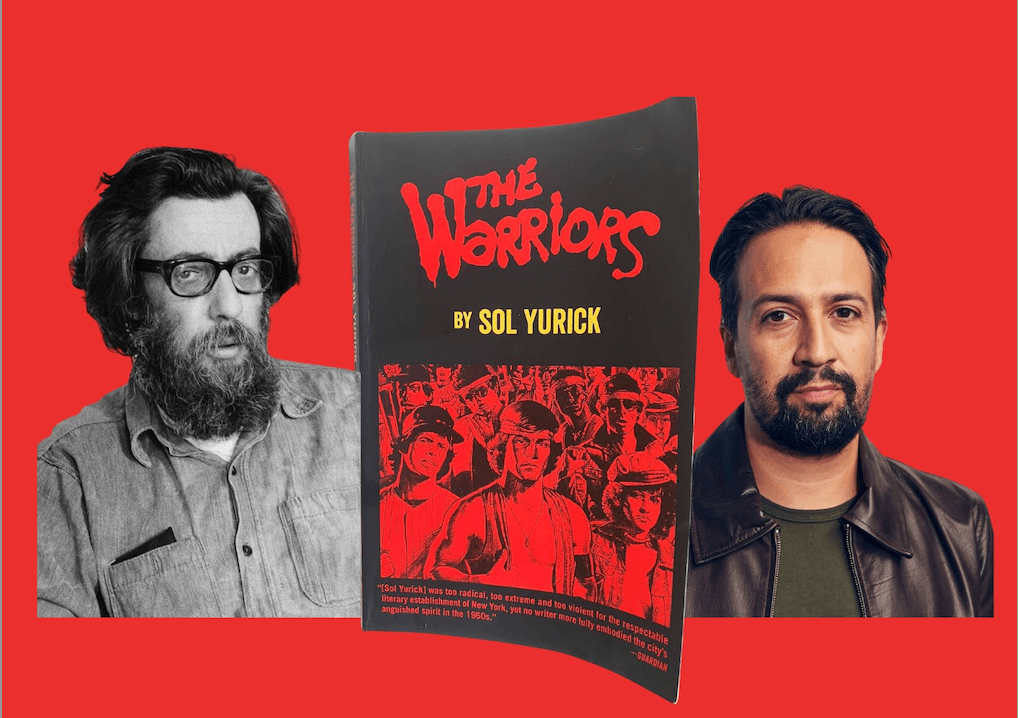

Before ‘The Warriors’ was a cult movie — or a Lin-Manuel Miranda album — it had radical Jewish roots

Sol Yurick, the son of immigrant communists, wrote the novel that was adapted by the ‘Hamilton’ creator

Sol Yurick, who wrote The Warriors, was a native New Yorker and son of immigrants like Lin-Manuel Miranda. Photo-illustration by Canva/© Nancy Crampton/Corey Nickols/Getty Images for IMDb

Among the colorful names in The Warriors, Sol Yurick’s 1965 novel of a gang’s overnight odyssey through New York, one stands out.

Hinton, The Junior, Lunkface and Bimbo tend to blur together, but Mannie Bernstein leaps off the page.

Bernstein is a minor player in Yurick’s saga, based on the homecoming epic Anabasis by the Greek soldier Xenophon. He is a social worker, assigned to keep tabs on a group of juvenile delinquents. He also, like Yurick himself, seems to be Jewish and a close observer of the disadvantaged who are failed by the system time and time again.

Those who are most familiar with The Warriors from Walter Hill’s cult classic 1979 film, or heard about Lin-Manuel Miranda and Eisa Davis’ new concept album based on the material, may not know that Yurick’s original story drew from his own experience as an investigator for New York City’s Department of Welfare, where he encountered families with kids in “fighting gangs.”

“I came in contact with, as it were, the lower social and economic depths,” Yurick, who died in 2013 at the age of 87, wrote in an afterword to a 2003 edition of the book. “I went through a kind of social shock.” But it was far from the first.

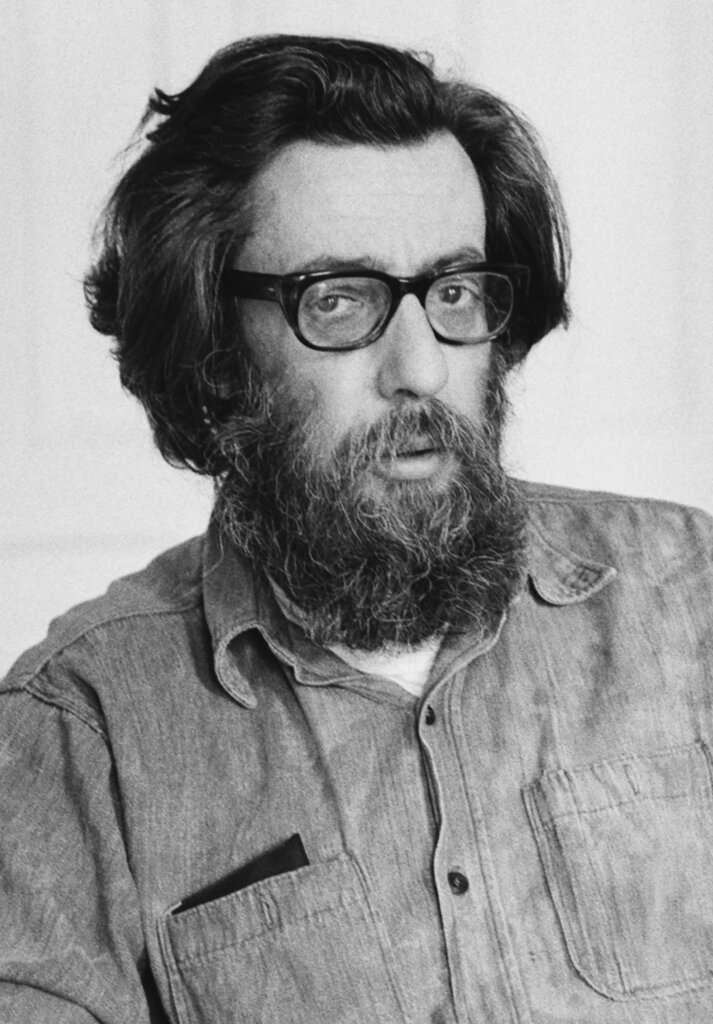

Yurick was born Jan. 18, 1925 to Sam, a milliner from outside Kiev, and Florence, who came from Lithuania, and grew up in the Bronx. Sam and Florence were communists, though they carried no cards, and, during the Depression, were among the first to collect welfare.

“They used to come and look at your cabinets and say, ‘You have food in your refrigerator. I don’t think you need us anymore,’” Yurick’s widow, Adrienne, a potter and ceramics teacher, told me. “Sol was quite the opposite with his clients.”

Yurick’s first language was Yiddish, but on entering kindergarten, he told his mother that if she spoke it to him, he wouldn’t answer.

From the start Yurick’s interests were wide-ranging. One day in elementary school at P.S. 76, he was secretly reading Darwin behind his geography book. When his teacher saw what he was doing, she said, “Of all the monumental gall,” which would later become an inside joke for Yurick and his wife. He was always tall for his age, Adrienne Yurick said, had few friends but was a ravenous reader, who was allowed to use the adult section of the library.

While communism and global revolution were table talk in the Yurick home, Sol broke from his parents in 1939 over the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact, which forged an alliance between the Nazis and the Soviet Union, recalling in a New York Magazine interview that his “feelings as a Jew were more important than my feelings as a communist.”

“He thought he was apolitical for a long time, but he really never was,” Adrienne Yurick said. “Everything he did had a political component.”

Yurick enlisted in the Army out of high school in 1944. In the service, Yurick’s family friend, the writer Samuel Fromartz told me over the phone, he may have first felt a “sense of otherness” being a Jewish kid from New York, a feeling that resonates throughout his work.

Attending New York University on the GI Bill, Yurick studied literature (after false starts in science, psychology and philosophy) and lived in a cold-water flat on Morton Street.

He never could say for sure when he landed on the idea of transposing modern-day gangs onto Xenophon’s classic of mercenary youth, but it was in his head for years before he wrote it, in three weeks, while recovering from 27 rejections for his first novel, Fertig.

Fertig, about a man whose child dies from the negligence of the American medical system and takes revenge, was written for Yurick’s master’s thesis at Brooklyn College. The Warriors, which Yurick called his potboiler, came out first.

If you only know the movie, you might be surprised by the extreme, unflinching, even casual violence of Yurick’s book.

His main warriors, the Coney Island Dominators, who are Black and Latino, reflect not just territorial divisions, but ethnic ones. They come from dysfunctional households, and so find surrogate families within their hierarchy. They murder a bystander, commit two gang rapes and patronize sex workers in Times Square bathrooms. Yurick manages to make these criminal youths somewhat sympathetic by presenting a city whose lawful side is no better, and whose racist cops are eager to brutalize them.

“Coming from a communist background and being a Jew added to my sense of alienation from American life,” Yurick wrote. “These social and economic traumas had become part of my unconscious. To me, being a writer was like being a rebel. I’ll show you what your world is really like, I must have thought. And what of the gangs? Theirs, too, was a form of revolt. Some gangs take to the streets; some gangs emerge in October 1917.”

The author said that this “revolutionary content was missing” from Hill’s film, which he publicly regarded with disdain.

“I looked for my novel on the screen; I found the skeleton of it intact,” he wrote. (His daughter, Susanna, then around 11, assured him kids would love it — and they did, perhaps too much, with various cities fearing the film’s influence on the youth.)

By 1979, when Hill’s novel prompted a reissue of The Warriors, Yurick had moved beyond the Anabasis, publishing The Bag, a scathing story featuring a slumlord Holocaust survivor and a novelist earning a living working at the welfare department, as well as the short story collection Someone Just Like You. The works were righteously angry, prompting one critic to write “there is more brutality in his tale of a beating than the beaten feels.”

But at home in Park Slope, where he held court, rangy and sporting an almost rabbinical beard, rolling his own cigarettes and drinking coffee, a beloved cat or three nearby, Yurick was funny, and people came to listen as he riffed from one subject to the next.

Fromartz, whose mother worked with Adrienne at the Woodward School in Clinton Hill, spent many days around Yurick’s kitchen table as a teenager. He said Yurick seemed to espouse “radical ideas” but wasn’t an ideologue. He’d say something provocative, but build on it, connecting metaphysics and information technology to the ancients. His last novel, before a pivot to long, tangential, but deeply learned essays, was 1981’s Richard A. which made bold predictions about man’s relationship with technology.

Adrienne Yurick found the book cold, but undeniably prescient. “We’ll see if people have sex with their machines and don’t need people at all anymore,” she said.

The track record of Yurick adaptations — or at least faithful ones — is not great. Hill’s film airbrushes the plot of The Warriors with a layer of camp and strips away much of its social commentary. The Alec Baldwin vehicle The Confession, based on Fertig, turns the novel’s act of tormented vengeance into a morality play. But what would Yurick make of Lin-Manuel Miranda’s concept album, which the family was told would work from the book, not the film?

Fromartz said that it’s possible that Yurick, who mixed comic books and sociology with ancient Greek history, would appreciate Hamilton, which remixes the founding fathers with hip-hop and R&B.

“He would probably have some issue with the politics of it, which he often did in anything in popular culture,” Fromartz said.

Adrienne Yurick says that she doesn’t think he’d be a huge fan of Hamilton, but can’t say for sure what he’d think of Miranda adapting The Warriors, other than that he’d likely agree to it. “I think he would have been very dubious,” she said.

But it’s no wonder why Miranda might be attracted to the property. Yurick thought musicals like West Side Story and later Paul Simon’s The Capeman took liberties with the reality of gang dynamics, but at least Bernstein’s play proved a massive success. Miranda, who is of Puerto Rican descent, has a personal connection to West Side Story, having provided Spanish lyrics and dialogue for a 2009 Broadway revival and Steven Spielberg’s film adaptation.

Miranda, a native New Yorker whose signature style blends different genres of music, might see the theatrical potential in Yurick’s book, whose ethnic gangs could each provide their own multilingual soundtrack, from the Boogie Down Bronx’s Nuyoricans down to the carnival atmosphere of Coney Island, the Dominators’ home turf. “There was something subversive about the gangs,” Yurick wrote, “especially about the music that they loved,” rock ‘n’roll.

But when one hears Yurick discuss his work, there is a subtler dimension at play that may have piqued Miranda’s interest.

In a 1979 WNYC radio interview, addressing the xenophobia and territoriality explored in his story, Yurick said that, researching these gangs, he discovered that “every single device that you find in international diplomacy, in military strategy, is used by the kids.”

Miranda, who brought rap battles to George Washington’s cabinet meetings, likely found an affinity here. But Miranda, whose greatest protagonist “wrote his way out” of his dilemmas and who used Hamilton’s biography to advocate for immigrants and the disenfranchised, also may have found something in Yurick, a son of politically active immigrants, and his approach to advocacy.

“His work was what he contributed. He was not an activist, you know,” Adrienne Yurick said. “But he wrote.”

Correction: A previous version of this article misstated that Yurick grew up in Co-op City in the Bronx.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO