How George Harrison, the Beatles’ unsung hero, wrote his own ‘Hallelujah’

Author Seth Rogovoy thinks Harrison is an ‘underdog’ who deserves more credit

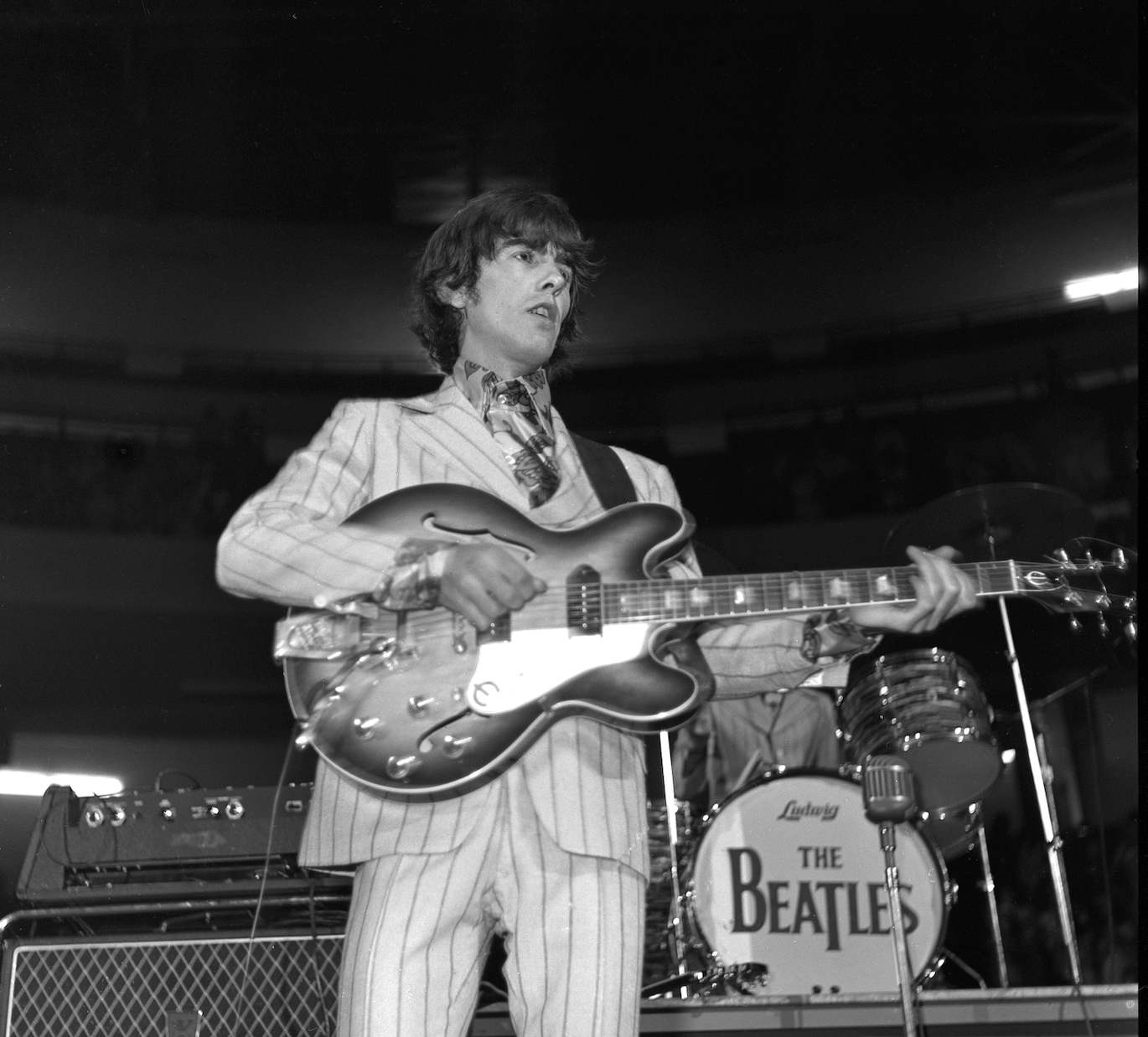

George Harrison playing Olympia Stadium in Detroit in 1966. Photo by Douglas Elbinger/Getty Images

If there is a “Jewish Beatle,” it’s probably the one who was spotted at Yom Kippur services this month.

But though Paul McCartney married into the faith multiple times and was once rumored to have considered converting, he also has a song about heeding words of wisdom coming from mother Mary, which many listeners take to mean either his own mother, named Mary, or that of Jesus.

Only one bandmate responded to Beatlemania with a kvetch.

“When John and Paul were still writing songs about, you know, puppy love and teenage love, and ‘I Saw Her Standing There,’ and ‘Can’t Buy Me Love,’ George was writing a song called, ‘Don’t Bother Me,’” said Seth Rogovoy, contributing editor to the Forward and author of Within You Without You: Listening to George Harrison.

In the book, Rogovoy takes a closer look at Harrison’s contribution to the Beatles and as a solo artist, going song by song and record by record. The book takes on the iconic — and nearly undecipherable — chord that opens “A Hard Day’s Night” and situates the lead guitarist’s musical evolution within his spiritual development.

Harrison, whose tenure with the Beatles was often colored with a kind of reluctance, is, for Rogovoy, the ultimate underdog, with contributions that are undersung both in terms of the band’s discography and for popular music as a whole. Though Harrison is often called the quiet or the spiritual Beatle, Rogovoy’s survey goes beyond that label, positioning Harrison as the most narratively inventive of the quartet, and, perhaps, the one responsible for much of what we consider the group’s sound. (And, in this age of streaming he never lived to see, it’s two George songs, “Here Comes the Sun,” followed by “Something,” that are the most streamed songs in the Beatles catalog.)

I spoke with Rogovoy, also the author of Bob Dylan: Prophet, Mystic, Poet, about Harrison’s music, his Dylan connection and how Harrison fused two religious traditions together in a chart-topping hit. The following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Why George?

George was always my favorite Beatle. They’re all incredibly talented, fascinating in their own right, but I was just drawn to George, partly because he’s the underdog. And I guess I’m always drawn to the underdog — I’ve been a lifelong New York Mets fan. About 10 or 12 years ago, I really started listening to the Beatles with new ears. What really jumps out at me is George. His songs themselves, to me, have a qualitative difference — they started out maybe sounding like Beatles songs to some extent — but even from the very beginning, there was something different about the way he wrote and about the things he wrote about.

You sort of give Harrison the credit of co-creating folk rock with Bob Dylan. Obviously he’s the Beatle who collaborated the most with Dylan. I’m wondering what you, as a Dylan expert, make of there being such an affinity there.

George was an instant fanboy, as early as Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan in ’63. He brought it to the others and they were all blown away. Bob Dylan just showed this whole other level of what you could do with rock lyrics and how you could intersperse a style of poetry and talk about serious things. Nobody had ever really tried that. George really glommed onto that, and it affected his songwriting right away.

There was a famous kind of couple of weeks, I believe it was November, around Thanksgiving time, 1968 where George Harrison went to Woodstock and hung out with both Bob Dylan and the Band. He wound up writing some songs with Dylan and they’re a beautiful fusion of Dylan’s poetry and George’s weird chords, which is what Dylan wanted it to be.

When the Beatles are over, and each one of them is putting out a solo album, which is kind of a statement of who they are on their own, George’s was All Things Must Pass. The very first song you hear on that album is a song he co-wrote with Bob Dylan, “I’d Have You Anytime.” The album also included George’s version of a brand new Bob Dylan song at the time called “If Not For You.”

George lured Bob Dylan out of seclusion. The Beatles and Bob Dylan both coincidentally quit touring and live performing in the year 1966, so when it came time for George to put together the 1971 benefit concert for the humanitarian crisis in Bangladesh, George turned to his friend, Bob Dylan, who certainly you would think would have wanted to make his public comeback on his own terms. But in fact, they were close enough, and Dylan cared enough about George, to present himself back in the world, and be subsumed by this other event that was really a George Harrison event. The whole concert led up to Dylan and if you watch the film footage, it’s just a beautiful statement of friendship.

They collaborated at different times, most famously after that, of course, in the late ’80s and in the early ’90s, with The Traveling Wilburys, where they actually formed a band, where you got one Beatle and Bob Dylan and some other huge rock stars. Nobody would have ever expected that. And it was a way for them just to have fun. Dylan always kind of envied people being in a band, and George Harrison always envied people being in a band of people he liked!

This is your least Jewish book, it’s safe to say, but “My Sweet Lord” gave us a popular music hallelujah before Leonard Cohen did. What does the song tell us about Harrison’s music and spirituality?

Obviously “hallelujah” is in common parlance. Most people don’t think of it in terms of either Judaism or even being Hebrew. But in fact, it is a Hebrew word, and it does originate in Jewish scripture and liturgy. And so it’s just amazing to think that this huge global, English language hit which crossed all cultures and borders has a refrain, and this is a pop tune, that is one part literally in Hebrew, and the other part in Sanskrit. I don’t think George necessarily sat down and thought, “Oh, I’m going to put Hebrew next to Sanskrit” — hallelujah and Hare Krishna and Hare Rama. They all work together as words.

“Within You Without You” — of all the songs why did you pick that one for a title?

“Within You, Without You” has several different meanings and overtones. Within the Beatles and outside of the Beatles is one of the places my mind goes. The song itself was one of his greatest realizations of writing about philosophy and spirituality in song, and in particular, in a fusion of northern Indian or Hindustani classical music fused with pop music or rock music.

This is kind of the quintessential raga rock to me. It really stands as a symbol of George’s breaking down walls and borders in terms of culture, in terms of spirituality, in terms of religion, and most importantly — and what really led into all this — in terms of music. Philip Glass credits George Harrison with fomenting the entire notion of what we now call “world music.” To have a Beatle, one of the world’s foremost famous pop musicians, tackle that project of using eastern and Western music was so influential, in popular music and in the greater culture.

There are some misconceptions that you’re hoping to correct here. For example, the idea that George is a lesser guitarist or was kind of a lesser Beatle.

The culture has created this notion that being a great guitarist means one thing, and it means being able to either play really fast and or “shred” is what they call it these days, basically improvising on blues chords, which is one thing you can do with an electric guitar, and it is one thing that a lot of rock guitarists do. People like Eric Clapton, that’s what they do.

George’s approach was not about improvisation; it was about composition.

Let’s say they introduced a song one afternoon in the studio. And it’s like, “OK, George, these eight bars, you should do an instrumental here.” George didn’t just immediately stand there and do an eight bar blues improvisation. George took this and said, “Let me take this home tonight,” and he stays up all night and he comes back the next day with a perfectly written and executed musical interlude or intro, or he found a way to end a song on an unusual chord. All these little things musically that make Beatles recordings so distinctive. People think, “Well, you know, he wasn’t Jimi Hendrix, he wasn’t Eric Clapton!” Well, that’s apples and bananas. That was never his point.

I’m tempted to ask you if you have a favorite song, but then maybe the better question is, if there’s a song that people should revisit, or that you feel is underappreciated, and maybe it’s the same answer.

Probably the song that I go back to over and over again is the song “If I Needed Someone,” which was on the Rubber Soul album. It’s one of the ones that really introduced that kind of 12-string electric guitar, resonant jangle sound that’s so associated with mid-’60s Beatles.

And the sophistication of his narrative approach. He chose a way to write us a love song — or a not love song, because you can make the case for it being one and or the other or neither. But how many rock singer-songwriters would write a song in the conditional tense? Just the title alone, “If I Needed Someone.” And so the song goes through this litany of “if this, if that, then I might.” You see this cropping up throughout a number of different George Harrison songs, like “Something.” “You’re asking me, will my love grow? I don’t know. I don’t know.” Well, if you don’t know, who should we ask?

What I love about that song is how George is just starting to listen to Indian music. There’s no sitar on that song, but you still hear certain kinds of Indian sonorities sneaking into his writing in terms of the whole first, long line, which is really kind of a raga or a drone note, and how he chooses to sing along with it.

It’s fun as somebody who really listens closely to music, and tries to figure out what people are doing, and how they’re doing it, to discover these things and to say, “Oh, that’s why this song is so appealing.” There’s a few others, obviously — they come and go — but that could stand for the favorite.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO