How a Jewish kid named Lou Reed left ‘the most boring place on earth’ to become ‘King of New York’

The career of the legendary founder of the Velvet Underground was filled with Jewish references and collaborators

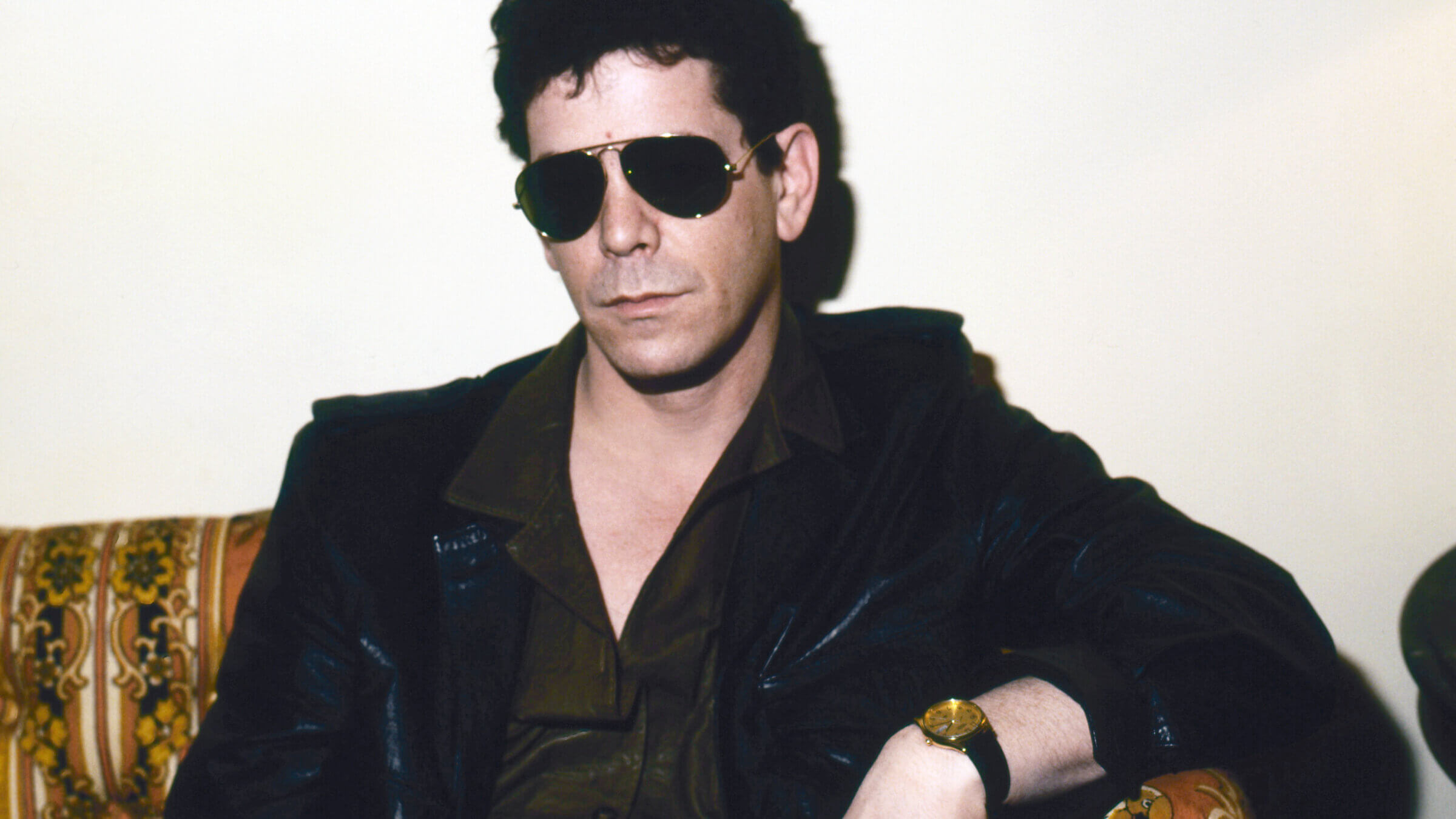

Lou Reed in London, 1982. Photo by Getty Images

Lou Reed: The King of New York

By Will Hermes

Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 560 pages, $35

Anyone with more than a cursory knowledge of the late Lou Reed’s life and work knows that the legendary rock ‘n’ roll poet was Jewish and that Jewish themes and references occasionally surfaced in his songs. But a close reading of the recent, magnificent biography Lou Reed: The King of New York by Will Hermes portrays the rock songwriter — a cofounder of the hugely influential group the Velvet Underground who went on to enjoy decades of acclaim as a solo artist — as more deeply rooted in Jewishness and Jewish culture than the average fan might have realized.

From his early work with the Velvet Underground through his solo career, especially in later years, when he took on targets including U.N. Secretary General Kurt Waldheim for his Nazi past and Louis Farrakhan for his overt Jew-hatred, Reed’s Jewish identity was never far from the surface. And while he was never thought of as a Jewish rock-poet in the manner of Leonard Cohen and Bob Dylan, he was reminded of his status as a member of the tribe at times, including when an antisemitic mob shut down one of his concerts in Italy in 1974.

Reed was also drawn to a series of mentors throughout his life, most of them Jewish, including the poet Delmore Schwartz and the early-rock songwriter Doc Pomus, to both of whom he paid tribute in song on several occasions. Andy Warhol was one of the few influential figures in his life who was not Jewish, but Warhol’s role as a mentor to Reed via his championing of the Velvet Underground — who became the unofficial “house band” of The Factory, Warhol’s studio headquarters, and the group’s central role in happenings including the Exploding Plastic Inevitable — comes up for serious questioning in Hermes’ meticulously researched book. Warhol was as much or more a collector of talent — sometimes to the point of intrusiveness (as when he imposed the German vocalist Nico on the Velvet Underground) — as he was a wise man or father figure. (Not to minimize Warhol’s importance to Reed and company; Reed and Velvet Underground cofounder John Cale joined forces to pay tribute to their one-time “manager” on the critically acclaimed 1990 album, Songs for Drella.)

In addition to his beloved doo-wop music, r & b, and early rock ‘n’ roll, Reed’s creative influences included a minyan of Jewish artists, including the aforementioned Dylan and Doc Pomus, plus Norman Mailer, Lenny Bruce, Leonard Cohen and Allen Ginsberg.

A wandering Jew

Lewis Allan Reed was born in March 1942 at Beth-El Hospital in Brooklyn to Toby (née Futterman) — the child of Jewish immigrants — and Sidney Joseph Reed, a certified public accountant. Beth-El was a voluntary nonprofit developed by the area’s then-sizable Jewish community. Père Reed was born Rabinowitz, but at some point he realized, like many of his generation, that a less obviously Jewish name might smooth over some friction with his business and social connections. Sid’s two brothers likewise changed their names to Reed.

Like many of his generation, Sidney Reed — the child of Russian-Jewish immigrants, born in 1913 -— moved his family out of Brooklyn to Long Island, landing them in the suburb of Freeport, a seaside town on Long Island’s South Shore. After five years of living in an apartment in Sheepshead Bay, this was a huge transition for all, including Reed’s younger sister, Merrill. Upon arriving in Freeport, the Reeds joined the conservative Congregation B’nai Israel, where they attended services and where 13-year-old Lewis became bar mitzvah.

As Hermes describes, Freeport was once an oystering village that turned into a resort town and artists’ colony. It became a magnet for the New York theater and vaudeville crowd; the likes of Sophie Tucker, Irving Berlin, and Al Jolson — all Jews — stationed themselves there alongside more mainstream neighbors including Will Rogers and John Philip Sousa. By the time the Reeds moved to Freeport, however, the village that young Lewis would later describe as “the most boring place on earth” had lost its bohemian allure; its most famous musician by then was “the middlebrow schmaltz king” Guy Lombardo, best known for his annual New Year’s Eve rendition of “Auld Lang Syne.”

Freeport did, however, boast a rock ‘n’ roll radio station, WGBB, which Reed listened to religiously. Reed began haunting a downtown record shop, buying singles by Fats Domino, Hank Ballard, the El Dorados, and the Cadillacs. Reed found some likeminded friends and formed a band. As Hermes writes, “[T]hey hit on an unsurprising idea for the annual school variety show: a Little Richard act. (It’s difficult to overstate the impact the groundbreaking musician had at the time; in Minnesota the previous year, a young Jewish man named Robert Zimmerman had a similar notion, and gave a Little Richard-style performance at the Hibbing High School variety show.)” The stage was set, and after a somewhat tormented adolescence that saw Reed being incessantly bullied and experiencing what we now know were panic attacks, Reed was almost single-minded in his pursuit of rock ‘n’ roll fame.

Not that there weren’t detours along the way. He briefly attended New York University (whose main campus was in the Bronx at the time); by the spring of his first year he withdrew from the school due to an emotional breakdown. Reed was diagnosed as schizophrenic and was treated with electroconvulsive therapy. Upon recovery, such as it was, Reed attended Syracuse University, where he first met Delmore Schwartz. It was there that he also met Sterling Morrison, another acolyte of Schwartz’s and an aspiring guitar player who would eventually join Reed in forming the Velvet Underground. A few years later, Reed paid tribute to Schwartz in song, including the angry “European Son” by the Velvet Underground and the very beautiful “My House.” The latter kicks off his landmark 1982 album, The Blue Mask, where Reed sings, “My friend and teacher occupies a spare room / He’s dead, at peace at last the wandering Jew.”

After graduating from Syracuse, Reed moved back home to his parents’ house. He scored a job as a staff writer at Pickwick Records. “Like thousands of his suburban neighbors, the newly minted college graduate rode the LIRR from Freeport Station to Penn Station,” writes Hermes. Pickwick was a cut-rate version of the Brill Building, a song factory where writers were given the equivalent of assembly line tasks: write ten California songs, write ten Detroit songs, etc. It was a good training ground for an aspiring songwriter, and it also gave Reed a chance in the studio, recording demo tracks of the songs he wrote, including a minor hit called “The Ostrich,” an attempt to cash in on the novelty dance craze. Out of this work was born Reed’s first real band, the Primitives, who would eventually morph into the Velvet Underground.

Around this time, Reed met filmmaker Barbara Rubin, who knew Bob Dylan and who introduced Reed to Andy Warhol. The story about how the Velvet Underground became the “house band” at Warhol’s Factory is well known; what might come as news to some is that Reed and Nico, whom Warhol installed as a vocalist with the band, had a brief affair that did not end well. As Hermes recounts, Nico believed Reed had a grudge against her because of her German heritage, “what my people did to his people.” When one day she arrived late for rehearsal, she was “met by a very chilly Reed,” writes Hermes. “After a stretch of silence, Nico announced ‘I cannot make love to Jews anymore.’”

Nico was, however, responsible for introducing two future titans of rock poetry. “As it happened,” writes Hermes, “another Jewish singer-songwriter/poet/fiction writer, Leonard Cohen, met Nico … around this time…. Nico introduced Cohen to Reed, who was familiar with his writing. ‘[He] surprised me greatly because he had a book of my poems,’ Cohen recalled. ‘I hadn’t been published in America, and I had a very small audience even in Canada. So when Lou asked me to sign Flowers for Hitler [a poetry collection], I thought it was an extremely friendly gesture of his.’” Hermes also recounts a little-known meeting between Reed and the Beatles’ Jewish manager, Brian Epstein, who was sniffing around for other groups to manage once the Beatles stopped touring. Epstein’s death from a drug overdose in 1967 rendered that possible arrangement moot.

The Velvet Underground struggled to gain traction outside of a very small but fanatically loyal following, first in New York City and then, curiously, in Boston. After ruling the roost at Manhattan’s Max’s Kansas City nightclub, the band found an out-of-town headquarters at the Boston Tea Party, a Fillmore-like venue near Fenway Park located in what once had been a Unitarian meeting house in the late 19th century. A significant feature of the building’s design was a large window with a Star of David carved into it, earning the place the nickname “the old synagogue.”

Still, the band never caught on in any big way. It would be via its influential legacy that the group would eventually be thought of as one of the most important rock groups of all time, encapsulated in the famous Brian Eno quote that only 30,000 people bought the first Velvet Underground record, but each one of them started a band.

By 1970, Reed had had enough, and he moved back in with his parents in Freeport and worked part-time as a typist for his father’s accounting firm. Joining him at home was his then-girlfriend and soon-to-be first wife Bettye Kronstad, who slept on a fold-out couch in the den; “on Sunday, they’d all have brunch with bagels and whitefish,” writes Hermes.

Songs filled with Jewish themes and references

It wasn’t long, however, before Reed began writing songs and launching a new career as a solo act. His breakthrough album, 1972’s Transformer, was produced by rising star David Bowie, and spawned several hits, including “Walk on the Wild Side” and “Satellite of Love.” The album title also hinted at one of the album’s main themes, as well as one of Reed’s personal obsessions. While many or most may not have realized it, the “trans” in “transformer” referred to various real-life transgender friends and acquaintances, including the “Walk on the Wild Side” characters “Holly” (Holly Woodlawn) and “Candy” (Candy Darling). If Hermes’ authoritative and sensitive biography has an overarching theme, it is the underappreciated gender fluidity in Reed’s personal life as well as in his songs.

With the success of Transformer, Reed’s solo career was on solid footing, and he issued a steady stream of albums over the next few decades and often toured. While he was especially beloved in Europe, this did not mean he always had an easy go of it. In Italy in 1974, his arrival in Milan provoked violent protests: flyers accused Reed’s Jewish promoter, David Zard, of being a “torturer in the Moshe Dayan forces,” and, according to Hermes, “two songs into his set … rioters in masks stormed the stage with clubs and shut it down, trashing equipment and instruments, tearing out seats, hurling stones, bolts, bottles, and petrol cans, and shouting anti-Semitic slurs.”

When Reed was dropped by RCA in 1976, Clive Davis stepped in and signed Reed to his nascent label, Arista. Hermes quotes Davis thusly: “[H]e would come to my house to watch the Thanksgiving Parade float down Central Park West, and nosh on bagels and appetizers – just a Jewish guy who grew up in Freeport.” Reed’s 1978 album, Street Hassle, featured guest appearances by Bruce Springsteen and Genya Ravan, the latter born in Łódź, Poland to a Jewish family in 1940, and who fronted Goldie and the Gingerbreads, one of the first all-women rock bands. Most of Ravan’s relatives perished in the Holocaust.

Along the way, Reed peppered his songs with Jewish themes and references. The narrator of the Street Hassle number “I Wanna Be Black” — one of Reed’s more provocative tunes, influenced by Norman Mailer’s essay “The White Negro” — sang “I wanna be black, have natural rhythm …. And fuck up the Jews.” The opening lines to “Fly Into the Sun,” on 1984’s New Sensations, are “I would not run from the Holocaust / I would not run from the bomb.” By the time Reed’s critically acclaimed New York album came out in 1989, he was inveigling against former UN secretary-general and recently installed Austrian president Kurt Waldheim, who had successfully hidden the fact that he was a Nazi intelligence officer during World War II, in the song “Good Evening Mr. Waldheim.” The same song also targeted Reverend Jesse Jackson for his support of the PLO, for his defense of Louis Farrakhan, who espoused openly antisemitic views, and for Jackson’s reference to New York City as “Hymietown.” The same album also featured the song “Busload of Faith,” which asserted “You can’t depend on the goodly hearted / the goodly hearted made lampshades and soap.” Other songs on New York targeted soon-to-be New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani and renowned playboy Donald Trump.

Reed maintained his friendship and tutelage with Doc Pomus until the hit songwriter died in 1991. Born Jerome Solon Felder in Brooklyn in 1925, Pomus was responsible for hits including “A Teenager in Love,” “Save the Last Dance for Me,” and “This Magic Moment.” Pomus was Reed’s inspiration for many of the songs focused on mortality on his 1992 album, Magic and Loss. Reed spoke at Pomus’ funeral, reflecting on “how great Pomus was to talk to … how Pomus always cheered him up, and how they’d had plans to go to Katz’s Deli so Reed could try the grilled beef knoblewurst, which Pomus insisted would change his life,” writes Hermes. Worship of Pomus by a younger generation of songwriters extended to Reed’s contemporary, Bob Dylan, who dedicated his 2022 book, The Philosophy of Modern Song, to the much-lauded songwriter.

In what seems like an odd pairing from the get-go, the echt-urbanite Reed — David Bowie bestowed upon him the title “The King of New York,” thus providing the biography’s subtitle — appeared at the annual Farm Aid superstar benefit concert three times. In his case, the third time – in April 1990 — was not the charm. Rather, it proved to be his last waltz with the Farm Aid organization, originally launched after an idle comment by Bob Dylan at the Live Aid concert in which the future Nobel Prize-winner said he hoped some money could be put aside for America’s downtrodden family farmers. Reed was “outraged” by the inclusion of Guns N’ Roses in the lineup, whose controversial song “One in a Million” included lyrics with racist and homophobic slurs. Hermes writes, “Reed found [John] Mellencamp, a friend from earlier Farm Aid events, in his dressing room. ‘He was worked up about it,’ said Mellencamp, who implied the author of ‘Heroin’ was a hypocrite. Reed played the concert, but he and Mellencamp never spoke again.”

One of the most surprising friendships Hermes reveals was the one between Reed and John Zorn, an avant-garde saxophonist and composer who was a fixture of New York City’s downtown music scene since the late 1970s. As a precocious youth, Zorn had snuck into a Velvet Underground concert at age 12 in 1965. Among Zorn’s various projects was finding ways to incorporate Jewish themes and modalities into his music, which led to the formation of his Masada quartet and book of compositions numbering in the hundreds. Zorn curated a two-day program at the 1992 Munich Art Projekt called “The Festival for Radical New Jewish Culture,” which in its shortened term, Radical Jewish Culture, lent its name to an entire movement of Jewish and non-Jewish composers and musicians (including Frank London, Gary Lucas, Marc Ribot, and Jon Madof) exploring various aspects of Jewish heritage, mysticism, and theology through highly personal musical approaches, many of whom released recordings on the Radical Jewish Culture imprint of Zorn’s Tzadik record label. Zorn reached out to Reed and invited him to join the festival in Munich.

I knew that Reed and Zorn had worked together, having seen them perform as an experimental trio with Laurie Anderson aka Mrs. Lou Reed at the Montreal International Jazz Festival in 2010. What I didn’t know until reading Hermes’ book is that Zorn played matchmaker to Reed and Anderson back in 1992, introducing the two at JFK Airport while they were all waiting to fly to the Munich festival. “In a jazz-improv spirit,” writes Hermes, “[Zorn] suggested the two musicians collaborate. ‘Lou asked me to read something with his band,’ Anderson recalled. ‘I did, and it was loud and intense and lots of fun.’” The rest was history, and looking back on it, Zorn said of the Reed-Anderson pairing, “It’s the love affair of a lifetime.” Reed went on to do several more projects with Zorn, including a musical arrangement of the biblical Song of Songs – the Shir Hashirim – in which Reed and Anderson recited the lover’s text.

A Brooklyn kid made good

In his later years, Reed also collaborated with producer and all-around musical visionary Hal Willner, who was born and raised in Philadelphia, where his father and his uncle, Holocaust survivors, ran a deli called Hymie’s. Reed also worked with artist and filmmaker Julian Schnabel on the stage version of his album Berlin, which Reed had originally envisioned as a rock opera-musical. “They were both Brooklyn-Jewish kids made good, with personalities that veered between extremes of aggressive and tender,” writes Hermes. “You’ve got a nice Yiddishe kop there,” Schnabel said to Reed’s mother, Toby, who was seated up front with her daughter on opening night. “If he was my son, I’d be very proud of him.”

Around this time, Reed also reconnected with his cousin Shirley Novick. “In her late nineties, she remained quick-witted, and her rapid-fire banter with [Reed] was remarkable and reliably comic, in a Yiddish tradition,” writes Hermes. Novick, born Shulamit “Shirley” Rabinowitz in a shtetl near Bialystock in April 1909 into a family of Yiddish-speaking leftists in Poland, eventually immigrated to New York City by way of Canada. She left behind a husband and her parents, all of whom were presumably murdered in the Shoah. “Shirley’s third husband, Paul Novick, nearly twenty years her senior, was editor of the Yiddish-language Communist Party daily newspaper Morgen Freiheit, reputedly the largest-circulation Communist newspaper in the country, in any language, in the 1920s,” writes Hermes. “Shirley became a labor activist working in Jewish-run shops and, after she began getting blacklisted in them, Italian ones. She earned herself a nickname: Red Shirley.” Reed’s sister called Novick her brother’s “spiritual grandmother.” Reed made a half-hour film about her called Red Shirley, mostly comprising a conversation with his firebrand cousin.

Reed was not known to have ever practiced Jewish rituals, other than his near-annual participation in the Downtown Seders hosted by the Knitting Factory and later City Winery. He was a longtime adept of tai-chi, and if he followed a religious philosophy, it was likely more Buddhist than Jewish. Reed died Oct. 27, 2013, at the relatively young age of 71. In contravention of Jewish law, Reed’s body was cremated. His immediately family, however, sat shiva for him. Ten days after his death, Reed’s mother passed away.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO