Netflix’s ‘Russian Doll’ features a Hungarian ‘Gold Train’ filled with Nazi loot. What’s the real story?

The Hungarian Gold Train has taken on mythical proportions, but its reality is in some ways as mind-bending as the plot of Natasha Lyonne’s show.

Nadia Vulvokov (Natasha Lyonne) and her friend Maxine (Greta Lee) encounter the grave of a Hungarian priest who saved Jews during the Holocaust, in Season 2 of “Russian Doll.” (Netflix)

(JTA) — When Season 2 of “Russian Doll,” Natasha Lyonne’s sci-fi exploration of identity and trauma, dropped on Netflix Friday, it immediately became clear that teasers of the season’s Jewish content were not overblown.

In the season, which features New York City subway-induced time travel, Lyonne’s character zips back to 1982, the year of her birth; 1968 New York City; and 1944, when her grandmother was being pursued by Nazis in her native Budapest. In every timeline, she witnesses how layers of Jewish trauma forged the family in which she experienced a difficult upbringing.

The Budapest storyline centers around the theft of the family’s wealth by the Nazis, and Lyonne’s character, Nadia Vulvokov, finds herself seeking to safeguard valuables that are destined for what came to be known as the Hungarian Gold Train.

That train has taken on mythical proportions in storytelling about the Holocaust, but its reality is in some ways as mind-bending as the plot of “Russian Doll.”

The train was filled with art, silver and other valuables stolen by the Nazis from Hungarian Jews, then pillaged again by American forces after the war. In a rare case where appropriated wealth could potentially have been returned to survivors, that did not happen.

In the years before World War II, Hungarian Jews were wealthy and successful, making up a quarter of university students and a majority of large business owners despite being only about 6% of the country’s population. Antisemitic laws by the Hungarian government in the late 1930s and early 1940s restricted Jews’ access to certain professions and limited their ownership of industry, but many had accumulated great wealth already. As the Nazis murdered Jews across the continent, Hungarian Jews continued to live largely as they had — with trepidation and amid frightening antisemitism, but in their own homes, surrounded by their belongings.

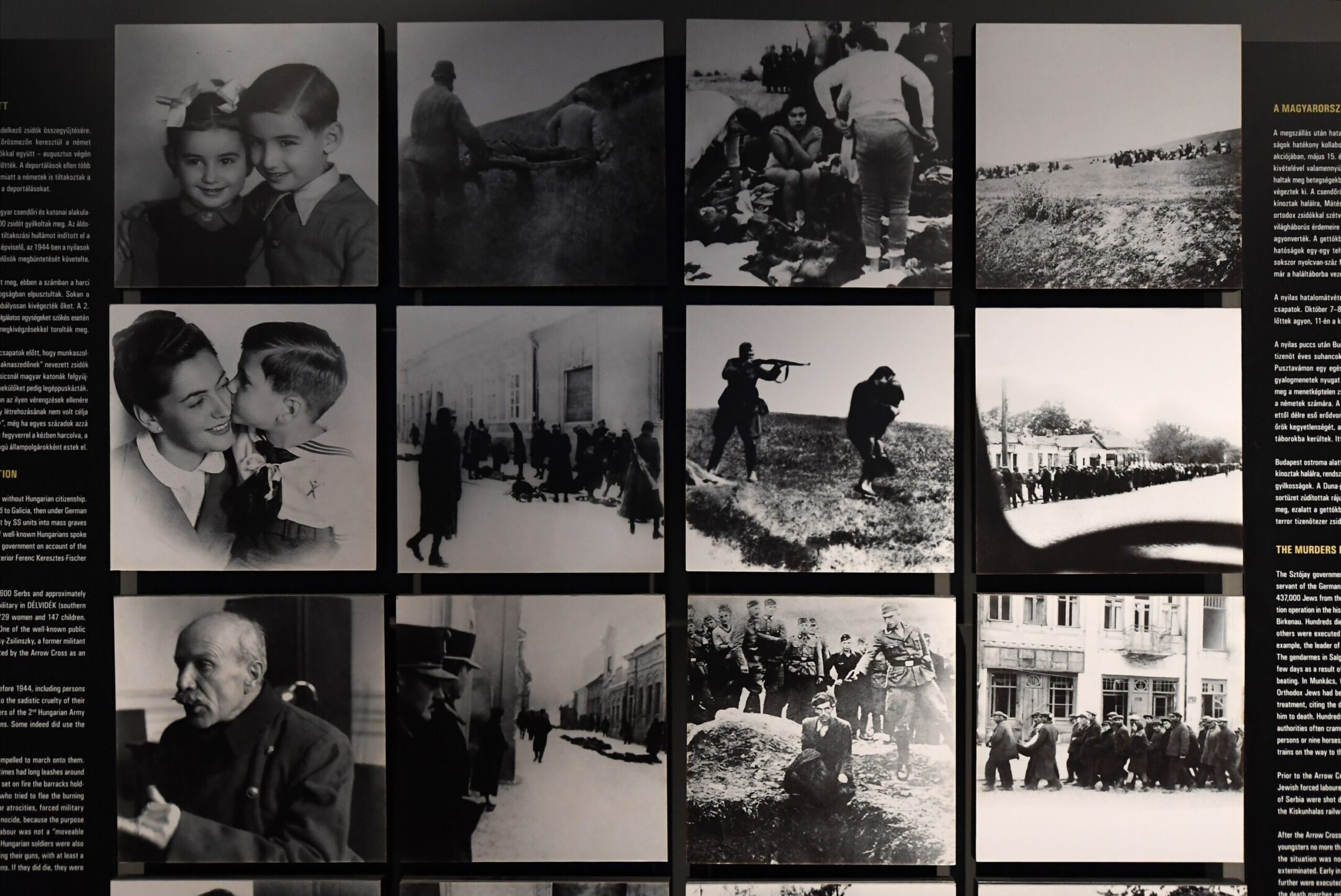

Historical pictures view at the Holocaust Memorial Center in Budapest, 2019. (Attila Kisbenedek/AFP via Getty Images)

That changed in early 1944, when the Nazis finally invaded Hungary and enacted their genocidal campaign of the Jewish population, estimated at about 825,000 at the time. As they dispatched trainload after trainload of Jews to Auschwitz, the Nazis (with the support of their local collaborators) collected and carefully cataloged the belongings they ordered the people they would murder to hand over.

Nadia discovers a receipt, inked in script on a piece of pink paper, for the items taken from the Peschauer family, her grandmother’s. The items, she reads from the list, are contained in lot 1407, enabling her to locate and reappropriate them during one of her jaunts to 1944.

Nadia finds the items, which appear to include Shabbat candlesticks, in a massive warehouse where a soldier invites her to “shop” for new clothing. There, she asks two other women perusing the goods where the lot numbers are displayed.

“Have you seen any numbers on this stuff?” she asks. “There should be parcel numbers. They told the families they’d keep all their things together.”

“Why does it matter to you?” one of the women responds, with suspicion. Thinking quickly, Nadia responds, “I just want to make sure I’m getting a full set.” She ultimately finds the box with her family’s belongings and spirits them into a hiding spot where her grandmother can retrieve them after the war.

Nadia Vulvokov (Natasha Lyonne) pries open a crate containing her family’s belongings that were seized by the Nazis in Season 2 of “Russian Doll.” (Netflix)

In reality, the stolen goods were loaded into a train and sent out of the country in the war’s waning days, as Soviet forces approached. American soldiers seized it in May 1945 in Werfen, Austria.

Over the next year, the United States would enter into two international agreements about how to handle property appropriated during World War II. Such property, according to the treaties, should be returned to the people from which it was taken when possible, and to the countries from which it was stolen if individual ownership could not be determined.

Hungarian survivors and the organized Jewish community they reconstituted in the wake of the war, after which the majority of Hungarian Jews had been murdered, argued that the goods on the train could indeed be returned to their owners. But that did not happen — even as negotiations over the contents of the train began quickly.

In 1946, Hungarian officials pressed American officials to return the contents of the train. But by the beginning of the next year, arguing that identifying owners would be impossible, the Americans made clear that they planned to allow the valuables to be sold at auction to benefit war refugees. (Some of the valuables had already been requisitioned for U.S. Army officers’ use, later evidence revealed. Meanwhile, French authorities agreed to restore to Hungarian Jews several train cars of valuables found in territory they controlled.)

“The U.S. Government is preparing to turn over to the Intergovernmental Committee on Refugees the contents of the so-called Hungarian gold train, captured in Austria, which consists mainly of valuables stripped from Hungarian Jews, it was learned here today,” the Jewish Telegraphic Agency reported from Washington, D.C., in January 1947. “A formal announcement to that effect will be made by the State Department within a few days.”

The following month, JTA reported confirmation of the plan by the director of the Intergovernmental Committee on Refugees. The report from Feb. 16, 1947, used the phrase “Hungarian ‘gold train.’”

The director “said that the contents of the train are valued at approximately $15,000,000 and that American military authorities were still cataloging the valuables, which include furs, rugs, household linens, clocks, watches, and jewelry,” JTA’s report said. “The non-monetary gold is stored in the vaults of a bank in Frankfurt, while the remainder of the loot is in Salzburg.”

Hungarian Jews protested the plan. And 50 years later, the restitution of goods stolen from Jews by Nazis remained a focus of international diplomacy in the region. The U.S. ambassodor to the European Union, Stuart Eizenstat, traveled to Eastern Europe, including Hungary, in 1995 to press governments there to provide restitution to Holocaust survivors and the descendants of victims.

Four years later, Eizenstat was on a commission formed by President Bill Clinton to investigate the fate of the Hungarian gold train that concluded that American forces had looted the valuables, preventing them from being restored to their rightful owners.

“I think we knew when this commission was set up there would be some dark spots on our own record,” Eizenstat, then the U.S. deputy treasury secretary, told JTA in 1999, when the commission’s findings were released. At the time, analysts suggested that the original contents of the train could have been valued in contemporary dollars at $2 billion.

The findings were viewed as a potential template for other countries to examine the dark spots in their postwar history. It also resulted in work for U.S. authorities, who said Americans would undertake a “search for individual claims made by Hungarian victims and try to determine if survivors or their heirs have also made efforts to regain their property.”

Ultimately, a restitution pact signed in 1995 began issuing payments in 1997, more than 50 years after the Nazis demolished prewar Hungarian Jewry. Survivors living in Hungary received monthly pensions of about $40 each. The initiative was not limited to people whose family belongings were on the Gold Train. A number of survivors sued the U.S. government, claiming the pact undervalued their losses. They settled in 2005 in a deal that provided for needy survivors.

Holocaust memorial in the shape of a weeping willow tree, erected in 1990 in back of the Dohany Street Synagogue in Budapest. (Ruth Ellen Gruber)

The Gold Train is far from the only intersection with real-life Hungarian Holocaust history in “Russian Doll.” Nadia travels (by airplane, not time travel) to present-day Budapest, finding her family’s apartment building on Dohany Street and locating a plaque noting the names of the Jewish families that lived there prior to the Holocaust. The Dohany Street Synagogue is the largest in Europe; it’s also the site of a mass grave from 1944, when the area was briefly turned into a ghetto by the Nazis.

In Budapest, Nadia tracks down the grandson of the Nazi guard who issued the receipt for the family’s belongings. He at first denies knowledge of his family’s Nazi history, then is found to have unearthed evidence of it after his father died.

“I clean out his house and I find my grandfather’s things — papers, medals, some clothes,” the grandson says, in a comment that encapsulates Eastern European ambivalence over reckoning with the role that locals played in the Nazi project. “What am I meant to do? As far as I can tell, he was a deeply boring and awful man.”

Later, Nadia winds up in a cemetery, where she spots an Orthodox Jew visiting a grave. The grave is of Kiss Laszlo, a priest whose headstone is covered with small stones. “What’s with the rocks?” Nadia’s friend asks her. “It’s a Jewish thing,” she answers. “A sign of respect. You know, like in ‘Schindler’s List.’”

Nadia Vulvokov (Natasha Lyonne) visits a priest, Kiss Laszlo, during a visit to 1944 Budapest. (Courtesy of Netflix)

The priest plays a pivotal role in enabling Nadia’s grandmother to retrieve her belongings, and it is clear that he is memorialized by local Jews because of his efforts to help them during the Holocaust. He is not a real figure, although 876 Hungarians are recognized by Yad Vashem, Israel’s Holocaust memorial and museum, as “righteous among the nations” for their efforts to save Jews. Dozens are named Laszlo, a common Hungarian first name, and several have the surname Kiss.

Laszlo Kiss, in fact, was the name of a Hungarian Jew who survived Auschwitz and spent the last decade of his life teaching about the Holocaust in and around Budapest, where he worked as a chemistry professor. Kiss died in January at 94, just shy of 80 years after the Nazis murdered his entire family, including his twin brother.

In “Russian Doll,” Nadia’s grandmother makes it to the United States, along with a friend from the Hungarian Romani minority, also persecuted by the Nazis. There, the wealth retrieved from the warehouse that would later wind up on the Gold Train became a weight that repeatedly holds the family back — while also becoming a pivotal plot point in Season 1.

“I didn’t do all of this just to end up with the same fucking Krugerrands,” Nadia says in 1968 New York City, referring to the gold coins she was being offered in exchange for the retrieved items.

The real story of the Hungarian Gold Train has fueled mythology about other caches of Nazi-siezed goods that have so far not been verified. Treasure hunters trawl Eastern Europe looking for tunnels that they believe contain trains filled with valuables, as detailed in Menachem Kaiser’s 2021 book “Plunder.”

In Poland in 2015, two men said they’d found such a train but refused to share its location until they were promised a cut of the findings. A Polish government official said he thought the find was authentic, but it was later ruled a hoax.

This story originally appeared on JTA.org.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO