A Love Letter To Max Blecher, Scars And All

Scarred Hearts Image by Big World Pictures

Pott’s disease is a form of tuberculosis that bypasses the lungs and takes up residency in the bones, particularly the vertebrae. It is this macabre ailment that afflicts Emmanuel, the protagonist of Romanian director Radu Jude’s new film “Scarred Hearts,” playing at Manhattan’s Anthology Film Archives starting July 27. By the time the movie begins, the disease has already claimed a vertebra from our hero. “It wasn’t stolen like from a store. It was worn away by microbes,” explains his heavily smoking, avuncular doctor. “Completely eaten. Like a tooth with a cavity.” Alongside Manu, famous sufferers of the disease include Marxist philosopher Antonio Gramsci, Franz Ferdinand assassin and WWI-catalyst Gavrilo Princip, and Romanian-Jewish writer Max Blecher.

It is upon Blecher’s novel of the same name that the film is based, and it begins with images of the writer himself, first a sketched self-portrait (in which the author somewhat resembles singer Klaus Nomi), then a sequence of worn, black-and-white photographs, that generally show the writer in a horizontal position. Born to a bourgeois Romanian-Jewish family, Blecher based his novel on his own experiences with the disease, which didn’t prevent him from enjoying a cosmopolitan and productive, if shortened, life (he died at the age of 28). He contributed to a literary journal edited by André Breton, and corresponded with such luminaries of the interwar intelligentsia as Breton, André Gide, and Martin Heidegger. According to his admirers, he’s a hidden genius of modernist literature, another in a series of lost Kafkas scattered throughout the wreckage of twentieth century Europe. For those unfamiliar with Blecher’s work (including, in the interest of full disclosure, this critic), Jude includes sporadic intertitles showing fragments of his novel, which suggest an imaginative existential wit. An early one reads: “I felt that I was very loosely glued together.”

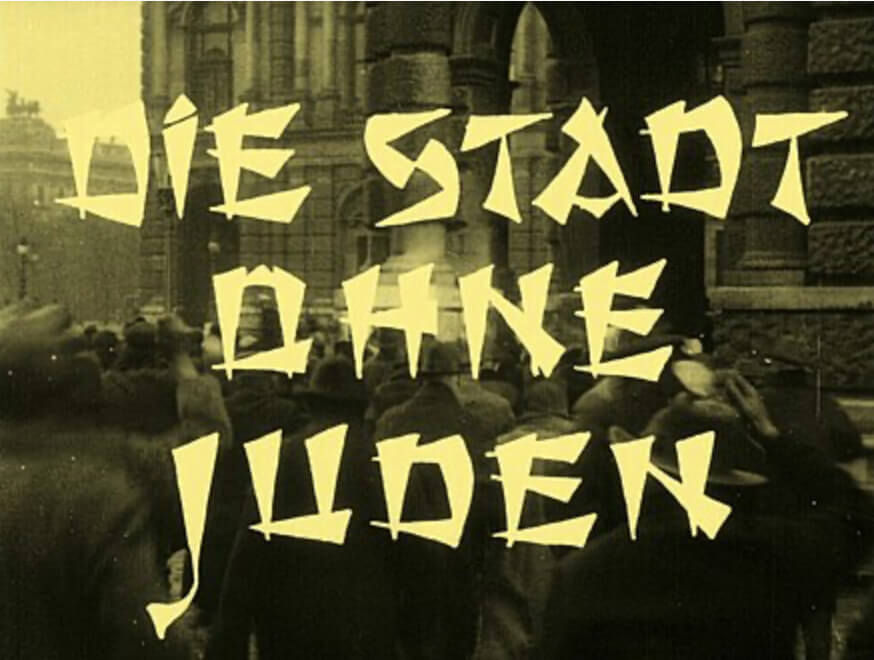

As the list of his correspondences might imply, Blecher’s disease did not keep him from being vitally in touch with the currents of his times. Likewise, Jude’s film never loses sight of its historical context —1930s Europe with its tumult and tidings of doom — and meticulously recreates the time and place. The clinic in which Manu is sequestered, scenically nestled on the coast of the Black Sea, comes to take on a somewhat microcosmic role, displaying in miniature the conflicts brewing on the outside; and indeed this gives the film a poignant if straightforward allegorical sweep: whether by history or disease, that all we see is destined to be swept away.

Integral to the film’s historical inquiries is the role of European anti-Semitism, which is represented in the hype surrounding ascendant fascism but which is by no means limited to it. In one incisive moment Manu tells a lover about an impactful moment from his childhood, when he encountered a group of newspaper boys on the street shouting anti-Semitic slogans. “It’s not so much that three boys can shout, ‘Die, Jews!’” he puzzles. “It’s that their shout can pass unnoticed, unopposed. Like a tram bell.” In an earlier scene, the patients throw a lively party that turns combative as Emmanuel offers his opinions on the issues of the day, starting a vociferous argument with an emboldened anti-Semite. Though contentious, their argument doesn’t faze the partiers – so integral are such debates to the moment’s zeitgeist – and rather than bring a hush to the proceedings, their high stakes conflict blends into the music, joking, and flirting. A fight eventually does break out, but it’s another patient who sets himself on a bedridden man for spreading sexual gossip. Finally another patient, making his sole contribution to the narrative, brings down the house with an impersonation of a certain mustachioed German politician.

It would be misleading, however, to characterize “Scarred Hearts” as either a dark metaphor for the rise of fascism or as an elegy for a lost Europe, a sort of Grand Budapest Sanatorium. The film’s focus remains fixed on Emmanuel, played by fresh-faced newcomer Lucian Teodor Rus, who appears onscreen in virtually every shot. Jude doesn’t shy away from the worst of his suffering – early in the film, Manu must have an abscess popped, a procedure carried out with a cartoonishly robust needle. The camera plants itself about an arm’s reach from his head and remains fixed as our hero lets loose with a series of bloodcurdling screams. Not long thereafter, Manu’s torso is encased in a heavy cast that leaves him flat on his back for the rest of the movie.

As the film progresses, Emmanuel’s physical travails take on a certain metaphysical import. Casting the patients’ active brains against their bodily frailties, “Scarred Hearts” is a work of strict mind-body dualism, and after a point one gets the sense that Manu is imprisoned not only by the sanatorium and his cast, but also by the fact of physical embodiment. As it becomes clearer that his recovery is by no means assured, Manu engages in discussions of the afterlife no less pressing than those centered on current events. Meanwhile, our hero’s peers at the sanatorium cycle in and out through either recovery or death. In the excerpts from Blecher’s writing that Jude sprinkles throughout the film, the word “despair” begins to recur with telling frequency: “futility filled the world like oozing liquid, and the sky, ever fair, absurd and undefined, took on the color of despair;” “all my despair was roaring painfully inside me.”

For all its inquiries into the nature of mortality, however, “Scarred Hearts” is perhaps above all a sort of love letter to Max Blecher, both the writer and the historical personage. Shot in academy ratio by cinematographer Marius Panduru (who also lensed one of the high water marks of the Romanian New Wave, Corneliu Porumboiu’s 2009 comic anti-thriller “Police, Adjective”), the film captures the coastal atmosphere in vivid pastels, the sky above the Black Sea often resplendent in unfamiliar shades of pink and blue. It’s also a humorous film, led in part by Blecher’s onscreen counterpart, a precocious lad with a dorkily theatrical sensibility (one of his favorite categories of joke is to recite advertising slogans as if they were Shakespeare monologues). As must we all, he will shuffle off this mortal coil, but Jude’s film makes for both a fitting and a moving act of memory.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO