When Alvin Ailey Choreographs the Holocaust

American-Made: Like the ballet ‘Odetta’ (left), ‘No Longer Silent’ reflects on history. Image by Steve Wilson

With the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater presenting a Holocaust inspired piece, “No Longer Silent,” at the David H. Koch Theater at Lincoln Center, the iconic African American company has branched into new territory. In fact, it’s unprecedented, explained its artistic director Robert Battle, who choreographed the piece. Its musical score was composed by Erwin Schulhoff, a Czech-born Jew, and one of many musical artists who were killed or otherwise silenced by the Nazis.

“No Longer Silent” was conceived by Battle in 2007 as part of a Juilliard project — and the brainchild of conductor James Conlon — to commemorate three such composers, who include Franz Schreker and Alexander Zemlinsky.

“I was immediately drawn to Schuloff’s music for its urgency, rhythms, grandness, and ritualistic sounds,” said Battle as he sat in his corner office in the company’s West 55th Street complex. “It has tension and friction and reminded me of Stravinsky whom I love. It also reminded me of Martha Graham‘s early modern dance motifs. And then I got cold feet. Everything I loved about the music also terrified me.”

What finally anchored it for Battle was discovering just how much he and Schulhoff had in common. They both studied the piano, shared an interest in the avant-garde and jazz, and explored non-traditional artistic expressions in their own work. But there was also the human connection.

“His music was stifled, not allowed to be played because of who he was ethnically,” said Battle. “I thought, ‘Wow.’ Of course that had resonance for me as an African-American.”

Battle was further troubled and fascinated by Schulhoff because he was a man doomed by a lousy twist of fate. Schulhoff was finally accepted into Russia, but just before his papers arrived in 1941, he was captured and deported to the Wülzburg concentration camp in Bavaria, where he died of tuberculosis one year later.

“The tragedy is that he almost made it out and then boom, the door slammed,” Battle said. “It’s a whole other thing if there was never any light at the end of the tunnel. But here he was so close.” Turning on a cassette recorder, Battle held up his hand in a “listen to this” gesture.

A moment later the music — a pounding, percussive sound — poured out, suggesting marching or militaristic maneuvers of some kind. Although “Ogelala” was the name of an Indian chief in the original ballet and Schulhoff was influenced by Native American music, Battle said the music made him think about war, the Nazi regime and, by extension, the Holocaust.

But instead of choreographing a piece literally about the Holocaust, an undertaking which Battle dubbed “presumptuous,” he incorporated its powerful imagery — the scene and costumes metaphorically evoking a concentration camp — to forge an impressionistic narrative as if seen through the eyes of Schulhoff, who is a character in the piece, serving as witness and ghost.

Like every Holocaust victim or survivor, each character has his own story and reveals it through solos, duets and group pieces. The black costumes are deliberately baggy and ill-fitting, and each bears a clearly defined white strip encircling the leg. “It’s a marking,” said Battle. “They’ve all been marked.”

Battle removed photos from a folder, spreading them across his desk. These grainy black and white shots featured naked and emaciated corpses lying alongside each other in mass concentration camp graves. Other shocking photos showed half starved inmates listlessly sitting on a bench.

“There is a long bench at the back of the stage that stretches into the wings, like this one,” Battle pointed at one image. “Look at the people sitting there. It’s death before death. The bench becomes a metaphor. It’s so masculine, staid and Nazi.”

The power of the shots was not lost on the dancers. “Some gasped,” he recalled. “Others just stared silently.”

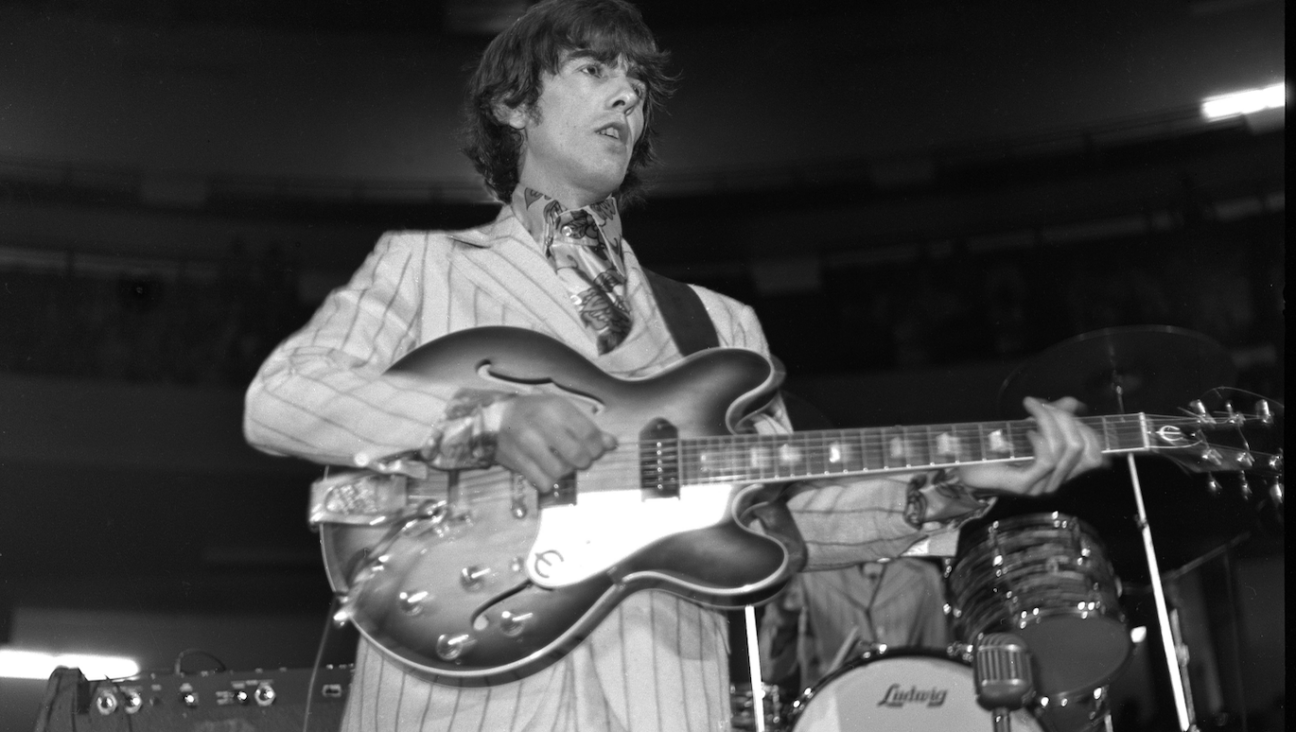

Company: Robert Battle (right, in suit) with the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. Image by Paul Kolnik

Before rehearsals began, Battle talked to the dancers about Schulhoff’s biography, the history of the era and the Holocaust, and parallels with the African-American experience.

“Look at this picture,” he said, showing me a photo of Jewish inmates with arms in the air, an image that has inspired one significant segment in the dance and clearly brings to mind recent demonstrations across the country as protestors, arms aloft, shouted, “Hands up, don’t shoot.”

“I choreographed that piece years before the current demonstrations, but unless audiences read the program, they’re not going to realize that,” Battle said. “It’s going to be very interesting to see how audiences interpret the piece. Jews and African-Americans in the audience may see something very different. They may view the piece either though the eyes of survivors or as a reflection of the current climate of anti-Semitism or racism. The unifying theme is injustice and history repeating itself.”

Battle said that throughout his life he has been deeply affected by learning about the Holocaust, first in a high school history class, and later as an audience member at Whoopi Goldberg’s eponymous 1984 one-woman Broadway show. In it, she tackled a range of characters, including a hard-bitten male junkie who visits the Anne Frank house in Amsterdam, reads the diary, and is transformed in some way by Anne’s innocence and optimism.

“There’s no way that character should feel a connection with Anne and yet he does,” Battle recalled. “My own visit to the Anne Frank house brought back the power of Whoopi’s performance. It also confirmed my own personal connection.”

While “No Longer Silent” is an abstract piece, it’s far less so than Battle’s other works. Similarly, though he’s employed orchestral music in the past, it’s rarely been as eclectic and complex as the Schulhoff piece and, most significantly, historic events have not served as the basis for the company’s choreography, with one notable exception, “Odetta,” a piece Battle recently commissioned about civil rights activist, singer and songwriter Odetta Holmes.

Both “Odetta” and now “No Longer Silent” represent the company’s new and intensified interest in outreach and education. “In an era of social unrest these pieces are especially timely,” Battle said. “Also, they go back to the roots of modern dance, which has always been very concerned with social justice issues.”

Asked what he’d like audiences to think or feel after viewing “No Longer Silent,” Battle says, “When someone comes up to me after a performance and says it made him feel or see something totally unexpected, something I never even thought about, that’s a great response. That’s what I like to hear.”

Simi Horwitz won a Simon Rockower award from the American Jewish Press Association for her 2014 Forward article, ‘Jewish Enviro-Artists Have the Whole World in Their Hands.’

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO