For ‘Ragtime’ star Brandon Uranowitz, to be Jewish is to be hopeful

The Tony Award-winning actor plays a plucky Jewish immigrant in a timely revival

Brandon Uranowitz stars as Tateh in the New York City Center’s production of Ragtime. Photo-illustration by Canva / images courtesy of Jenny Anderson

“America is one giant Shtetl, where I swear life is great,” a man sings in Yiddish as he and his young daughter approach Ellis Island: “A shtetl iz amerike / A mekhaye, khlebn.”

These are lyrics from a Yiddish theater folk song as they appear in the 1998 musical Ragtime. Latvian Jewish immigrant Tateh and his daughter promise each other that America will be a land free from bloodshed and cruel autocrats. A chorus of Italian and Haitian immigrants join the song in their own languages, as the group makes their way to the Lower East Side.

In the latest revival of Ragtime, opening at the New York City Center tomorrow, Brandon Uranowitz plays Tateh, a widowed Jewish businessman yearning for success in “Amerike.”

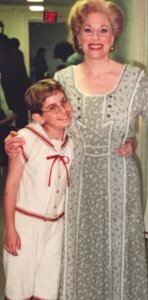

Uranowitz was performing in Ragtime before he was even a bar mitzvah. As a preteen, he acted in the original Toronto production of Ragtime before it transferred to Broadway. While he turned down an offer to be an understudy on Broadway, Uranowitz said that Ragtime opened his eyes at a young age to how theater can tell sweeping, powerful stories.

Since then, Uranowitz has built a formidable career playing complex Jewish roles on stage and screen. He played Adam Hochberg in American in Paris and therapist Mendel Weisenbachfeld in the 2016 revival of Falsettos. In 2023, he won a Tony Award for his dual roles in the epic family drama Leopoldstadt.

Ragtime is returning at a fraught moment in American politics. The play’s themes of xenophobia and factionalism feel especially pointed with a national election just one week away.

I spoke to the Tony-winning actor about playing Jewish characters on stage, and what it means to return to Ragtime as an adult, and in today’s discordant United States.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

SAMUEL ELI SHEPHERD: One thing I really love and appreciate about your career is how you’ve so often played explicitly Jewish roles on stage. Was it always your intention to play Jewish roles, or was that something you fell into?

BRANDON URANOWITZ: No, it’s something I fell into.

I did have a very complicated relationship with my Jewish identity, specifically where it intersects with my gay identity. I grew up going to a Conservative synagogue in New Jersey. There could have been gay members of the shul, but they weren’t out and I didn’t know about them, so I didn’t feel particularly welcomed there.

Fast forward many years later when I graduated school thinking that I would get to play whatever I wanted, it became very clear very quickly that unless Jewish was in the character breakdown, I wasn’t going to be playing it. That further complicated my relationship with that identity because I resented the fact that I was confined to this one thing.

SHEPHERD: When did you stop resenting it?

URANOWITZ: It sort of cracked wide open when I got to do Leopoldstadt and tell my family’s story, that I finally understood what my purpose was as an artist. That my purpose as an artist was not just for me. It’s for other people out there who look like me and grew up like me and are like me. That’s my responsibility.

Once I removed the ego from the equation, I really started to examine and interrogate and investigate what being Jewish really means to me.

I think, especially because I grew up going to a Conservative synagogue, that Judaism and Jewish identity was intrinsically tied to a belief in God, and the practice of prayer and the Siddur and the Torah and all of those things.

I realized that that’s not actually what being Jewish has to be. Being Jewish can mean so many different things for so many different people. And for me, it’s about family and values and acceptance.

This [Ragtime] feels like it’s coming at exactly the right moment in my life. It would not have been right for me to step into this man’s shoes had I not gone through that journey with my identity. And I can now really live inside this person’s head and this person’s being without an ego.

SHEPHERD: You mentioned when you were doing Leopoldstadt last year about the satisfaction of being in a production in which you saw your own family history being represented onstage.

Ragtime is of course a very different story than Leopoldsdadt, and it speaks of Jewish identity and immigration in an entirely different historical context. Still, do you see any of your own family history represented in Tateh?

URANOWITZ: I mean, he immigrated here before World War I, and my family immigrated here during World War II. But that optimism, that hope, there is a connection between the two. I think that hope and optimism is at the root of our survival as a people. I mean, I’m only here today because of my family’s hope and optimism in the face of terror and horror and violence.

I think that optimism is not unique to Tateh in any way. I think it’s in our DNA.

SHEPHERD: I recently learned that Tateh is Yiddish slang for the word, “father.” There’s also some Yiddish in the show. Do you have any connection to the Yiddish language?

URANOWITZ: My dad knows a lot of Yiddish. My great aunt, who I knew very well, was one of the only Holocaust survivors that I knew. She mostly spoke Yiddish. She read Yiddish newspapers. She read Yiddish books. And so I heard it in the house a lot.

My family is also the product of the post-World War II Jewish effort of assimilation. I do think in an effort to assimilate, Yiddish wasn’t a huge part of growing up. I heard it growing up, but there wasn’t an effort to teach me.

SHEPHERD: Would you ever try to learn it now?

URANOWITZ: While I am not necessarily devoted to learning myself, I believe very deeply it would be tragic to lose it. It would be like Italians losing their ways of making pasta by hand, you know? I believe in the continuation and celebration of the old world.

SHEPHERD: Ragtime ends – spoiler alert – with Tateh marrying the character “Mother,” who is a U.S.-born, white Anglo-Saxon Protestant. The two hit it off after their children became friends. Tateh works his way up from being a Lower East Side merchant of illustrations to becoming a successful filmmaker in California.

In your Tony Award speech last year, you mentioned how Leopoldsdadt warns about the “false promise” of assimilation. I have to ask, do you think Ragtime sends a pro-assimilation message with this ending?

URANOWITZ: Our incredible director Lear deBessonet talks about Ragtime being about “the promise and the wound of America.” I think Ragtime is unique in that it’s able to hold the need for a melting pot and the need for insulation within your own cultural group.

Also, I don’t know if they were necessarily totally aware of this when they wrote it, but it’s an interesting view into whiteness and proximity to whiteness and Ashkenazi Jewish proximity to whiteness. Tateh assimilates, because he’s a Jew. Coalhouse and Sarah [both Black characters] don’t have that privilege.

There is that question — is assimilation a worthy endeavor? Because assimilation is just moving to the more dominant culture, and there are some people who can never do that. I struggle with the idea of assimilation and the idea of sacrificing your own “culturalisms” for the sake of integration.

SHEPHERD: How does being in Ragtime now feel different from the play you performed as a kid – both in terms of how you have changed and also how the world around you has changed?

URANOWITZ: Young Brandon’s experience of the show was so childlike. There was just curiosity and wonder. I like to think that I move through my life still with curiosity and wonder, but I also move through it with cynicism. I move through it questioning everything around me. I move through it with my own political values and ideals and principles.

And as Adult Brandon, I’m just kind of struck that a piece written when I was an actual child still is so unbelievably prescient. This version specifically, with this cast, with this director and choreographer and music director, especially within the middle of one of the most consequential elections happening in our lifetime.

It just feels huge and massive and important and extraordinary and exciting and scary and all of the things. I feel deeply privileged and honored to be telling this story right now.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO