Did George Gershwin Plagiarize From Broadway’s ‘Shuffle Along?’

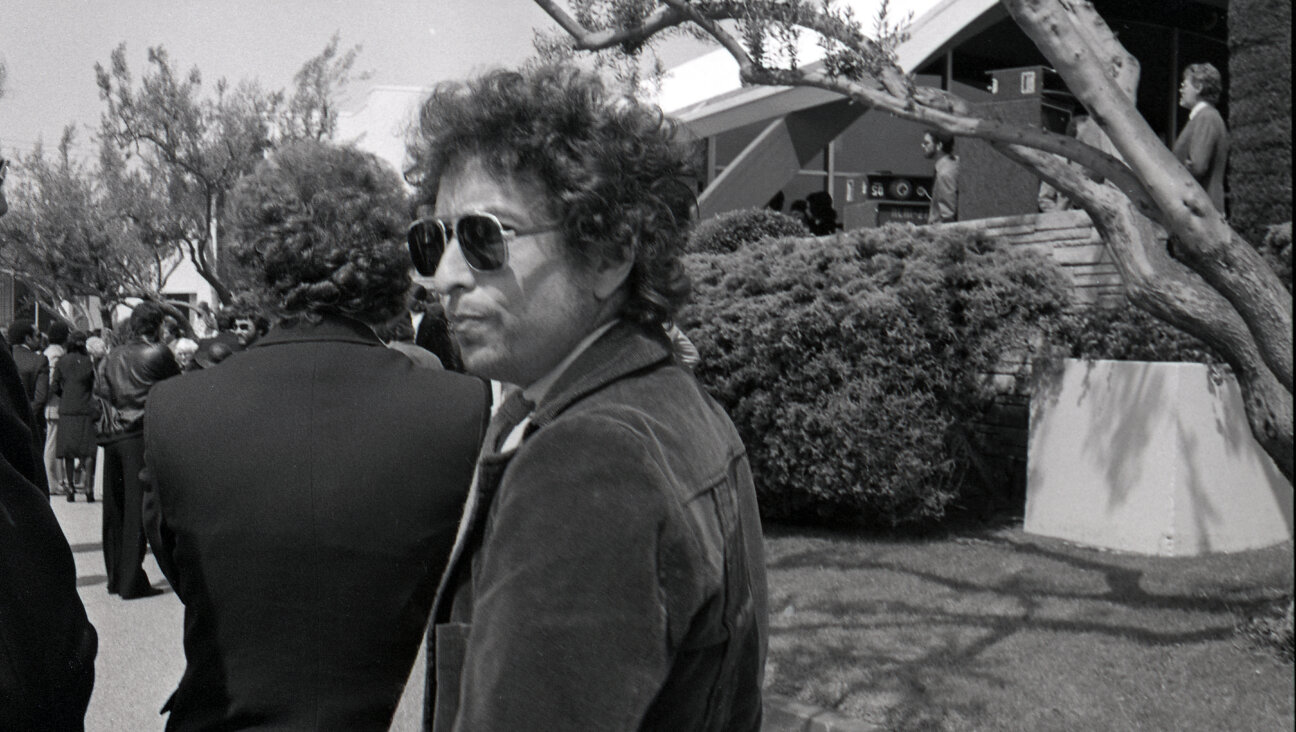

Image by Julieta Cervantes

“Shuffle Along, Or The Making of the Musical Sensation of 1921,” the Broadway show starring Audra McDonald, opened on April 28. Its book by George C. Wolfe purports to explain how the African-American songwriter Eubie Blake encountered difficulties along the way to producing a show, “Shuffle Along,” nearly a century ago. One of the key plot points of the new “Shuffle Along” is that the American Jewish composer George Gershwin supposedly came to see the original show three times to hear the 25-year-old African-American oboist, arranger, and aspiring composer William Grant Still warm up in the orchestra pit before the performance. Captivated by four notes improvised by Still, the wealthy white composer Gershwin lifted them to use in his hit song “I Got Rhythm.” The reality is rather different.

It is unsure how many times Gershwin (1898-1937) saw “Shuffle Along,” although he is presumed to have visited it at least once. At 22, Gershwin was no figure of wealth or privilege; he had barely begun his Broadway composing career and would write “I Got Rhythm” in 1930, several years after seeing “Shuffle Along.” Still would begin composing in earnest only in 1924, and used those same four notes in his Symphony No. 1 “Afro-American” (1930) where they appear only once, in wistfully evanescent form. The four notes were used by the composers in entirely different ways, Gershwin for a swaggering upbeat tune belted by Ethel Merman, and Still a bluesier, nostalgic message.

The Gershwin musical “Girl Crazy,” including “I Got Rhythm,” opened on Broadway in October 1930, two weeks before Still began to compose his symphony. Even presuming that Gershwin had heard and been captivated years before by four notes from an unpublished work played on an oboe during a warmup session, this hardly amounts to plagiarism. Wolfe’s assertion sets up Gershwin as a symbol for the many times African-American composers were genuinely ripped off by the music industry. The choice of Gershwin for this straw man role is questionable in the extreme. Gershwin was vocal about the inspiration he drew from African-American musicians, and insisted that his “Porgy and Bess” always be performed by black performers, not just in America but around the world, where this casting stricture prevented some productions from occurring. Generations of African-American performers have launched careers in “Porgy,” not least the great soprano Leontyne Price.

Still himself never directly accused Gershwin of any such theft. Where did the Gershwin-as-thief bubbe-meise begin? Catherine Parsons Smith’s “William Grant Still: A Study in Contradictions” recounts anecdotes, such as a 1973 interview with an almost-nonagenarian Eubie Blake, who claimed that Still would often play the four notes, until one day Gershwin used them in “I Got Rhythm.” Blake added: “Gershwin heard the tune and took it. Now Gershwin probably didn’t mean to take it or steal it because he didn’t have to. The man was a genius! But that tune was Still’s tune. It could happen to anyone.”

Smith notes that “Blake’s version is demonstrably inaccurate on at least one point.” Howard Pollack’s “George Gershwin: His Life and Work” recounts that Blake also believed that Gershwin had adapted “Rialto Ripples,” a piano work, from a theme by Luckey Roberts. The latter, an African-American pianist and real estate tycoon, later claimed in turn that he had written Gershwin’s song “The Man I Love” and that Fats Waller had composed the aria “Summertime” from “Porgy and Bess.” Some of these implausible rumors were believed by biographers, such as Joan Peyser in “The Memory of All That: The Life of George Gershwin.”

Yet in October 1935, Still wrote to a friend that Gershwin’s “Porgy” “met with success in New York, and I am glad,” implying a lack of resentment or any sense of victimization. Nor had Still any reason, at least then, to resent Jewish musicians, since many championed his early works, including the Austrian Jewish conductor Richard Lert (1885-1980). Still’s wife Verna Arvey (1910 –1987), a pianist and journalist, was herself of Russian Jewish stock.

As the 1930s wore on, Still’s work in the folksy, dance-driven idiom of American ballets of the era was notable for its gracious elegance and refinement of discourse. Unfortunately for Still, this graciousness became unfashionable in strident times. In a 1935 issue of “Modern Music,” the American Jewish composer Marc Blitzstein, a leftist, slated Still’s Afro-American Symphony for its “servility” and “willingness to debauch a true folk-lore for high-class concert-hall consumption.” Aaron Copland, another American Jewish leftist composer, also expressed reserves, writing of Still: “He has a certain natural musicality and charm, but there is a marked leaning toward the sweetly saccharine…often based on the slushier side of jazz.”

Still’s works became increasingly neglected in the 1940s. Starting in 1949, in speeches and prose writings, Still repeatedly accused American Jewish musicians who did not admire his music of being Communists. In “Fifty Years of Progress in Music,” a 1952 essay, Still claimed:

“It is a fact that there is in New York a powerful clique of white composers who exclude all others, white as well as colored… . It is interesting to know that Aaron Copland and Leonard Bernstein, the leaders of the clique, were also publicized in Life magazine’s April 4, 1949, issue, in an expose of ‘Dupes and Fellow Travelers.’ The connection is all too obvious! Having refused to follow Leftist doctrines, certain colored and white composers have been opposed by this clique for many years. Among other things, the door to adequate recordings of our music—always a sore spot—has been closed to us. Thus the New York clique had made a totally unnecessary obstacle for many of us—an obstacle that has wider implications than the merely racial or personal.”

At the height of the McCarthy era, under no subpoena, Still voluntarily branded rival composers as Communists, apparently out of professional pique. In “Communism in Music,” a 1953 speech delivered in San Jose, California, Still disingenuously claimed to be merely mentioning a “series of coincidences” rather than branding people as Communists. He then named names in the style of a voluble cooperative witness before the House Un-American Activities Committee, although no one had solicited his denunciations. Among those he blamed for furthering Moscow’s “subtle but effective hand” were Copland as a “member of twenty-eight communist-front groups,” Bernstein, Blitzstein, conductor Serge Koussevitzky, and composer Kurt Weill. That Weill had died in 1950 mattered not to Still, who also incriminated others “whose names appear on such lists [of un-Americans] regularly,” including the harmonica virtuoso Larry Adler, composer Morton Gould, screenwriter Garson Kanin, and the lyricists Oscar Hammerstein and Ira Gershwin. The last-mentioned, of course, was the brother of the long-dead George Gershwin and author of the lyrics of “I Got Rhythm.” In this document and others like it, Still may have felt that he achieved a sense of revenge, but surely he disqualified himself from heroic victimhood on today’s Broadway stage.

Benjamin Ivry is a frequent contributor to the Forward.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO