Who Was That Masked Man In ‘Eyes Wide Shut?’

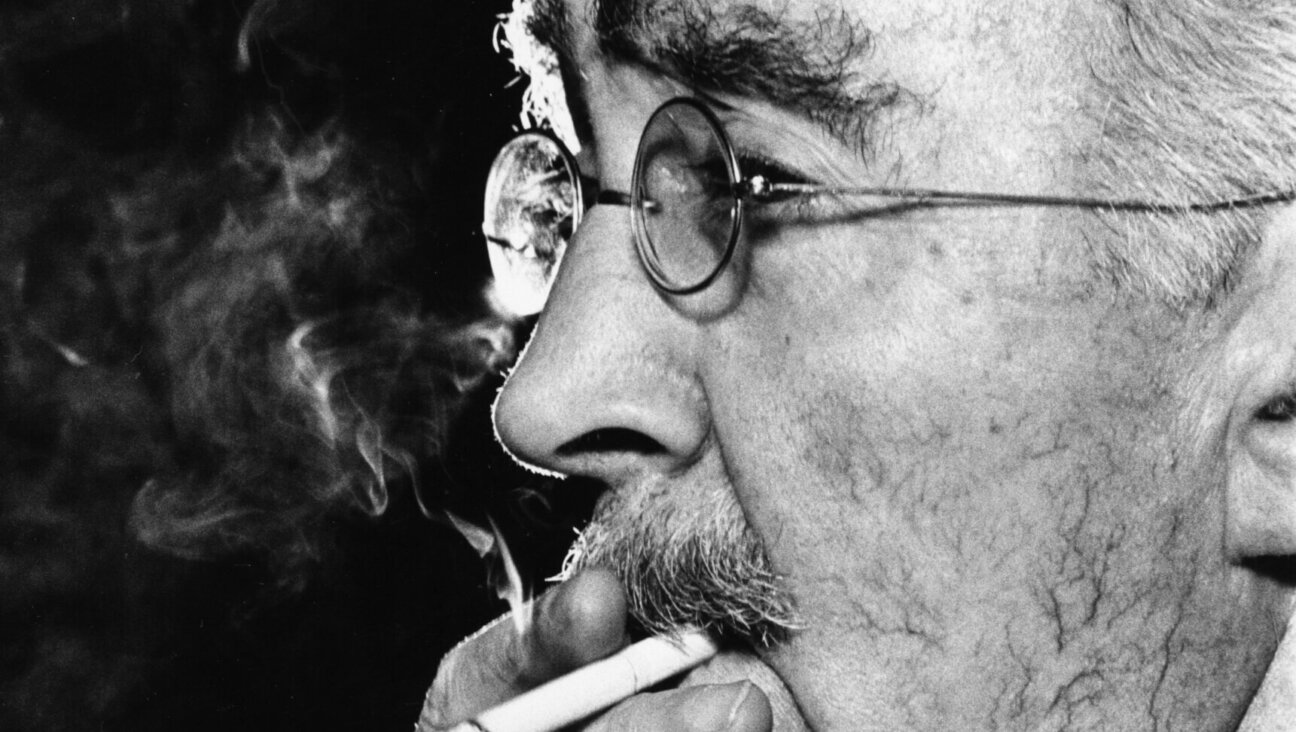

Leon Vitali in Stanley Kubrick’s ‘Eyes Wide Shut.’ Image by Kino Lorber

One of the most iconic moments from Leon Vitali’s career in movies – which began in acting and evolved to encompass an expansive range of activities working as what might with a good degree of understatement be described as an “assistant” for legendary filmmaker Stanley Kubrick — came as he was masked and anonymous.

During a climactic moment in Kubrick’s 1999 film “Eyes Wide Shut,” Vitali appears as a grand authority figure in a highly secretive masked orgy, looming over an interloper played by Tom Cruise. Surrounded by loyal members of his vast conspiracy, Vitali toys with the star who was at that point without question Hollywood’s biggest, threatening him with some unknowable punishment while radiating – even from behind the blankness of his mask – an evocative blend of contempt and relish. For its sheer strangeness and elemental oneiric terror, the scene has been imprinted in pop culture’s collective unconscious, but Vitali’s job didn’t end with the role. “Nothing stopped around this work, it was just an add-on to everything else that I was doing. It was just, this is the task.”

I spoke with Vitali over the phone on the occasion of the release of director Tony Zierra’s new film about his life and career, “Filmworker,” which is the word that Vitali has used to describe his unusual profession. The film opens this Friday at New York’s Metrograph. Although “Filmworker” is likely to be the first that many viewers will have heard of Vitali, he was not exactly an anonymous figure. Before meeting Kubrick, Vitali had a successful career in London as an actor, which led to his appearance in the director’s 1975 period drama “Barry Lyndon.” In it, Vitali plays Lord Bullingdon, the effete, contemptuous stepson who emerges as a foil and antagonist to Ryan O’Neal’s hunky, unrefined Lyndon. While the industry was taken with Vitali’s performance, he was more enamored with the industry, particularly the complex nuts-and-bolts process that goes on behind the camera. When he mentioned this interest to the film’s director, Kubrick told him that if he was serious, he should do something about it and get back to him. Vitali took a role as the lead in a B-movie called “Terror of Frankenstein” on the condition that he be allowed to work as an apprentice in the editing room. Eventually, Kubrick asked him if he wanted to help him cast his next film, “The Shining.”

Vitali’s enthusiasm for the hands-on work of filmmaking remains undiminished by experience. “Below the line people,” he effuses, “they’re the ones who are really in the thick of it constantly. It’s practical in addition to making you use your brains and your savvy. You’ve got to know how to do things and how to keep things together. And if you can’t keep them together, you’ve got to know how to minimize the catastrophe.”

Vitali found in Kubrick a perfect embodiment of what he loved about cinema, experienced as both aesthetic gesamtkunstwerk and existential calling. In “Filmworker,” he describes responding to Kubrick’s directorial credit after “A Clockwork Orange” by saying, aloud, “I want to work for that man.” By the time Vitali met Kubrick, the man’s legend was already well established, a reputation that persists to this day as a sort of poster child for artistically uncompromising studio filmmaking. He had come a long way from his middle class upbringing in a Jewish family in the Bronx, and despite his closeness with the filmmaker, Vitali says that Kubrick rarely discussed his personal life. Still, he says, “I think if you would say one thing about Stanley’s Jewishness, it was that it was entirely secular.”

Nonetheless, Vitali does think that Kubrick’s background played a role in his desire to make a film about the Holocaust, saying, “It was kind of in his DNA, for want of a better word.” The film was to be based on Louis Begley’s semi-autobiographical novel “Wartime Lies” and was given the working title, “The Aryan Papers.” According to Vitali, who worked with the director on pre-production for the film, Kubrick’s approach to the Holocaust was to focus on the subjectivity of a survivor. He describes the angle of the film as “What happened and what do I remember from it?” “When you say ‘Holocaust,’ a lot of people say, ‘Oh yes, I know what the Holocaust is,” Vitali says. “But at the same time, there are nuances inside it, about what the Holocaust was to the people who were inside it, that people don’t think about, that have never been opened up.” Alas, the film was preempted by the release and runaway success of Steven Spielberg’s “Schindler’s List.” Worried about his film’s commercial prospects and emotionally exhausted by the material, Kubrick moved on to other projects.

“The Aryan Papers” was just one of the ambitious director’s multiple famously unmade films (such is the director’s following that Wikipedia devotes an entire page to “Stanley Kubrick’s unrealized projects”). Although Vitali worked with Kubrick for upwards of thirty years, the filmmaker produced only three films during this period: “The Shining” (1980), “Full Metal Jacket” (1987), and “Eyes Wide Shut” (1999). By this point, Kubrick had relocated to Childwickbury Manor, a grand estate in Hertfordshire, England, to the north of London, and gained a reputation of being something of a hermetic figure, though both “Filmworker” and Vitali himself work to complicate this image considerably. “He was such a collaborative person, and not at all the hermit that people describe him as being. He didn’t have to worry about people jumping all over him,” Vitali says. “It wasn’t that he never wanted to go out into the world. Quite the opposite: He went out into the world, but he had something pertinent and something specific that he went out into the world with, which took a lot of time to prepare and maintain.”

Much of the value in “Filmworker” comes in how it adds necessary layering to one’s understanding of Kubrick, an artist who often gets lost behind his own legend. The popular conception of Kubrick paints him as an almost obsessive-compulsive perfectionist, subjecting his crews to an excessive quantity of takes in order to get each detail exactly right. In Vitali’s account, though, Kubrick allowed himself to be guided by curiosity and wasn’t afraid to change things up on the fly. “So Stanley would let the film take him into areas that he might not have thought about,” he says. “That’s what I loved about him, and that’s how he made his films. It continued all the way into the editing process. You were always in a possible state of flux with Stanley.”

Both of these portraits of the director, however, cast him as a relentless worker who demanded the same level of commitment from his collaborators, and “Filmworker” explores the toll that Vitali’s labor took on him as he established himself as the director’s factotum, confidant, emissary, and, occasionally, the object of Kubrick’s formidable wrath. Vitali worked around the clock, handling usually disparate activities ranging from casting and sound work to color timing and even the promotional campaigns for foreign releases of the director’s films. This led him to miss out on family obligations and to undergo towering levels of sleep deprivation. There’s an odd tension in the film between its frank discussions of the specificity of Vitali’s relationship with his employer and its more universalizing impulses, casting Kubrick’s filmworker as an avatar for all of cinema’s forgotten men and women, symbolized visually by a blurred out credits scroll. After all, there’s something a little horrifying about the idea of an industry that asks all of its participants to be Leon Vitali.

And yet the medium is inarguably richer for the tremendous enthusiasm that Vitali, Kubrick, and so many like-minded people have brought to it day in and day out. Even after the maestro’s death in 1999, Vitali has worked hard consulting on new releases of Kubrick’s old films, and he doesn’t seem any less enamored with the process than he was when he first threw himself into it. “We were all there to achieve the same thing, which was to get something down on a strip of 35 celluloid. For me it’s just a miracle that that’s what one did. It’s incredible when you think of all you had to do to get it there, however primitive or however sophisticated… You can’t really call it a job, you’re either in love with it or you’re not.”

Daniel Witkin is a New York-based critic and filmmaker.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO