On Paul Simon’s birthday, his 7 most Jewish songs

Although Simon is rarely thought of as a Jewish songwriter, a theological current runs through some of his work.

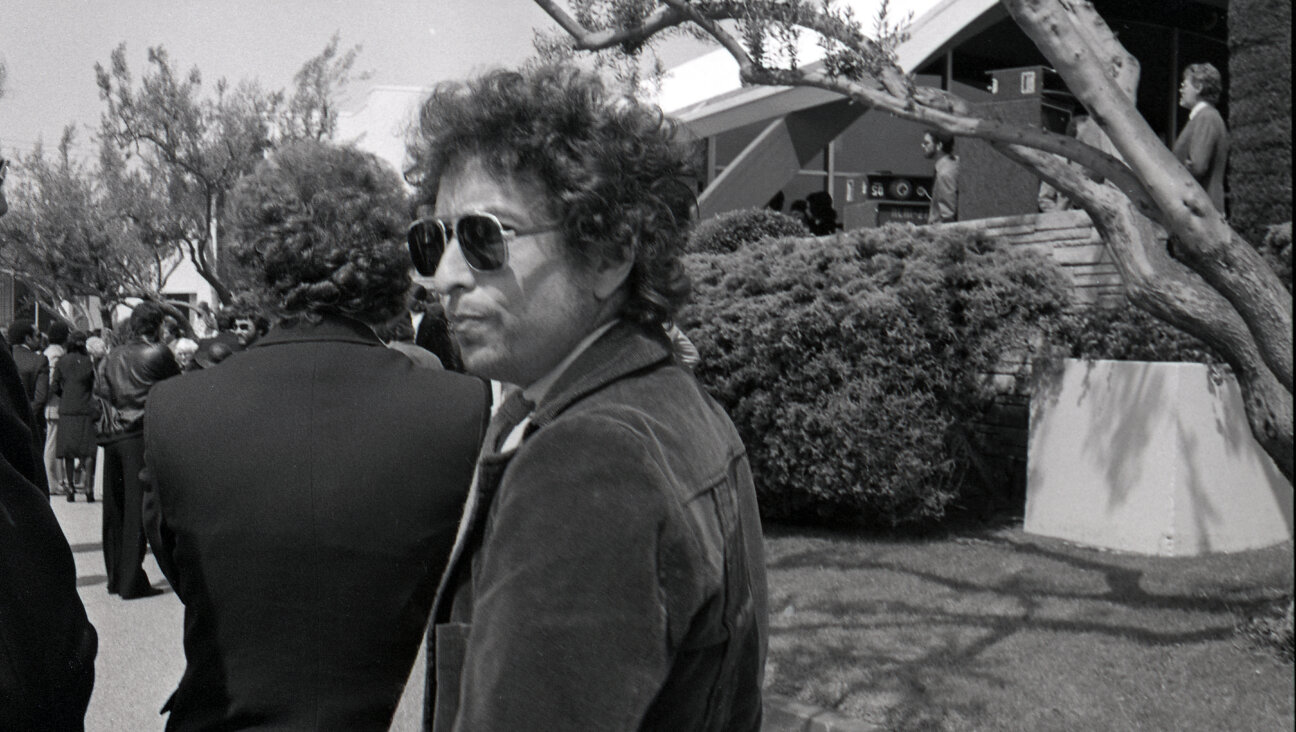

Paul Simon By Getty Images

Paul Simon’s legacy is truly astonishing, in some ways unequalled in the rock era. No other singer-songwriter functioning at his level — almost shoulder to shoulder with Bob Dylan, Leonard Cohen and Joni Mitchell — has enjoyed the combination of critical respect and commercial success that has been his steady companion since the mid-1960s, when, with his erstwhile singing partner, Art Garfunkel, he brought Dylan-style folk-rock poetry to the top of the pop charts. Simon’s string of solo albums in the 1970s spawned a plethora of hits, and with his landmark 1986 album, “Graceland,” he propelled “world music” into the pop stratosphere.

Unlike his tribesmen Dylan and Cohen, however, Simon is rarely thought of as a Jewish songwriter, and not often his songs the subject of theological analysis. (The work of Dylan and Cohen vis-à-vis their Jewishness has been the subject of full-length books.) A scan of just a few numbers suggests this might be an area worthy of deeper investigation.

1.

Silent Eyes

Written in the wake of the Yom Kippur war, “Silent Eyes” could well be Simon’s most Jewish song. It is manifestly about longing and weeping for Jerusalem in prayerlike phrases — “She is sorrow, sorrow / She burns like a flame / And she calls my name.” And it envisions a time when all will be called to account — “We shall all be called as witnesses / Each and every one / To stand before the eyes of God / And speak what was done.” It isn’t too much of a stretch to wonder if the Jerusalem of the song is a stand-in for the Jewish people. With its central image of “silent eyes,” its latent subject could actually be the Holocaust.

2.

Hearts and Bones

Simon’s wry sense of humor is probably his most overlooked quality. It’s no wonder he tells author Robert Hilburn, in the latter’s excellent new biography, “Paul Simon: The Life” (Simon & Schuster), that satirical songwriter Randy Newman is one of his favorites. In “Hearts and Bones,” Simon sings about his ill-fated relationship with Carrie Fisher, daughter of Debbie Reynolds and the American Jewish singer/actor Eddie Fisher. The first two lines of the song — “One and one-half wandering Jews / Free to wander wherever they choose” — are funny enough on their own. What follows, however, turns it into a complete joke: “Are traveling together in the Sangre de Christo / The Blood of Christ Mountains / Of New Mexico.” At the end of their rock journey, Simon tells us, “One and one-half wandering Jews / Returned to their natural coasts.”

3.

He Was My Brother

While Simon wrote this song about Northern activists traveling to the South before the slaying of Michael Schwerner, Andrew Goodman and James Chaney, he revisited the song afterward and wrote its final version in tribute to his fallen friend and Queens College classmate, Andrew Goodman, with whom he obviously identified. While at the college, Simon served as president of Alpha Epsilon Pi, the international Jewish fraternity.

4.

Fakin’ It

It’s clear from Hilburn’s biography that as much as Simon may have indeed been the notorious control freak of legend, he has also always felt a whopping sense of personal insecurity, especially in light of his monumental accomplishments. Recorded by Simon & Garfunkel in 1967, “Fakin’ It” betrays this sense of “impostor syndrome” when he sings, “And I know I’m fakin’ it / I’m not really makin’ it…. This feeling of fakin’ it — / I still haven’t shaken it.” He then seems to tie this feeling to his ancestral background when he muses, “Prior to this lifetime, I surely was a tailor… I own the tailor’s face and hands.” Simon was named after his paternal grandfather, Pinkas Seeman, a tailor from a shtetl in Ukraine who took the name Paul Simon when he immigrated to the United States.

5.

The Boxer

It’s often been suggested, including by Simon himself, that “The Boxer” was inspired by Simon’s reading of the Bible. But the most Jewish aspect of this song is hiding in plain sight: The “lie-la-lie” refrain is a nigun, an ecstatic wordless vocal chant of the kind favored by Hasidim. Just imagine Simon singing “yie-die-die” instead of “lie-la-lie,” and it should all make sense.

6.

The Afterlife

Simon’s sense of humor is operating on all four cylinders in this wry portrayal of heaven as just another bureaucracy: “You got to fill out a form first / And then you wait in the line… Buddha and Moses and all the noses from narrow to flat / Had to stand in the line / Just to glimpse the divine / What you think about that?” Theology meets the Depatment of Motor Vehicles.

7.

How Can You Live in the Northeast?

While this song seems to question any religious belief at all — “How can you be a Christian? / How can you be a Jew? / How can you be a Muslim, a Buddhist, a Hindu?” — it is filled with Jewish imagery. Simon refers to the Sabbath — “Everyone hears an inner voice / A day at the end of the week / To wonder and rejoice.” He discusses Jewish prohibitions and customs — “How can you tattoo your body? / Why do you cover your head?” — and in the final verse, he seems to park himself solidly in the tradition of his ancestors: “I’ve been given all I wanted / Only three generations off the boat / I have harvested and I have planted / I am wearing my father’s old coat.”

Spoken like the true grandson of a tailor.

Seth Rogovoy is a contributing editor at the Forward and is the author of “Bob Dylan: Prophet, Mystic, Poet” (Scribner, 2009).

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO