‘Stavisky’ Remains A Slick Study Of Jewish Identity

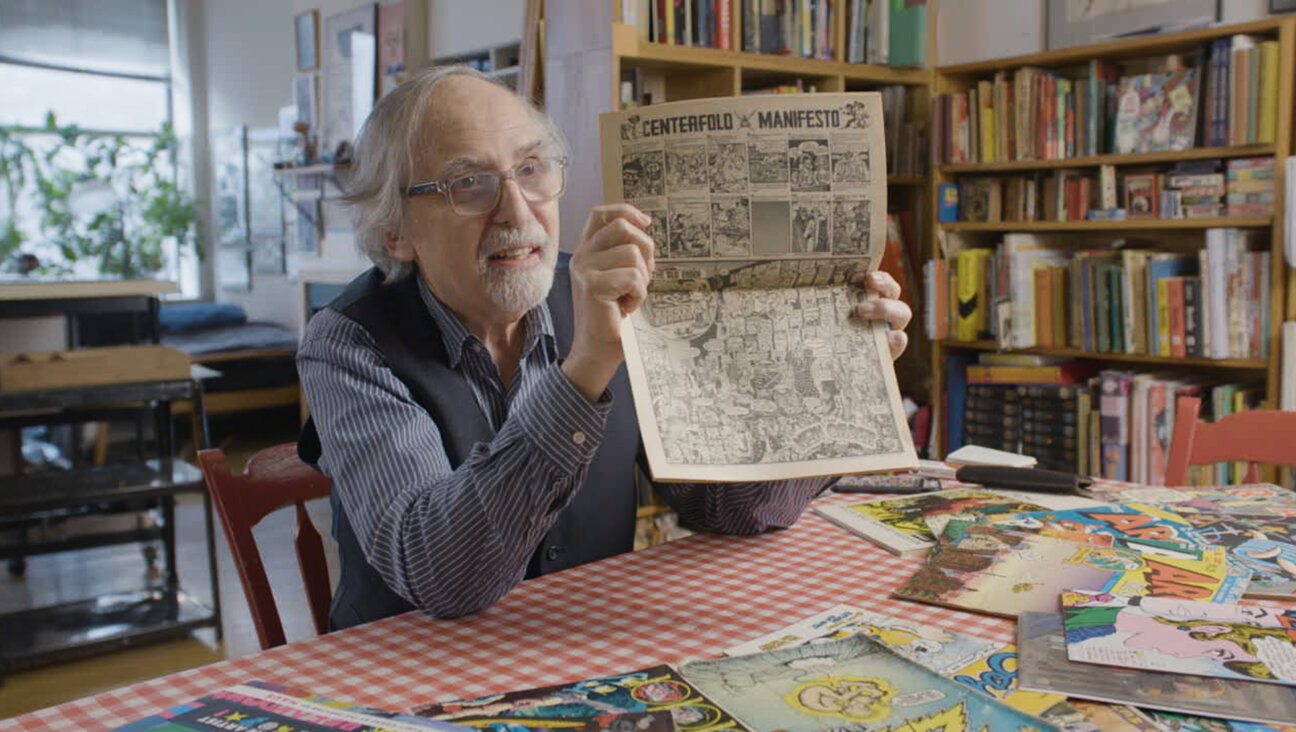

Jean-Paul Belmondo in Alain Resnais’ STAVISKY (1974). Playing Wednesday, October 3 through Thursday, October 11. Image by Courtesy of Film Forum

American audiences may not be familiar with the name “Serge Alexandre Stavisky” or his many aliases, but the French recognize the Russian-born Jewish con man’s decline as helping ease their country’s slide into Fascism.

A new restoration of director Alain Resnais’ 1974 film “Stavisky” opens Wednesday at New York’s Film Forum and plays through October 11 as part of a retrospective of the work of screenwriter Jorge Semprún. The film, Resnais’ first period piece, played off his lifelong fascination with the figure of Stavisky, whom he encountered in his youth in vivid illustrations in broadsheets and as a wax figure at a museum. Resnais knew him only in sensationalist reproductions, and aimed to mimic these replicas’ effects over verisimilitude.

But perhaps the most surprising aspect of the film, lavishly produced in Art Deco style, is how it manages to present Stavisky as a curiosity that, despite preserving the exaggerated qualities of a waxwork, is undeniably human. Resnais and Semprún were interested in Stavisky’s immigrant story and how his fall brought down his adopted country.

Born in present-day Ukraine and coming of age in a xenophobic and anti-Semitic Paris, Stavisky managed to work his way up from small swindles to a crime empire (he even owned the Empire Theatre). Along the way, he won the confidence of the country’s highest officials and orchestrated an international false bonds con that, in 1934, managed to sink the liberal French government, implicating its ministers and the police in the plan.

Stavisky, a macher and an assimilated capitalist, was no court Jew until it became convenient to crucify him as such. Though Resnais takes great care to present Stavisky and his demimonde at some distance.

To begin with, the film marked the first time Resnais cast a movie star, Jean-Paul Belmondo, in a lead role; he wanted Belmondo to be seen as Belmondo playing Stavisky and not as Stavisky himself. Resnais imbued the film with more artifice by choreographing it to an original score by rising Broadway composer Stephen Sondheim. Resnais even insisted on filming only with camera setups that were achievable in the ‘30s, when the film takes place to give it a semi-antiquated feel.

But all these gestures toward distance are for the sake of theater – one of Stavisky’s passions. Pretending, after all served the man well in his confidence tricks and in his act of assimilation as a Jew in a Christian country.

Not content to settle for one version of this narrative, Resnais and Semprún bundled the film with three. “Stavisky” opens with Leon Trotsky receiving asylum in France and ends with his deportation. Along the way, Erna Wolfgang (Silvia Badescu), a German refugee actress and a link between Stavisky’s story and Trotsky’s, appears with her own view of how to present as Jewish to a hostile world.

“Why broadcast that you are Jewish?” Stavisky asks Erna.

“Because I am,” she tells him in the lobby of his theater, standing before a mirror. “Would you like a more theatrical answer? Because when I look at the trees, roses, sky, I know I’m Jewish. I hate races that don’t know themselves. Jews who think they’re happy, have equal rights and are ‘safe.’”

Stavisky, smiling, responds with his father’s advice, “Be average so they forget you.”

Of course, Stavisky is anything but average. He makes a grand impression with an ever-present red rose boutonnière, a beautiful French wife, Arlette (Anny Duperey), and a spendthrift lifestyle that’s all for show. His own identity, and his feelings towards his father are ever-shifting. He is introduced as Serge Alexandre, his intimates call him Sacha, and we learn he went by many names since his small time thievery began at his dad’s dental practice, where he stole gold fillings.

On the anniversary of his father’s suicide, committed after Stavisky was first arrested, he wanders to a graveyard and lies down on a coffin-shaped headstone. He’s soon joined by his physician, Dr. Mézy (Michael Lonsdale), who hovers over him.

“Honor and work, that’s all he ever talked about,” Stavisky says of his father. “Did they honor his name in the Ukraine during the pogroms? But he wanted to forget that. He wanted to be nice, a respected dentist. If grandfather hadn’t laughed he’d have gone to Mass!”

For all his striving, Stavisky can’t escape his father’s idea of willed amnesia. He shouts at his lawyer, who is concerned about an upcoming court date for crimes he committed years ago. “I’ve decided to forget… Why ask me about that poor jerk out on bail? That small time conman. Don’t mention him to me again.”

In the end, Stavisky appears to die like his father too: By his own hand, though the circumstances of his death remain suspect to this day.

“Stavisky” is structured similarly to Semprún’s screenplay for Costa-Gavras’ “Z,” based on the assassination of a Greek politician. In the third act, in the context of a Parliamentary Committee hearing, we receive the background for much of what occurred in Stavisky’s day-to-day life and his jaunts to Biarritz. Slowly, the nature of Stavisky’s crimes and the investigation into them by Inspector Bonny (Claude Rich), are revealed.

But the film is less interested in the specifics of Stavisky’s grift, and more committed to a character study. When Stavisky’s team learns the police are at his apartment, they don’t quibble about the facts of bogus vouchers from Bayonne, they outline their case against him.

“We don’t know you any more,” Borelli (François Périer), Stavisky’s right hand man tells him. “We’ll say we saw you once, in a restaurant… know what else we’ll say? That it’s really not very surprising. You should never trust foreigners… refugees… Jews.” Then the camera spins around Stavisky as he stares ahead, crestfallen, at the floor: A Jew on display.

As for the massive fallout of Stavisky’s crimes — a reckoning that possibly exceeded the consequences of the Dreyfus Affair, which Semprún went on to dramatize in a 1995 TV movie — it is glimpsed only in suggestion.

Seated on a stone wall, Erna Wolfgang watches history unfold as Trotsky, shaving cream still in a lather on his face, is escorted out of his hideout. Beside Erna is her companion, Michel (Jacques Spiesser), who lays out his view of events.

“Just when France must fight against fascism Trotsky won’t be here. The left will splinter without him. And to think that it’s all Stavisky’s fault!”

Without Stavisky, Michel says, the Radical-Socialist government would not have been forced to step down amid right-wing riots on February 6, 1934, when police killed 15 demonstrators. Without that development, liberals might have stayed in power. Instead, Gaston Doumergue, a conservative, became Prime Minister.

History knows what the consequences of this step towards conservatism meant for the country’s future as World War II loomed, even if Stavisky, who died well before it, never would.

PJ Grisar is the Forward’s culture intern. He can be reached at [email protected].

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO