The Secret Jewish History of Roger Daltrey

Roger Daltrey Image by Getty Images

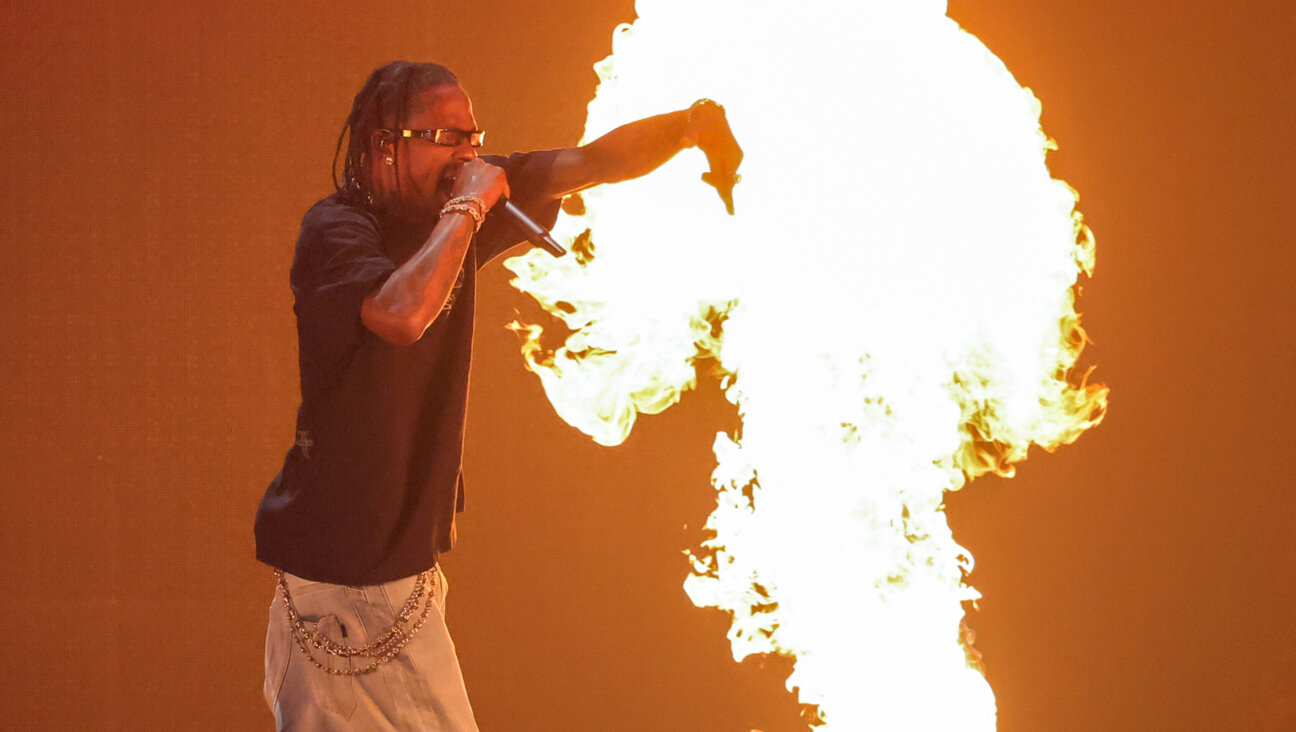

In his new memoir, “Thanks a Lot, Mr. Kibblewhite: My Story” (Henry Holt) – a horribly titled but entertaining and revealing read — Roger Daltrey gives his version of the story of the rock band, the Who, territory that his bandmate and on-again, off-again friend and collaborator, Pete Townshend, already reviewed in his own chronicle, “Who I Am.” Like Townshend, Daltrey pays tribute to the group’s early Jewish managers and to the Mod fashions the group adopted, created by tailors in Jewish East London He also recounts paths crossed with two of the most notorious Jewish gangsters of all time, and the surprise of learning that he had a Jewish daughter.

Born and raised in the rough, working-class neighborhoods of heavily-bombed Acton and Shepherd’s Bush, Daltrey, like so many other British would-be rockers of his generation, got bitten by the rock ‘n’ roll bug as a young teenager, when the sounds of Elvis Presley and Bill Haley first entered England’s dreaming. Having left school at an early age, Daltrey was hired by a small metalworking shop, primarily as a tea-boy (they take their tea seriously over in England) before graduating to hands-on work as a cutter and fitter. For Daltrey, most of the motivation for showing up for work each day was so he could pinch tools and materials from the site to aid him in building his own guitars, until he could afford to buy a real one.

Daltrey hooked up with some likeminded friends, and by 1959 they were gigging around as a Mod band called the Detours. Mods wore tailored suits and were fond of modern jazz, Italian and French cinema, and motor scooters. The Mod subculture was very much a product of London’s Jewish East End. The antithesis of Mods were rockers, who favored leather jackets, motorcycles, American rock ‘n’ roll, and pompadours – think early Beatles or what we in America used to call “greasers.” (The competition between Mods and rockers, which included violent encounters, would be the subject of the Who’s 1973 rock opera, “Quadrophenia.”) While never fully committed to the Mod lifestyle, being identified as Mods helped the Detours establish their identity at a time when their image might have mattered more than their level of skill.

Around that time, the Detours frequently gigged at a Jewish club in Ealing, presumably explaining why Daltrey made Pete Townshend play “Hava Nagila” when he auditioned for the guitar slot in the band. By spring 1964, the Detours attracted their first manager. “Helmut Gordon was a Jewish German doorknob manufacturer who wanted to be the next Brian Epstein,” writes Daltrey, referring to the Jewish visionary who steered a scruffy foursome of Liverpudlians to fame and fortune as a combo called the Beatles. Gordon had money “to waste on a rock band,” writes Daltrey, and he bought them a van, professional amplifiers, and paid for studio time for their initial recordings.

The next manager was Pete Meaden, whose father, Stanley Meaden, was “half Jewish,” according to Daltrey. More importantly, Meaden was business partners with a guy named Andrew Loog Oldham, a fellow Jew who happened to manage an up-and-coming electric blues group by the name of the Rolling Stones. The Detours suddenly found themselves in good company – at least management-wise.

The Who – as the Detours became known, after a brief, unsuccessful stint as the High Numbers – never quite caught on at the level of their rivals. Perhaps it had something to do with their personalities. Bassist John Entwistle aka “the Ox” had the demeanor of … well, let’s just say that he had something in common with the alcoholic child abuser Uncle Ernie in the Who’s rock opera “Tommy.” The violent antics of Keith Moon, who seemingly never met a hotel room he didn’t trash, threatened to overshadow his wild genius at the drum kit. Townshend, the group’s guitarist and chief songwriter, is portrayed by Daltrey as a tortured artist and misanthrope who was perhaps happiest when creating at home on his own with the aid of his intoxicant of the moment fueling his vision or stemming his pain, or both. Daltrey portrays himself as a straight arrow who rarely indulged in illicit substances and just wanted to stand onstage and sing the great songs that Townshend wrote for him, but he offers little sense of any camaraderie among the foursome. The Beatles they were not.

Daltrey does pay tribute to Townshend’s creativity, however, singling out the latter’s 1967 song, “Rael” (a diminution of “Israel”), as a bit of political prophecy. Daltrey quotes Townshend’s lyrics: “The Red Chins in their millions / Will overspill their borders / And chaos then will reign in our Rael.” Townshend, says Daltrey, “wrote that in the autumn of 1967, six years before the Yom Kippur War, and half a century later look where we are with the world. History repeats itself. It repeats itself far too often and ‘Rael’ was prophetic, Pete was prophetic… He was trying to do more than just write another pop song.” Daltrey also offers that sending the title character of the rock opera “Tommy” to a “holiday camp” was in fact a bad, fumbled joke about Nazi concentration camps, about which he felt so awful that he apologized to his Jewish friends at the time.

Daltrey had two brushes with a couple of twin brothers by the name of Kray, infamous gangsters who claimed Romany, Irish, and Jewish ancestry. He once unknowingly borrowed cash from them (presumably from one of their “representatives”), and fortunately for him, he paid up on time. Later in life, when Daltrey became involved in movies as an actor and producer, he almost bought the film rights to their story. When in the end he realized that he would be negotiating with people who directly represented the Krays’ interests, he withdrew from the project, figuring that was a road better left untraveled.

After decades of rooting for the Queens Park Rangers football club, as would be expected of a Shepherd’s Bush native, Daltrey let go of his allegiance in the early 1970s, when fan violence began to overshadow what was happening on the field. Later on, when his son turned 10 and declared himself a fan of Arsenal — the team favored overwhelmingly by North London’s Jewish community — Daltrey jumped on board, and with the help of an employee in his manager’s office named Robert Rosenberg, he and his son became regulars at the team’s home games.

On his 50th birthday, March 1, 1994, Daltrey received a letter and photograph from a 27-year-old “Jewish girl” named Kim. One look at the photo and Daltrey had no question that she was his daughter, one of several, far-flung offspring, the products of rock ‘n’ roll dalliances. “I don’t even remember meeting her,” Daltrey writes of Kim’s mother. “I remember the mother of my Scottish daughter, my Swedish son, and my daughter who lived in Yorkshire.” But Daltrey established a relationship with her, as he has with all his various children. Such a mentsh he is.

Seth Rogovoy is a contributing editor at the Forward. He frequently mines popular culture for its hidden and surprising Jewish stories.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO