The Secret Jewish History of Patti Smith

Religious context: Patti Smith’s “M Train” touches on her relationship with religion. Image by Getty Images

The first words ever uttered by Patti Smith on a recording were “Jesus died for somebody’s sins but not mine,” the opening line of “Gloria” on her debut album, “Horses,” released 40 years ago this December.

That line pretty much set the tone for what was to come over the next four decades. Much of Smith’s recorded work has been laden with biblical imagery and poetic renderings of the singer’s struggles with religion, belief and God, such that the sum total of her oeuvre can be viewed as a kind of personal theology.

“I have a very strong biblical background,” Smith once told Rolling Stone. “I studied the Bible quite a bit when I was young and continue to study it, independent of any religion, but I still study it.”

No kidding.

While many took Smith’s declaration of independence from original sin to be a stab at religious doctrine, it was in fact more like a mission statement for her career that, while challenging the dictates of her strict religious upbringing in a family of Jehovah’s Witnesses, very much embraced the poetic tradition of the Bible and the Prophets along with their themes of redemption and resurrection. Not for nothing was Smith’s third album named “Easter.” It’s not too far of a stretch to say that her song-poems cannot be fully understood or appreciated without consideration of their religious context.

Smith is in the news again, not for a new recording but for a new memoir, “M Train,” the follow-up to her National Book Award-winning “Just Kids,” a recollection of her formative years as an artist and her close bond with artist-photographer Robert Mapplethorpe. “Just Kids” was all about births and beginnings — recounting her early days in the East Village and at the Chelsea Hotel, where she met, befriended and collaborated with a cast of characters that included playwright-actor Sam Shepard; Beat poets Allen Ginsberg and Gregory Corso, and their ringleader, writer William S. Burroughs; folklorist-filmmaker Harry Smith; nightclub owner Hillel “Hilly” Kristal; rock guitarists Allen Lanier (of Blue Oyster Cult) and Tom Verlaine (of Television]), and the man who would become her go-to guitarist and lifelong musical collaborator, writer-guitarist Lenny Kaye.

“M Train,” by contrast, is quiet, solemn and introspective. It reads like a beautifully wrought journal — part travelogue (even if the trip is merely across the street, to her favorite Greenwich Village cafe, but also includes jaunts to Japan, Tangier, London, British Guiana and Mexico) and part exercise in grief and mourning, cataloging her life and struggles in the wake of the sudden death of her husband and the father of her children, Fred “Sonic” Smith, followed immediately by the loss of her beloved brother, Todd Smith. It’s Smith’s version of Joan Didion’s National Book Award-winning “The Year of Magical Thinking,” about the loss of her husband, John Gregory Dunne. There’s almost no mention of music in “M Train,” and the protagonist is portrayed primarily as a writer and occasional visual artist, a lone wolf who keeps to herself, bringing Smith back full circle to how she saw herself as a budding poet and artist in the early sections of “Just Kids.”

Rock icon Smith, the so-called godmother of punk, was something of an accident, the result of having invited Kaye to improvise some sounds behind her as she gave one of her first poetry readings at St. Mark’s Church in 1971. With the addition of pianist Richard Sohl — like Kaye, a Jewish native of Queens — to the music mix, the poetry readings became equal parts performance and poetry. And like Lou Reed before her, with the Velvet Underground, Smith became a rock ’n’ roll performance poet — in Smith’s case, as part of a fertile scene that aligned her with the burgeoning genre of punk rock. This genre’s home base was Kristal’s nightclub, CBGB, which in an interview with the Forward, Kaye once likened to a ghetto: “CBGB’s was a kind of strange ghetto with its own vocabulary and customs.” Speaking about the inordinate number of Jews and their influence on the ethos of the punk scene, Kaye pointed to its “love of the minor key, a sense of community and clan.”

The Patti Smith Group became standard-bearers for the scene, and record biz honcho Clive Davis, a native of Brooklyn’s Crown Heights, signed them to Arista Records, pairing them with ex-Velvet Underground member John Cale as producer. “Horses” was released in December 1975, just a few months after Smith’s fellow New Jersey native, Bruce Springsteen, garnered the covers of Time and Newsweek in the wake of his triumphant mainstream hit, “Born To Run.”

Image by Getty Images

Smith once confessed to a writer for the Los Angeles Times: “I’ve read the Bible quite a bit, there’s a lot of poetry in it — the Song of Solomon and the Psalms, a lot of poetry in Isaiah. So I tried to find language that wouldn’t be difficult to sing but wouldn’t feel out of place in this biblical setting.” This goes far to explain perhaps the most overlooked aspect of her song-poems, from the immortal opening line of “Gloria,” mentioned above, to “People Have the Power,” perhaps her greatest political protest song and transmogrification of the words of the Prophets into a stadium sing-along:

and the shepherds and the soldiers

lay beneath the stars

exchanging visions

and laying arms

to waste in the dust (ref. Hosea 2:21)

and the leopard

and the lamb

lay together truly bound (ref. Isaiah 11:6)

Where there were deserts

I saw fountains (ref. Exodus 15:27)

Similarly, her song “Waiting Underground” refers to Hebrew burial shrouds and alludes to Isaiah 26:19, which foretells the resurrection of the dead upon the appearance of the Messiah:

and then we will arise

in our snow-white shrouds

when we’ll be as one

but until that day we will just await

in our snow-white shrouds

waiting underground

And her song “Jubilee” borrows its imagery of land and slaves being freed from the concept of the Jubilee year as expounded in Leviticus 25:8-13:

Freedom ring Freedom ring

Jubilee Oh my land

Oh glad day Oh my land

Hear our cry Freedom ring

In a 1996 interview with NPR’s Terry Gross, Smith revealed that after breaking away from the Jehovah’s Witnesses as a 13-year-old, she was drawn to Judaism, partly, like many an American girl of that age, through her reading of “The Diary of Anne Frank.” Smith told Gross, “I had great sympathy. I mean when I grew up, in the late ’50s and early ’60s … a lot of information came out about the Holocaust and there were trials, and things, and I felt devastated about that as a young girl, and I got very interested in the Jewish faith.” Smith even contemplated becoming Jewish, until she ran into the requirements placed on a would-be convert: “I didn’t realize that you just can’t be, you don’t turn Jewish.”

Smith’s fascination with Jewishness, however, remains. A motif running throughout “M Train” is that of loss, whether it be the loss of possessions — Smith is perpetually leaving behind articles of sentimental and economic value — or the loss of loved ones. She contrasts the loss of a beloved black overcoat to the tragic loss of a creative work, referencing Bruno Schulz, the Polish Jewish author whose crowning achievement, “The Messiah,” perished in an unpublished manuscript, along with Schulz, in the Holocaust.

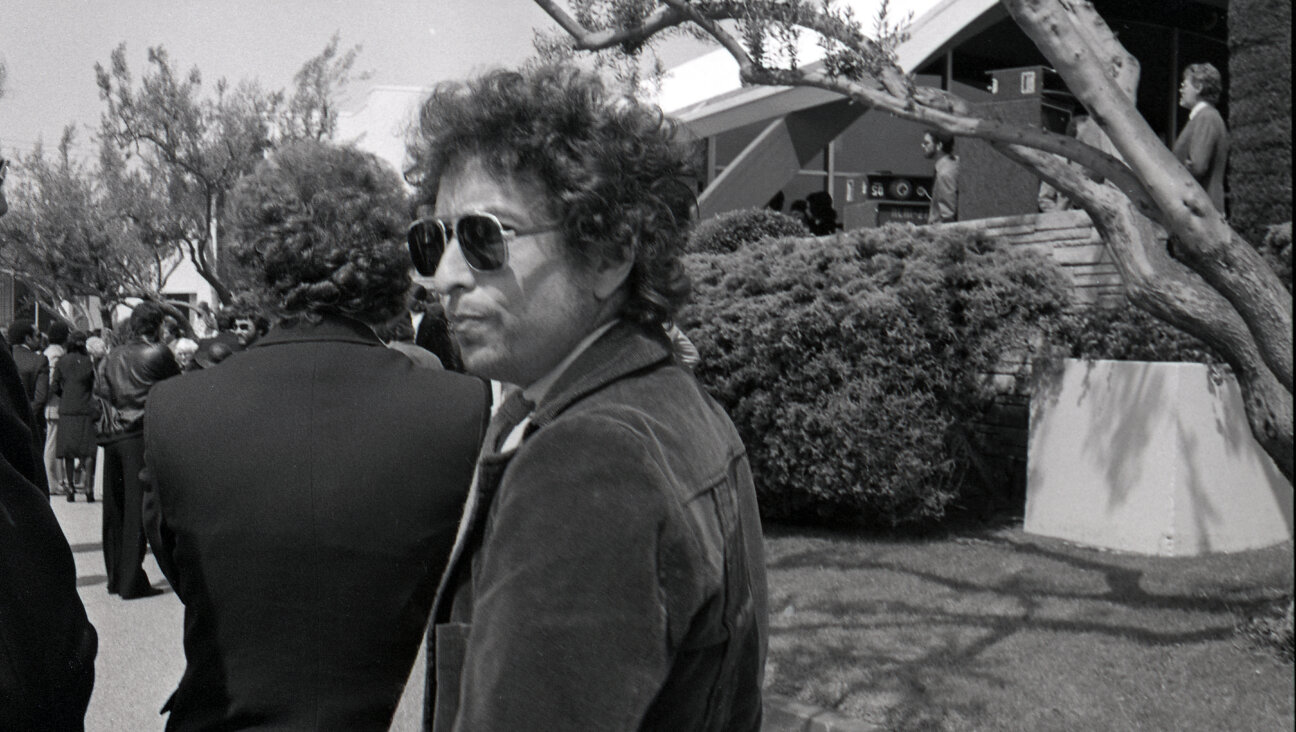

It’s not surprising that so many of her friends, heroes, collaborators and role models are Jewish – including Bob Dylan, who has variously filled all those roles for Smith, being an early supporter who gave his imprimatur to her work by showing up at early club gigs in the Village; by inviting her to join the Rolling Thunder Revue (Smith was unable to make the gig, as it conflicted with her own tour on the heels of the release of “Horses”); by coming to her rescue in 1995, the year after Fred Smith’s death, when Smith was languishing creatively, emotionally and financially, and by luring her out of seclusion to tour with him as his opening act, leading to a kind of creative resurrection for Smith that continues to this day.

But in “M Train,” Smith reveals perhaps for the first time that her earliest and perhaps most enduring role model was the Mexican Jewish artist Frida Kahlo, Smith has made two pilgrimages to La Casa Azul (The Blue House) in Coyoacán, Mexico City, where Kahlo grew up. Smith’s obsession with Kahlo, sparked by a gift from her mother when she was 16 of a book about Diego Rivera, would prove fortuitous, as Smith would go on to live a life that in many ways parallels Kahlo’s — as a proto-feminist and female artist breaking new ground in her field as a woman, while often willingly subsuming herself to her artist-lovers. Smith infused her work with Jewish and Christian imagery and became a seminal influence on several generations of artists to follow, a friend and mentor to the likes of REM’s Michael Stipe, and a role model to countless female rockers and performance poets ranging from Courtney Love to my dear friend, the late Maggie Estep.

On the song “La Mer (de),” part of her opus “Land” on “Horses,” Smith sang, “At the Tower of Babel, they knew what they were after.” In hindsight, Smith was singing about herself. She once described her work as “three chords merged with the power of the word.” That is as pithy a description of the biblical prophets as any.

Seth Rogovoy frequently mines popular culture for unlikely Jewish affinities for the Forward. He is the author of “Bob Dylan: Prophet, Mystic, Poet” (Scribner 2009).

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO