Just how accurate is the Peacock series ‘The Tattooist of Auschwitz?’

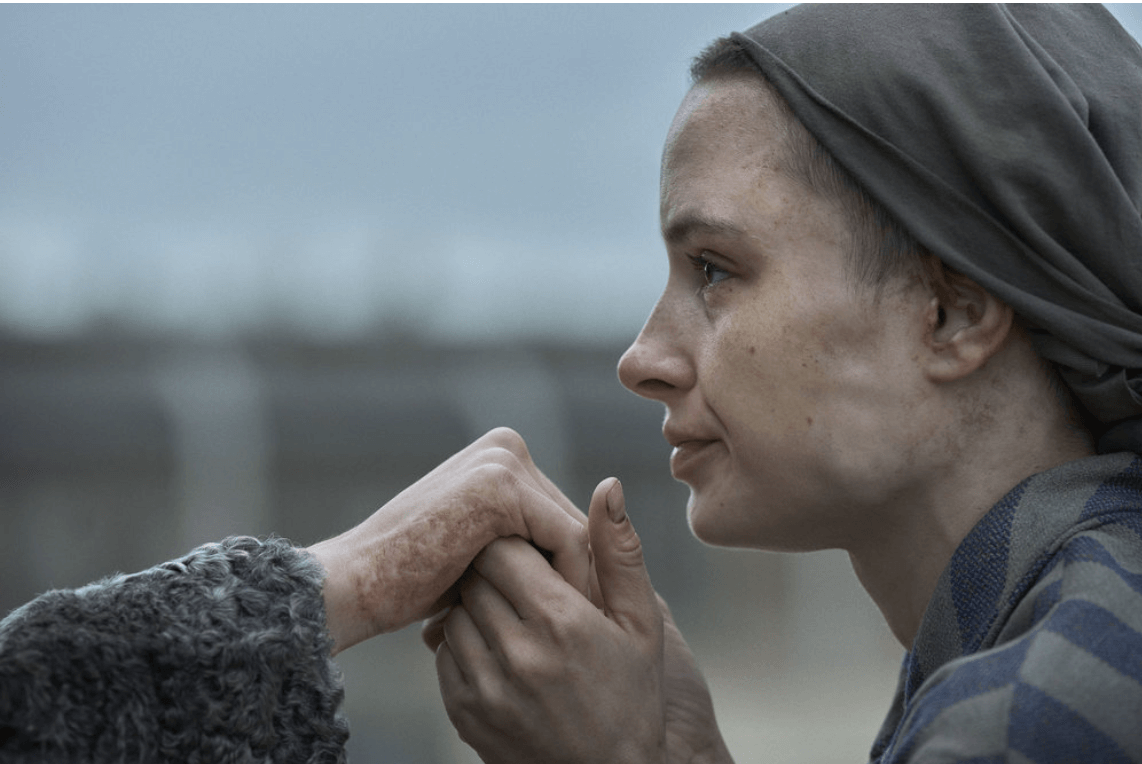

Anna Próchniak as Gita Furman. Photo by Martin Mlaka/Sky UK

At the end of the first episode of The Tattooist of Auschwitz, a new Peacock limited series based on the book of the same name, Lali, a Jewish prisoner, is forced to tattoo the prisoner Gita Furman. The two instantly fall in love.

This dark twist on the meet-cute is a pivotal moment in the series inspired by the true story of two Slovakian Jewish survivors of Auschwitz-Birkenau: Lali, played by Jonah Haur-King, and Gita, played by Anna Próchniak. It’s the poetic core of the story; the moment a prisoner is dehumanized into a number becomes a life-changing human connection. The two married after the war and eventually settled in Melbourne, Australia.

But I was most interested in the tattoo scene, a brightly lit moment in a dark hell, because I was waiting to see whether the number tattooed would be: “34902” or “4562.”

In Heather Morris’s 2018 International bestselling book, the number is “34902.” However, according to Gita and Lali’s son Gary Sokolov and the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, the actual number was “4562.” Morris is a New Zealander living in Melbourne who interviewed Lali Sokolov (nee Eisenberg) over three years before his death in 2006.

It is just one of several basic details, like the spelling of Lali’s name, which Morris got wrong and caused a stir in 2018. She clarified to The New York Times that the novel was never intended to be non-fiction—even though a publisher’s note in an early edition stated, “every reasonable attempt to verify the facts against available documentation has been made.” In 2007, Morris included some of the same inaccuracies in a Guardian obituary of Lali.

The Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum followed up with an extensive fact check, stating that “the book contains numerous errors and information inconsistent with the facts, as well as exaggerations, misinterpretations, and understatements.” The museum concluded that “The Tattooist of Auschwitz cannot be recommended as a valuable position for those who wish to understand the history of the camp.”

The discouraging report didn’t affect sales. By 2019, the book had been translated into 47 languages, feeding a public hungry for inspiring novels set in the most famous concentration camp. It’s the most successful of a booming sub-genre: Recent titles include The Midwife of Auschwitz, The Dressmakers of Auschwitz, The Seamstress of Auschwitz, The Librarian of Auschwitz, The Mistress of Auschwitz, The Stable Boy of Auschwitz, and The Magician of Auschwitz.

Books and movies that turn tragedy into entertainment may not meet the standards of historians. Still, at a time when knowledge of the horrors of the camps have been decreasing, they have become, for many, the main form of exposure to the Holocaust.

Claire Mundell, the series’ executive producer, says she hopes interest in the true story of Lali and Gita can spur Holocaust education. “I hope that the experience of watching the show motivates a broad audience to go and learn more,” the Scottish producer told me over Zoom.

Mundell optioned the rights to the book in 2018 and met with the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum. “We committed to them that we would work through those comments and address whatever we could,” she said.

Mundell teamed up with the Israeli director Tali Shalom-Ezer, whose grandfather survived Auschwitz. Morris came on as a consultant. Their guiding principle was to focus on what Lali himself had said. “We believe the survivor,” Mundell told me.

They used the correct prisoner number for Gita (“4562”), but other decisions were not so simple. The nearly 3-hour testimony that Lali gave to the USC Shoah Foundation in 1996 makes clear that he is the source of many of the claims doubted by the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum. It’s Lali who said that women prisoners smuggled gunpowder under their nails to saboteurs and he who described the soccer matches between Nazi SS men and prisoners

In the book, Lali visits a gas chamber. “I bet you’re the only Jew who ever walked into an oven and then walked back out of it,” his SS boss Stefan Baretzki told him. The museum researcher suggested Morris borrowed this scene from Hollywood movies. But Lali recounted the story with certainty in his testimony: “Only one guy who was in the crematorium came out of the crematorium, and that was me.

The elderly survivor sounds lucid, but he also forgets names and misremembered the year his son was born. “He did several testimonies,” Mundell told me, which made her work complicated. “If you look at survivors’ testimonies, many times, they will contradict each other,” she said.

But if Lali’s story is out of the ordinary, it is for a reason. “What I can tell,” he said to the interviewer, “No one can tell.” He then explains why: “I was close with the top brass of the SS.”

Female prisoners who sorted through new prisoners’ clothes would give Lali the money, gold, and diamonds they found. He would trade these with Polish workers for black market goods sought after by both the prisoners and the Nazi guards. Lali gave the SS men luxury items like fur coats and necessities hard to find during the war, like a steady gas supply for their motorcycles. “They helped me a little bit,” explained Lali, “I gave them something.”

These small favors kept Lali and Gita alive. Central to their survival was the SS man Baretzki, who Lali said killed 20 to 30 prisoners a day but who he considered a “friend.”

Morris’ book doesn’t question Lali’s recollections and minimizes moral questions about befriending SS men; Mundell tackles these issues. Any adaptation of a book to television means storylines are condensed to fit between commercial breaks, and individuals are combined into composite characters, but Mundell adds scenes of an older Lali, played by Harvey Keitel, telling his story to Morris after Gita’s death in 2003.

Keitel masterfully takes on the mannerisms and pattern of speech of an older Lali, bringing the story into the present era. These sunny Australian scenes break up the dark gloom of Auschwitz-Birkenau, which can be hard to watch with their mini-portraits of anonymous victims of the Nazi’s mass violence.

“We wanted to create a narrative approach which honors the nature of memory and trauma,” Mundell explained.

The older Lali remembers and then re-remembers. He is haunted by visions of his SS boss and friend Baretzki, who is a constant reminder of the cruelty of Auschwitz and the difficult decisions Lali was forced to make, albeit at times, these moral dilemmas sometimes still feel understated. Morris, a social worker by training, patiently listens to and comforts her new friend.

While Lali promises in the first episode that “this is a love story,” what develops over six episodes is something darker and more complex. Lali and Gita’s relationship is the center of the series. It drives their fight for survival, but the unequal friendship of Lali and Baretzki is more thoroughly examined in the series than in the book.

It creates a more complex story — one that defies the “happily ever after” one expects.

“They have done an absolutely amazing and brilliant job with my parents’ story,” Gary Sokolov wrote in an email.

But perhaps most crucially, the series has already won the most important Jewish seal of approval of all. It ends with a new song sung by Barbara Streisand.

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and the protests on college campuses.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

Make a gift of any size and become a Forward member today. You’ll support our mission to tell the American Jewish story fully and fairly.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Join our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.