lippmann in Belgium, the Netherlands and the United States said in a statement. The family, which has previously had works restored to it by France, had protested against the committee’s 2018 decision.

“The painting used to have a prominent position hanging in our (great) grand-parents’ house and represents much of our family’s story,” the family members said. “Its coming back to us now marks an important moment. It won’t bring back the nine immediate family members who were so tragically murdered, but it’s an acknowledgment of the injustice that we, and so many like us, have endured.”

The return of the painting is the latest in a string of decisions in the Netherlands in favor of the descendants of Jews who lost precious art during the Nazi regime. A famous marine painting was removed from the halls of the Dutch parliament in May pending an ownership claim, while the Stedelijk Museum earlier this year restored possession of one of its Kandinsky paintings to the family of the Jewish woman who said she owned it prior to the Holocaust.

The question of how to handle artwork with ownership claims by the families of Jews persecuted by, and in many cases murdered by, the Nazis has long vexed the art world and legal authorities.A 1998 conference brokered by the United States sought to achieve consensus on how to handle looted art; at the time, the conference’s organizer, U.S. Undersecretary of State Stuart Eizenstadt said France possessed 2,000 looted works and had returned only three.

The Netherlands — where in 1940 the invading Germans and their collaborators found many Jews who had fled Nazi Germany years earlier — had already formed its first restitution committee in 1997, but it adopted the principles laid out during the Washington Conference when it convened the Advisory Committee on the Assessment of Restitution Applications in 2001.

The committee has made about 170 recommendations, most of them binding rulings, pertaining to some 1,500 items. Among the binding rulings, 84 were fully or partially in the applicants’ favor and 56 were to reject the claim in full.

Over time, the Netherlands’ once-strong reputation in returning looted art has suffered because of the Dutch judiciary’s unique approach of balancing the interests of heirs with those of museums interested in displaying important works of art that happened to be stolen by the Nazis.

The “weighted interest” approach has drawn criticism in a country where widespread collaboration was a key reason for the highest death rate achieved by the Nazis in occupied Western Europe. Several prominent collections that were widely understood to have been looted from Jews remained in the possession of Dutch museums as a result of the approach.

In December 2020, the committee announced a “recalibration and intensification” of its efforts to provide justice in matters related to looted art, including conducting systematic research into the wartime history of artworks, and especially ones in the possession of museums and public institutions.

The four rulings announced since then have all been in favor of Jewish families seeking to reclaim possession.

“View of Murnau with Church” is the latest and most significant among them. Painted by the famed Russian-French abstract artist Wassily Kandinsky, it was a centerpiece of the collection at the Eindhoven Museum, beginning when the museum acquired it in 1951 from a trader known to have trafficked in looted art. The picture is no longer visible on the museum’s website, although descriptions of several exhibits that featured it still are.

Exactly how many pieces of artwork were looted in the Netherlands and beyond remains unclear. Luckier Jewish families sold valuable art at a pittance to generate funds to flee the Nazis, or left their works behind while escaping. Other families lost their art as Jewish families were stripped of their belongings, then murdered. About 80% of Dutch Jews, many of them wealthy Germans who had fled the Nazis there, were killed during the Holocaust.

The Restitutions Committee is not the only effort underway in the Netherlands to determine the provenance of possibly looted art. A task force investigating the origins of the 3,500 pieces of art owned by the Dutch government has flagged some works as requiring investigation.

In one notable case, the task force called attention to “Fishing Boat Near the Shore” by Hendrik Willem Mesdag, a well known marine painter, which long hung in the Dutch parliament as a reminder of the Netherlands’ complex relationship with water.

But the 1891 painting of ships braving high winds was removed last spring from the walls of the Eerste Kamer, the upper house of the Dutch parliament, pending an investigation into its provenance, the Omroep West broadcaster reported in May.

The speaker of the House of Representatives, Vera Bergkamp, said the investigation was a “moral duty” and that, after obtaining information suggesting it had been stolen from a Jewish family, she had decided to have the painting put into storage pending the result of the probe.

The voluntary removal represents a powerful symbol of the shifting tides related to the repatriation of art with public value. In March, the Stedelijk Museum, a municipal institution of the City of Amsterdam, finally returned one painting that had been looted but that a judge said can remain in the possession of the museum as per the weighted approach.

The work, “Painting with Houses” also by Kandinsky, had become a symbol for the perceived injustice of the weighted approach, which acknowledged the theft but denied the rightful owners possession of what their family had lost.

The Stedelijk, acting on the order of the mayor’s office, returned it following a protracted legal fight to descendants of the late Holocaust survivor Irma Klein. Her family had sold the painting directly to the Stedelijk during the Nazi era under duress for the equivalent of $1,600. It is now believed to be worth an eight-figure sum.

While it was by far the most well-known case of looted art on display in the public domain in the Netherlands, it is hardly the only one. According to RTL, provenance checks are underway with regard to additional works in parliament and in museums across the Netherlands.

The repatriation of looted works is continuing in other European countries where large swaths of artwork may have been stolen from Jewish collectors before and during the Holocaust. In Germany, in a move unrelated to the investigations in the Netherlands, three museums in July returned five paintings to heirs of Carl Heumann, a Jewish banker and art collector from Cologne who did not survive World War II, the Br23 news site reported.

This article originally appeared on JTA.org.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO