In ‘Vishniac,’ a portrait of a scientist, a fabulist and a chronicler of a disappearing world

Laura Bialis’ documentary shares the work and life of a photographer who captured Jewish Europe before the Holocaust

Philipp Mogilnitskiy as Roman Vishniac in Laura Bialis’ Vishniac. Photo by Anna Wloch

Do you know about the Spielberg-produced film about a loving but troubled family led by a workaholic scientist and a dreamer who brings home a pet monkey?

No, not The Fabelmans, but the similarities may partially explain why Nancy Spielberg (who uses the same monkey actor from her brother’s film) was eager to work on Vishniac, a documentary about photographer Roman Vishniac, a versatile creative who embodied many of the Spielberg family’s own qualities. It helps, perhaps, that Vishniac’s photos were used as a visual reference for Schindler’s List.

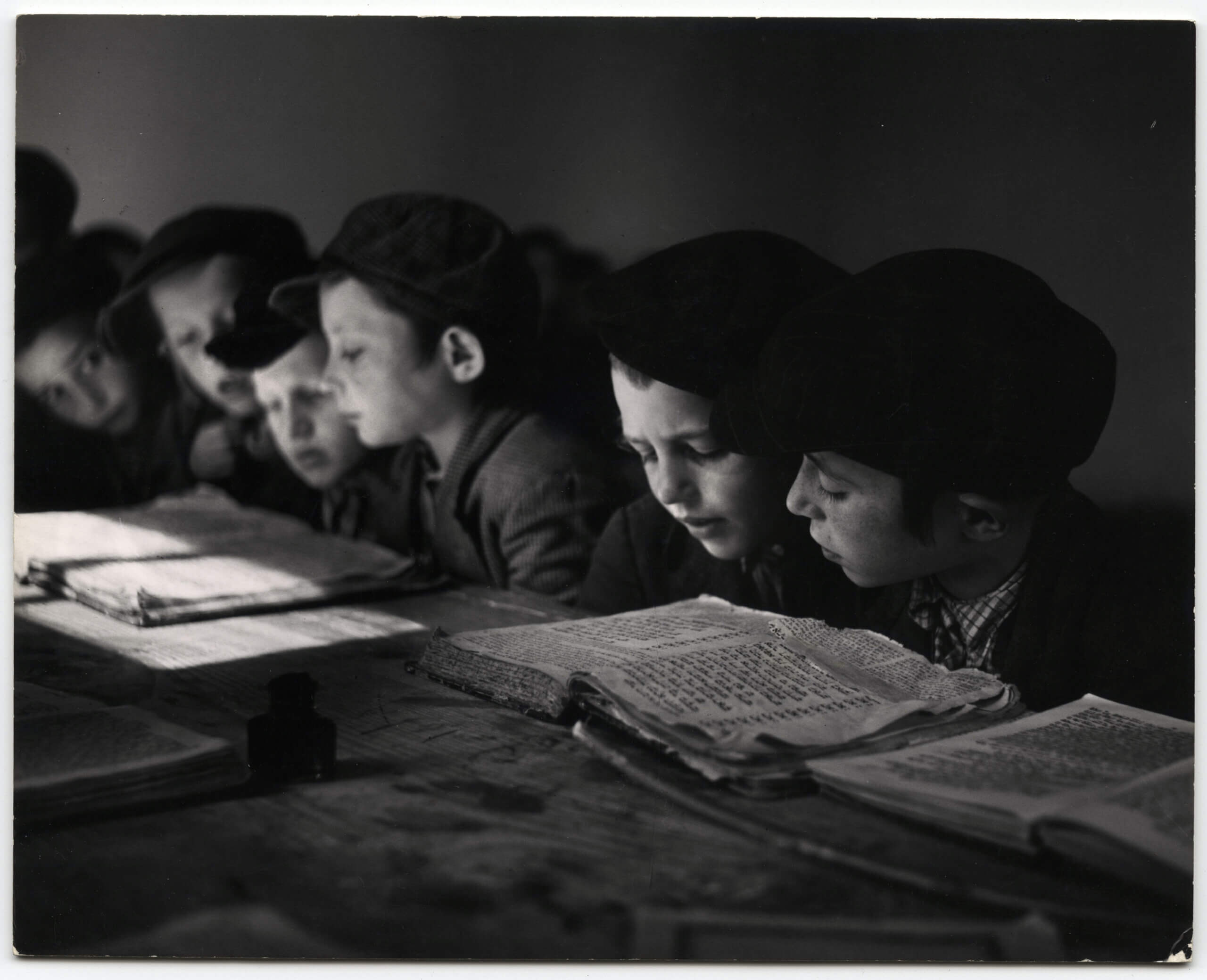

Vishniac, celebrated for his images of microscopic organisms and European Jewish life, had an amazing gift for storytelling through pictures. He also had a deep love of his fellow Jews that, in the years before World War II, brought us some of the most iconic images of a people on the edge of the grave.

Directed by documentary filmmaker Laura Bialis (Refusenik and Rock in the Red Zone), Vishniac begins with a dramatization of the photographer’s daughter, Mara, sitting in his darkroom as a child and watching faces take shape in the developing tray.

“I would ask him about the people in the pictures,” said Mara Vishniac Kohn, who Bialis interviewed before her death in 2018, “and he would say things like, ‘that’s our family. These are our people.’”

Vishniac, we learn, was inclined toward fabulism, but in this case the fib was in a larger sense true.

Born in Moscow to a prosperous family who escaped the Pale of Settlement, Vishniac was not directly related to many of his subjects, whom he filmed over years in cities like Warsaw and Lublin and far-flung shtetls and mountain villages. Vishniac had money and was well-assimilated. But there is no denying that when one looks at a Vishniac photo, of children in cheder, of bearded rebbes, old men and women pushing carts or city-dwelling Zionists preparing for an agricultural life in Palestine, that he forged a connection with them as a fellow Jew. The people in the pictures gaze back at you, dissolving any sense of distance.

“I would submerge myself in the suffering of my people, eat what they could afford, sleep in the same bed, learn their problems,” Vishniac vowed. He was on assignment from the Joint Distribution Committee (and the Forverts, under the direction of editor Ab Cahan) to capture Jewish life and inspire donations for relief efforts.

With the rise of Hitler in his adopted home of Berlin, Vishniac put his playful modernism and microscopic critters to the side. Still, his love of beauty — be it in protozoa or photos of his lover, and later wife, Edith — is unmistakable and his composition makes the poignancy of his pre-war photos of the shtetl all the more pronounced.

Bialis’ film is not just about Roman, who we learn had an unhappy marriage with his first wife, Luta, and unfairly favored his son, Wolf, who was a gifted scientist. Speaking with Mara and Vishniac’s grandchildren, the documentary tells a larger story about antisemitism, American immigration and the toll the photographer’s self-mythologizing took on the family.

“He regarded himself as a mixture of Moses and Superman,” Vishniac Kohn says.

While responsible for innovations in the practice of photomicroscopy, Vishniac was not a rigorous scientist, a fact that frustrated Wolf, who became a respected microbiologist (a crater on Mars is named for him). Talking heads from the world of photography and Jewish history speak to Vishniac’s genius for narrative. And while his camera didn’t lie exactly, Vishniac often embellished what was in the frame, sometimes to the benefit of the bigger picture. Scholar and curator Maya Benton found that Vishniac may have staged some of his images, but the film doesn’t address that, nor does it engage with Vishniac’s Eastern European contemporaries, like Yiddishist Menachem Kipnis, who included elements of modernity in their work and likely produced a truer image of pre-Holocaust Jewry.

Bialis’ slick dramatizations of Vishniac’s life, while tastefully done, are underwhelming when paired with the immediacy of the photographer’s own images. But in chipping away at some of Vishniac’s own legend — he did not, as he claimed, snap Albert Einstein the moment he created the atom bomb — the potency of what his work stands in for still carries through.

Among the most moving moments in the documentary is an interview with the granddaughter of a farmer Vishniac met and filmed in the remote farming village of Apsha.

“There’s no oral history of our family, there’s no tablecloth, there’s no candlesticks — there’s nothing,” the granddaughter says. All that remains is the picture.

For many Jews who lost too much, Vishniac’s photography is a testimony to the lives their relatives lived. They may not be one’s actual family, but they are undoubtedly one’s people.

Vishniac premieres Jan. 16 at the New York Jewish Film Festival followed by a run at the Quad cinema. A full list of screenings can be found here.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO