Who Will Be the Next Itzhak Perlman?

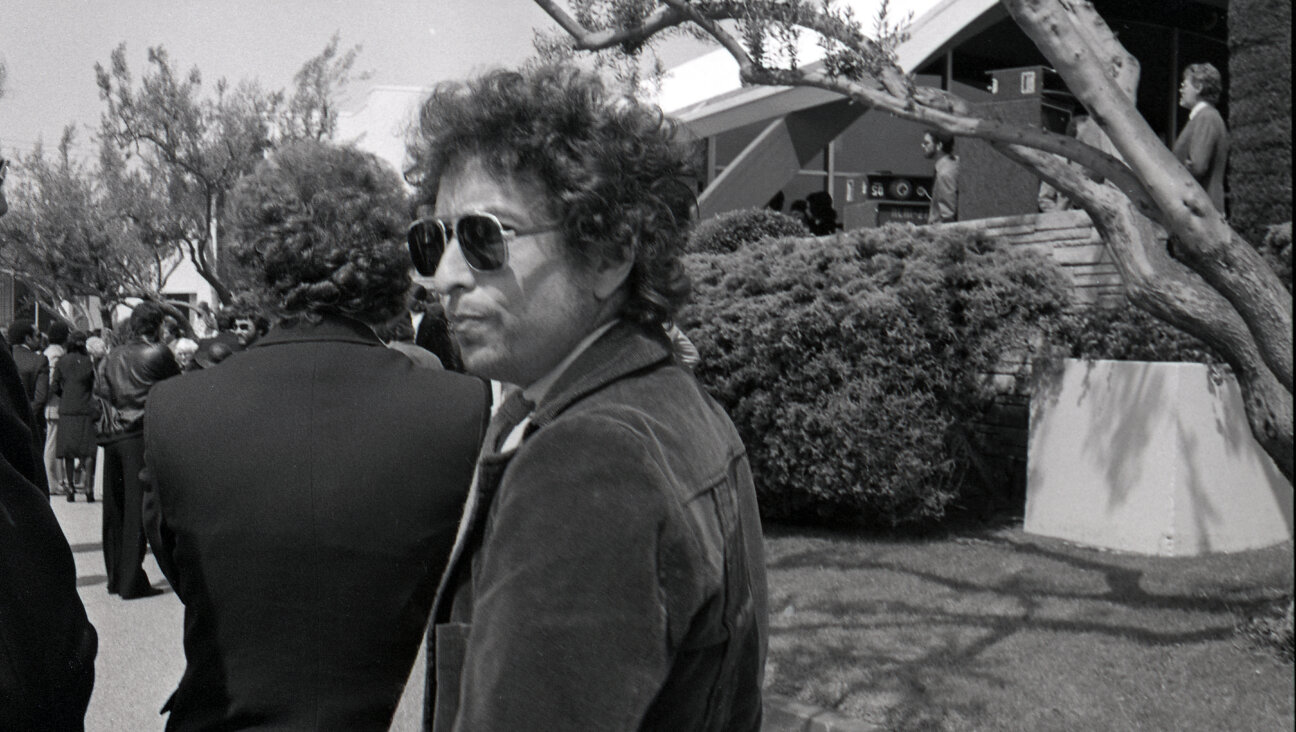

Image by Getty Images

On August 31, the superstar Israeli-American violinist Itzhak Perlman turns 70, and amid the mazel tovs, music lovers might wonder who will take over his prominent role in musical life when he is ready to retire. Fiddling is a demanding profession, rarely pursued at its highest levels by septuagenarians. Even the Olympian Jascha Heifetz scaled down his performing schedule around that age. Aplomb has been a keyword of Perlman’s achievement, since his appearances over a half-century ago on “The Ed Sullivan Show,” and his 1972 recording of the Paganini “Caprices.” His approach seemed to shrug off difficulties — and even some apparent impossibilities — with sangfroid. In his prime, the sweet tone of his renditions seemed to make light of the ferocious technical demands of the works he tackled. And sometimes he surprised in offering noble and forthright versions of unexpected repertory, such as an unusually rigorous and angular Bach “Double Concerto for Two Violins in D minor” with Isaac Stern and the New York Philharmonic led by Zubin Mehta.

Of late, Perlman’s technique is naturally not what it once was, but audiences still crowd his concerts to revel in the warm music-making and humorous personality that have made him a household name. The matter-of-fact way he has addressed the physical challenges that resulted from a childhood bout of polio, and his willingness to speak about issues for people with disabilities have also endeared him to audiences. Such openness is rare in the classical music world, where performers tend to prefer discretion about any physical difficulties which might be seen as potentially hampering their work; by contrast, as recently as last year, Perlman made public an unfortunate episode at the Toronto airport, where an Air Canada disability assistant proved less than accommodating.

Younger violinists will have quite an act to follow. Perlman’s ready assumption of the heroic mantle of the violin soloist, from Paganini to the Russian greats, is not easy to imitate. Yet there will surely be violinists as rewarding to listen to in the major repertoire, even if they do not dabble in film music or star on TV chat shows as Perlman has done. [The Ukrainian-born Israeli classical violinist Vadim Gluzman (born in 1973) is one example. A supremely able player, he has a somehow modest stance even when playing death-defying virtuoso pieces. Playing the concerto by screen composer Erich Wolfgang Korngold, which in other hands can drip with schmaltz, Gluzman expresses drama and a variety of emotions, validating the quasi-kitschy score. Gluzman’s Tchaikovsky Concerto is in the grand tradition, with plenty of glamor but also an interiorized, down-to-earth human quality. His impassioned, intensely imagined reading of the contemporary composer Sofia Gubaidulina’s “Offertorium” is equally stirring. He has also premiered music of quality by the Georgian composer Giya Kancheli, and the Latvian Pēteris Vasks. By contrast, Perlman has spent relatively little time with the music of today, explaining to an interviewer from Rollins College in 2013: “The problem with contemporary music is you need more than one listen to fully appreciate it and you usually don’t get that. People are always saying to me, ‘So how did you like it?’ And, you know, it’s a challenge. Instead of saying, ‘Oh I like it,’ I say, ‘I think it’s promising,’ because I want to hear it again.”

Contemporary and older music are specialties of Bracha Malkin (born in 1981), who studied with her father Isaac Malkin, a noted pedagogue born in Tajikistan. Although currently focusing more on raising a family than on promoting her career, the younger Malkin released a debut CD not long ago with an enchanting rendition of the Richard Strauss “Sonata for Violin and Piano in E-flat Major,” marked by narrative poise. She makes music tell a story in a way that is reminiscent of the highly personalized performers of yore, such as the Austrian Jewish titan Fritz Kreisler (1875-1962). Indeed, in 2008 the discerning critic Harris Goldsmith wrote:

“What makes Malkin so interesting is the unpredictable versatility of her interpretive style[s]. On the one hand, she can master the objective virtuoso writing of Berio’s ‘Sequenza VIII’; on the other, two performances of Kreisler’s ‘Caprice Viennoise’ were played with so much fleetness, flexibility, and charm, I almost thought that Kreisler himself had returned to our midst!”

Hopefully, Malkin will return to an active performing and recording career when she wishes to. During the heyday of Isaac Stern’s so-called “Kosher Nostra” of approved Jewish string players, of whom Perlman was indubitably one, non-Jewish fiddlers seemed to be the exception rather than the rule. Nowadays, the social context which made generations of Jewish parents compel their children to practice the violin has evaporated. No longer is it necessary to be admitted to a famous music conservatory class for a Jew to be allowed to dwell in a capital city. This was the case over a century ago in Russia for pupils of the Hungarian Jewish maestro Leopold Auer, who taught in Saint Petersburg. Today, if Jewish children are musically oriented they may choose any instrument, with the violin no longer as inevitable as it once was. Despite the enduring nostalgia of “Fiddler on the Roof,” the fact remains that a majority of today’s greatest solo violinists are not Jewish.

Still, most of these have assimilated lessons from great Jewish teachers and colleagues. They include the brilliant Taiwanese American violinist Cho-Liang Lin, (born 1960); Vadim Repin (born 1971) and Lisa Batiashvili (born 1979), both compatriots of Gluzman; the Latvian Baiba Skride (born 1981); Americans Rachel Barton Pine (born 1974), Jennifer Koh (born 1976), Sarah Chang (born 1980), and Joel Link (born 1988); Germany’s Julia Fischer (born 1983) and Christian Tetzlaff (born 1966); the Canadian Karen Gomyo (born 1982); and Janine Jansen (born 1978) from the Netherlands. All of the aforementioned “Trayf Nostra” are supreme artists well worth hearing, sharing in common only their lack of Jewishness. Does it matter that an instrument so long considered to be innately linked to Jewish traditions is largely dominated by non-Jews?

Perhaps it is a form of historical advance that the innately hysteric quality of the fiddle — deliberately tapping on listeners’ nerves with piercing high notes and lachrymose plaints — is no longer automatically associated with Jewish destiny. Such splendid artists as Gluzman and Malkin, among others — popular favorites also include Joshua Bell (born 1967) and Gil Shaham (born 1971) — still represent the mishpocheh. Meanwhile, the Juilliard professor and violin authority Monica Huggett suggested not long ago that the instrument itself may well have been invented by Spanish Jews, since it did not originate in Italy. This possible provenance is further indication that the legacy of Itzhak Perlman can never really lose its innate Judaism, whoever may carry on the tradition.

Benjamin Ivry is a frequent contributor to the Forward.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO