How my story about Nazi-looted art inspired an opera by one of America’s greatest composers

‘Before It All Goes Dark’ started life as an article in the Chicago Tribune

Howard Reich’s two-part story was published in 2002 in the Chicago Tribune. Courtesy of Howard Reich

It isn’t often that a newspaper series becomes an opera — let alone a Holocaust-themed opus by one of America’s most revered composers.

But that’s about to happen to a collection of articles I published more than two decades ago in the Chicago Tribune, where I covered music from 1978 to 2021.

Later this month, Before It All Goes Dark – by composer Jake Heggie and librettist Gene Scheer — will have its world-premiere tour in Seattle, San Francisco and Chicago. Heggie is celebrated around the world for his opera Dead Man Walking (based on Sister Helen Prejean’s book and the film of the same name), and for Moby Dick and other works he created with the comparably gifted Scheer.

The new opera will bring to the stage a narrative I wrote more than 20 years ago and had just about forgotten – until the evening Heggie and I dined together in Chicago in December 2021.

That night Heggie told me that Seattle-based Music of Remembrance, which commissions works on the Holocaust and other social-justice issues, had asked him to create a new opera. Mina Miller, Music of Remembrance’s founder and artistic director, wanted to mark the organization’s 25th anniversary in a big way, and an opera seemed about right.

But Heggie didn’t yet have a story.

So — as critics love to do — I offered some unsolicited advice: I observed that although there had been several Holocaust-related operas, I didn’t know of any that dealt with the fraught subject of looted art.

And then suddenly I remembered a story that had haunted me at the time but had long since faded from memory.

In 2001, I was working on an article about rare stringed instruments seized by the Nazis that now were worth millions — but had ended up in the wrong hands.

When I called the Art Loss Register, which tracks stolen cultural treasures, to see if they had any leads on looted fiddles, they said they didn’t. But they quickly offered another tantalizing possibility: They said that the Jewish Museum in Prague had recently proven that 30 paintings in the National Gallery there had been owned by Emil Freund, a prominent Czech Jew murdered during the Holocaust.

The democratic government in the Czech Republic had mandated that the Jewish Museum find heirs and return the art. But neither the museum nor the Art Loss Register could figure out who the heir might be.

And so they asked: Might I be willing to try identifying the heir? Because Freund had two sisters, the Art Loss Register wondered if those siblings might have lived in Chicago, which has long had a large Czech population.

As the son of two Holocaust survivors, I decided to accept the challenge, and I soon found death notices for Freund’s sisters — Berta Sieben and Olga Hoppe. Lo and behold, they indeed had lived in Chicago since at least the 1920s. Then I worked on finding the death notices of their children and the generations after that, from which I built a family tree.

Which led me to a man named Gerald McDonald.

The Internet was not nearly as ubiquitous as it is today, so though voter registration records told me he lived in the Chicago suburb of Lyons, I didn’t have his phone number. When I knocked on his door, the heavy-metal music he was playing inside was so loud he couldn’t hear me. After a tense and seemingly interminable 20 minutes, the door opened, and I saw a large man wearing jeans and a T-shirt, his arms and neck swathed in tattoos.

“I’m Howard Reich from the Chicago Tribune,” I said. “And if you’re who I think you are, you’re heir to a priceless art collection looted in Prague during the Holocaust.”

I was a bit surprised when this giant of a man gently said, “Come in, please.”

I waited inside his living room as he disappeared elsewhere in the small house; then he reappeared holding a little tin box. Inside were birth, death and marriage certificates of many of the people on the family tree I had made, meaning that Gerald McDonald — or “Mac,” as I soon learned everyone called him — was indeed Emil Freund’s heir.

It turned out that Mac had his own tragic story. He served in the Navy in Vietnam, and had been diagnosed with Hepatitis C and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. He had been married and divorced three times, was awaiting a liver transplant, living on disability checks and did not know of his Jewish heritage.

I spent the next couple months confirming Mac’s account of his life and otherwise fleshing out the story, which appeared on the Tribune’s front page on Dec. 30, 2001.

Three weeks after I had told the world that I could prove Mac was heir to the collection, the Jewish Museum in Prague received a letter from the Czech Culture Ministry. It said the ministry was considering designating the most valuable works in Freund’s collection as national cultural treasures. As such, they would not receive an export license and therefore could not leave the country or be sold on the international market.

In addition, the ministry warned the museum that it must protect the works from “misappropriation.” This was rather rich, considering that the paintings had been looted by the Nazis during the Holocaust, nationalized by the communist government of Czechoslovakia after the war and now were in the process of being misappropriated anew.

The Czech Culture Ministry indeed soon declared the most valuable 14 of the 30 works as national cultural treasures, including Paul Signac’s “Riverboat on the Seine” and Andre Derain’s “Head of Young Woman.”

Not surprisingly Mac was incensed and wasn’t going to take this lying down. Though sick and poor, he decided to go to Prague to look at his paintings and see if he could get them. He borrowed $688 from friends for the plane ticket, packed one suitcase with clothes and one with medicine, bought a new pair of blue suede boots and flew to Prague — with me alongside.

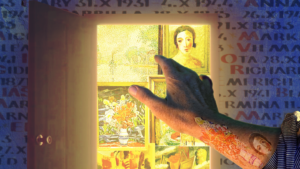

At the Jewish Museum, Mac was overwhelmed to see his great-great-uncle’s art works gathered in a single room; the brilliant Impressionist, post-Impressionist and avant-garde paintings said a great deal about Freund’s tastes and status in society. In effect, Mac was making contact with a long-lost relative he’d never known he had. Then Mac decided to go to Lodz, Poland, to see the ghetto to which Freund had been shipped and where he died in 1942, buried in an unmarked hole.

The Jewish Museum sued the Czech government over its obvious attempt to get around its own laws of returning art looted by the Nazis, but, not surprisingly, the government prevailed.

During our last night in Prague, Mac bought a $72 oil on canvas in the city’s Old Town, the only art he came home with.

After I told composer Heggie this story, he decided on the spot that this would be the subject of his Music of Remembrance opera, and so it is.

Ultimately, Heggie, librettist Scheer and I all came to the same conclusion: that although Mac never obtained his persecuted forebear’s art (Mac died in 2005 at age 55, after his long-awaited liver transplant), he got something perhaps more valuable: a family history he never knew and a connection to Judaism that he treasured.

I’ll never forget one of the last things he said to me, as we were boarding our plane home to Chicago.

“From here on, whenever anyone asks, I know what I’m going to say,” Mac told me. “I’ll say, ‘Yeah, I’m a Jew. I’m a Jew. ‘You got a problem with that?’”

Before It All Goes Dark plays May 19 in Seattle; May 22 in San Francisco; and May 25-26 in Chicago; for details and tickets visit musicofremembrance.org. Howard Reich can be reached at [email protected]

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO