The Secret Jewish History of Prince

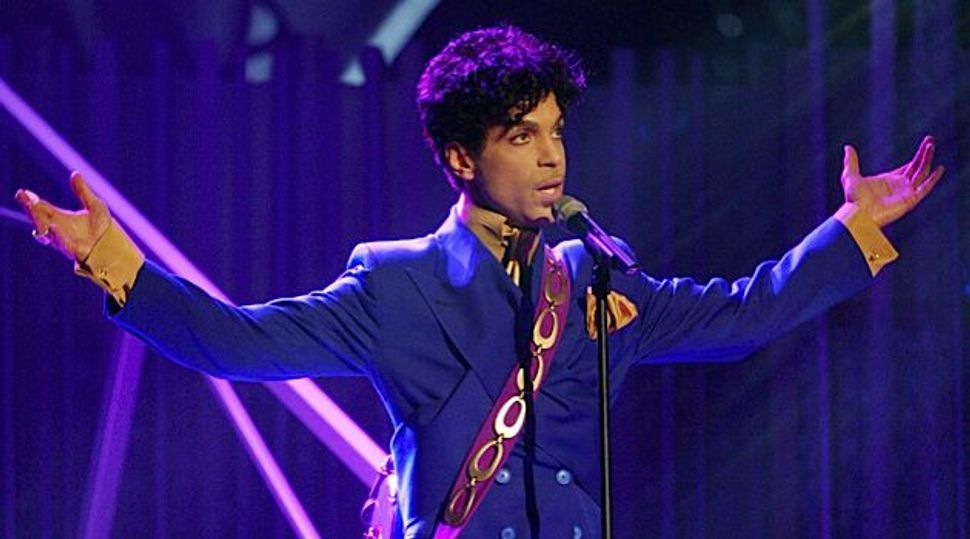

Purple Fame: Prince collaborated with artists from the Jewish section of Minneapolis. Image by Getty Images

Prince died at the age of 57 on April 21, 2016. In honor of what would have been his 60th birthday, we’re re-reading this very Jewish appreciation.

In 1993, at the height of his fame, after selling millions of albums, collecting a closetful of Grammy, Golden Globe and Academy awards, and establishing himself as one of the all-time greats of rock ’n’ roll, Prince did an odd thing: He changed his name to an unpronounceable glyph.

Changing one’s name, of course, has a long and venerable history, going back at least as far as biblical times, and often reflects inner or outer turmoil, such as when Abram and Jacob became Abraham and Israel. In Prince’s case, replacing his name with what he called the “love symbol” — something approximating a union of the symbols for male and female, but not quite — was meant as a protest against the executives at his label, Warner Records, with whom he was struggling for creative and financial control of his career. Imagine you were one of those record label honchos — how infuriating it would be for your biggest star and cash cow to refuse to allow his recordings to bear his name, or any name! Prince — or at this point, “the Artist Formerly Known as Prince” — even began writing the word “slave” on his cheek whenever going out in public.

For the man born Prince Rogers Nelson, this was ultimately an act of self-emancipation; indeed, he titled an album “Emancipation” in 1996. A year earlier, his offshoot band, the New Power Generation, released an album called “Exodus.” Also in 1996, Prince released an album called [“Chaos and Disorder,”][1] a loose translation of two key words in the second verse of the Bible — “the earth was tohu v’vohu” — probably a good description of what it felt like to be sitting in a marketing meeting at Warner trying to figure out how to promote the star’s next album without using the name “Prince.”

A decade after his name change, in 2003, Prince found himself at the center of a quieter but no less unusual episode. On Erev Yom Kippur, a Minneapolis woman answered her doorbell to find two gentlemen standing in her doorway: her hometown’s most famous son — whom she recognized instantly — along with Larry Graham, former bassist for Sly and the Family Stone — whom she didn’t recognize. The two offered her pamphlets and asked if they could come inside to talk about the Bible. Prince, it turned out, had become a Jehovah’s Witness.

Prince was no stranger to the Jewish part of town. When he originally put together his band the Revolution — the group that accompanied him on his breakthrough album and subsequent film, “Purple Rain,” which celebrates its 30th anniversary this summer — he made a conscious decision to have a multiracial outfit featuring both men and women. Having come up through the ranks of [Minneapolis][2]’s thriving funk scene, Prince’s ultimate musical goal was always to be a mainstream pop star and not to be consigned to rhythm and blues. The distinguishing characteristic of his music, what probably accounted for its mass appeal, was precisely that it incorporated many styles not often associated with black music, including new wave, heavy metal, synth-pop, psychedelia and even classical — into what came to be called “the Minneapolis sound.”

So when he hired musicians, they included drummer Bobby Z, who was really Robert Rivkin, a nice Jewish boy from the St. Louis Park section of Minneapolis, the same neighborhood that produced other nice Jewish boys including the moviemaking [Coen Brothers][3], comedian and politician Al Franken, New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman, and Peter Himmelman, the Orthodox singer-songwriter son-in-law of Bob Dylan. Prince found Robert Rivkin through his brother, David Rivkin, who worked with Prince as a producer and engineer. Later on, Prince would engage the services of a third brother, film editor Stephen E. Rivkin, on several of his movie projects. The Revolution’s keyboardist, “Doctor” Matthew Fink, also hailed from St. Louis Park. Violinist Novi Novog, who later went on to play with the group Extreme Klezmer Makeover, also contributed her efforts to “Purple Rain” and subsequent Prince recordings.

Around this time Prince began his association with the Melvoin twins, Wendy and Susannah, daughters of famed studio musician and former National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences president, Michael Melvoin. Melvoin, whose family name was originally Mehlworm, had been a member of the famed “Wrecking Crew,” the studio outfit that played on numerous hit albums by the Beach Boys, Barbra Streisand, John Lennon, the Jackson 5, and dozens of others.

Wendy joined the Revolution as a guitarist and played on “Purple Rain,” and Susannah Melvoin signed on as a backup vocalist. Susannah also nearly became the princess of the royal court of the Revolution, one of several women who were engaged to be married to Prince without ultimately tying the knot; she is supposedly the inspiration for the Prince song “Nothing Compares 2 U,” made famous in a hit version by Sinéad O’Connor. The twins’ brother, Jonathan Melvoin, played percussion on Prince’s “Around the World in a Day” album. (He went on to play keyboards with the band Smashing Pumpkins before dying of a heroin overdose in 1996.)

It turned out to be somewhat fortuitous that Prince chose purple to be his identifying color. One might imagine he adopted purple for its association to royalty, which dates back at least as far as King Solomon, who had the artisans of Tyre provide purple fabrics to decorate the Temple. Purple is also a color associated with psychedelia, such as in the Jimi Hendrix song “Purple Haze.” But purple would gain additional resonance for Prince later on — in Nazi Germany, prisoners in concentration camps who were members of “non-conformist” religious groups, such as Jehovah’s Witnesses, were required to wear a purple triangle.

So when you’re cueing up your anniversary edition of “Purple Rain,” do so with the knowledge that half of the band plus the guest violinist on this revolutionary album were Jewish.

Seth Rogovoy is a frequent contributor to the Forward’s arts pages, where he has explored the Jewish affinities of such unlikely subjects as David Bowie, Apple Computers, Cher and Tupac Shakur.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO