Why Claude Lanzmann Still Matters

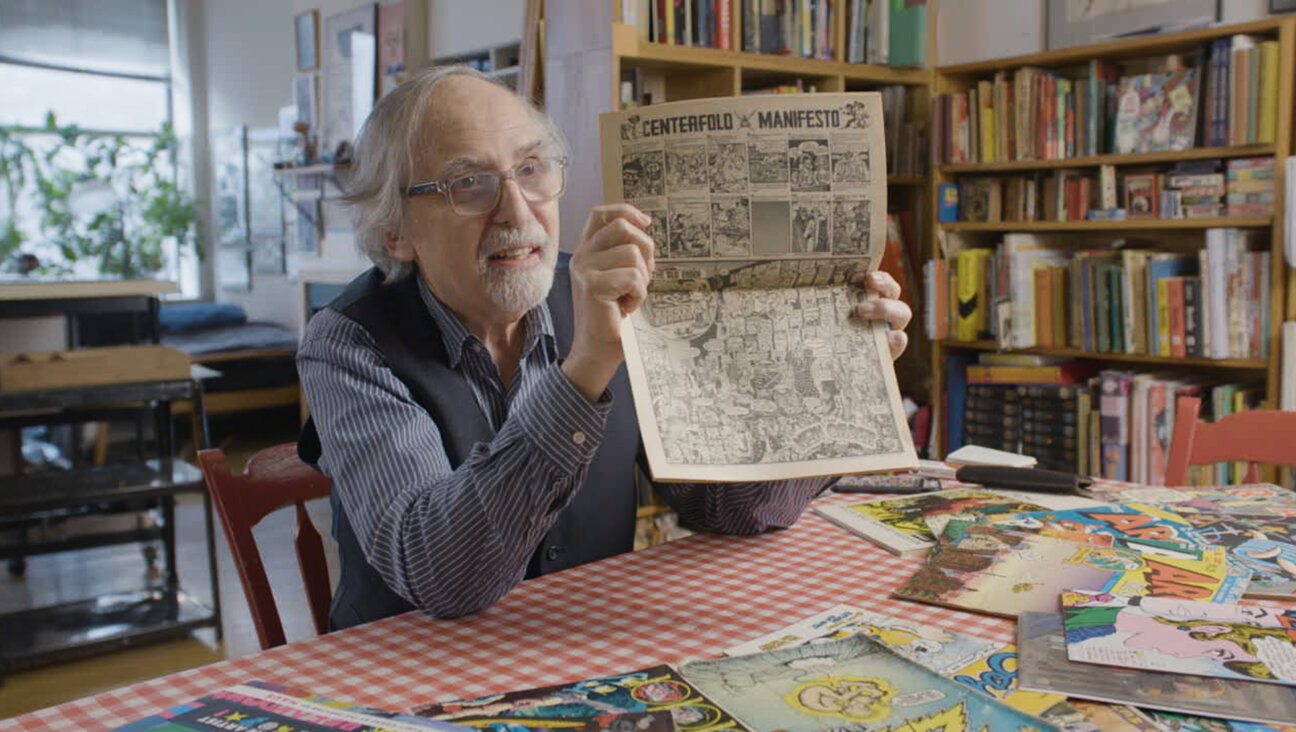

Claude Lanzmann Image by Getty Images

Claude Lanzmann, the French Jewish journalist, author, and filmmaker who died on July 5 at age 92, was not a believer in the proverb “live and let live.” As he explained in his memoir “The Patagonian Hare,” his celebrated film “Shoah” (1985) required aggressively pursuing Nazi murderers to demand explanations of their crimes. Fortunately, Lanzmann reveled in being something of a bullvan, a Yiddish term meaning a brutish person or ox in significant as well as trivial things.

In a memorable column, film critic Roger Ebert described an encounter with Lanzmann at a buffet luncheon at the Cannes Film Festival in 2001. The filmmaker pushed ahead of others who were waiting in line to fill his plate with shrimp. Confronted by Ebert, Lanzmann refused to back down. Ebert adds that a friend recalled how at a New York screening of “Shoah,” he tried to introduce Lanzmann to his mother, a Holocaust survivor: “[Lanzmann] brushed right past her. Didn’t have a moment to spare for her.”

Lanzmann’s focus of attention in “Shoah” was not on individual victims or survivors, but the relentless machine that destroyed most of European Jewry. To depict that machine meant pulverizing filmgoers with 9 and one-half hours of testimony in an endless, elevated reality show. The crushing results were not to all tastes. The American Jewish critic Pauline Kael notoriously did not appreciate “Shoah” as an example of cinematic style. Kael’s bold panning of “Shoah” remains a taboo subject with some readers, to the point where it was conspicuously omitted from a recent collection of her writings from the Library of America.

Born in a Paris suburb to parents of Belarusian and Bessarabian Jewish origin, Lanzmann fought in the Resistance in Occupied France, but claimed to become fully conscious of the persecution of the Jews only after reading Jean-Paul Sartre’s “Anti-Semite and Jew: An Exploration of the Etiology of Hate.” (1946) Primarily a journalist in the swashbuckling tradition of the Russian Jewish reporter Joseph Kessel, Lanzmann became a filmmaker when he was almost 40. The documentary “Israel, Why.” (1973) preceded “Shoah,” which took 12 years to complete. His later films included “Tsahal” (1994), about the Israel Defense Forces, and other documentaries about the Holocaust. This month, “The Four Sisters” premiered on French television. The new documentary shows Holocaust survivors in interviews filmed decades ago.

An habitué of reality, Lanzmann would hurl ferocious critiques at fictionalized versions of the Holocaust, even popular ones. He termed Steven Spielberg’s film “Schindler’s List” “kitschy melodrama.” Nor was Lanzmann generally enthusiastic about Holocaust-themed literary fiction, finding unbelievable the basic premise of a Nazi reminiscing in Jonathan Littell’s “The Kindly Ones” (2006). Lanzmann wrote in Le Nouvel Observateur in September 2006 that he had spent a dozen years trying to get any admission of complicity or wrongdoing from real-life Nazi war criminals while filming “Shoah.” How could Littell’s main character “speak torrentially for 900 pages”? Lanzmann had even more disdain for Yannick Haenel’s prizewinning novel “The Messenger,” (2009) about Jan Karski, a Polish diplomat who tried to inform Allied forces about Hitler’s plans for the Holocaust. In an article from February 2010 in Marianne magazine, Lanzmann grumbled that in Haenel’s novel, an “imaginary Karski is given things to say that he never thought or said, that he couldn’t have thought, in order to falsify the man and history.” At least Littell’s research was accurate, Lanzmann conceded, unlike Haenel’s “feeblemindedness” (faiblesse d’intelligence). As a further response, if one were needed, Lanzmann released a 49-minute film, “The Karski Report,” containing his own filmed interviews with Karski. Paradoxically, Lanzmann had high praise for another French novel about the Holocaust, Laurent Binet’s “HHhH” (2010) for its use of historical sources about how the Nazi leader Reinhard Heydrich was killed in Prague during World War II.

Somehow lost amidst all the brawling, the vehement likes and dislikes, was Lanzmann’s sardonic sense of humor, better expressed in original French texts than in translations. He was no stickler for accuracy about films obviously meant to lampoon Hollywood war movies, so he claimed to relish Quentin Tarantino’s “Inglourious Basterds.” (2009)

Lanzmann would have likely been amused by a memorial tribute from the French Jewish journalist Jean Hatzfeld on France-Info radio. Hatzfeld told listeners that Lanzmann was “very controversial because his personality was a bit rough around the edges… [Lanzmann] was rather egocentric, rather vain, with immense generosity and kindness… Those who are a bit sensitive or easily offended might be put off, but I was amused by him. I never found him unbearable… His egocentricity amused me because I think that if you’ve made a film like ‘Shoah,’ you have the right to be a little pretentious.”

Another laudatory analysis on France-Info was from the historian Annette Wieviorka, who noted that Lanzmann had a talent for getting people to talk, which “historians are not very good at.” This provocative skill in drawing people out, victims and murderers alike, meant that “the word is always at the center of his documentaries, and some have even identified a form of cruelty in that, notably when he questions the famous haircutter Bomba.” Wieviorka was referring to a scene in “Shoah” where Avraham Bomba, a prisoner who had worked as a barber in Treblinka death camp, is pressed by Lanzmann decades later to speak about what he had experienced. On July 1, days before Lanzmann died, Simone Veil, a French lawyer and politician who survived Auschwitz, was ceremonially buried in France’s Panthéon, the resting place of national heroes. A generation of those who valiantly brought the fate of Europe’s Jews to the world’s attention is disappearing.

Benjamin Ivry is a frequent contributor to the Forward.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO