Why Gad Elmaleh Is the Most Popular Jewish Comic You’ve Never Heard of

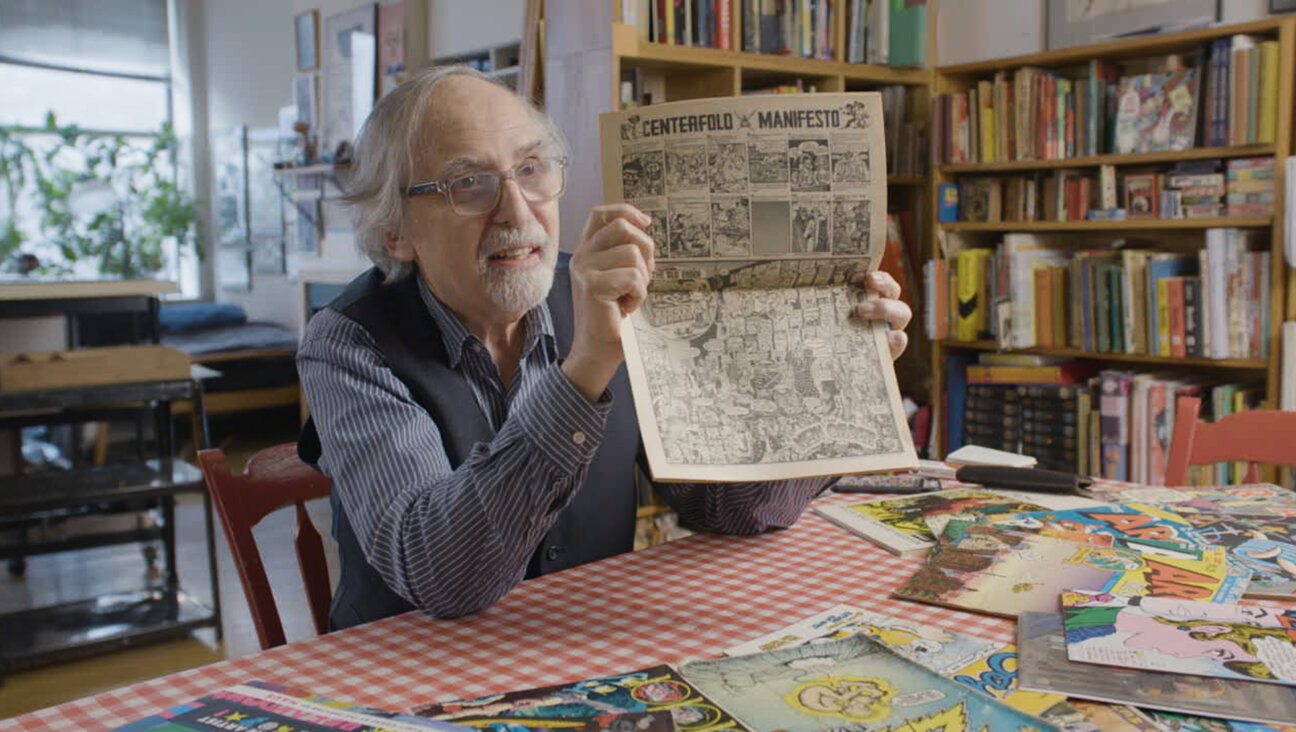

Image by Caroline Lessire

Gad Elmaleh is working out a bit. The Moroccan-Jewish-French comedian and I are sitting in the lobby of a swanky Tribeca hotel the night after his show at Joe’s Pub in downtown Manhattan, talking about his foray into English-language stand-up comedy. Elmaleh, who was born in Casablanca, is wondering whether there’s room in his act to talk about Sephardic Jewish mothers. If he talks about Sephardic mothers to an American audience, he wants to know whether he can expect a certain reaction, a shared cultural assumption.

“When I talk about my mother in France, they know it’s the Sephardic Jewish mother. But the cliché of the Jewish mother for the Ashkenazim is different than for the Sephardim,” said Elmaleh. The comedian is intensely curious; he asks me about as many questions as I ask him. Can the Jewish mother here be compared to the Italian mother? Do Americans have any preconceived notions (preconceived notions are always good for humor) about Moroccan Jews? “Maybe I could talk about the way we sing and dance and do the prayers, so different from the Ashkenazim, or talk about the food, how the Ashkenazim are so … so boring and serious.” Will a bit like this only work in, say, L.A. and New York? Or might it work around the country as well?

You will be forgiven if the name Gad Elmaleh does not ring any bells, though devotees of comedy may have seen him with his friend Jerry Seinfeld on Seinfeld’s web series “Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee,” where the two gadded about the Upper West Side of Manhattan in a 1950 Citroen 2CV, making stops for baguettes, French fries and coffee. Elmaleh is quite possibly the most popular Francophone comedian of the past decade, hosting the César Awards (the French Oscars) three times since 2004 and starring in a string of hit films in France; he also voiced a character in Steven Spielberg’s “The Adventures of Tintin,” played a small role in Woody Allen’s “Midnight in Paris” and had a cameo in Sacha Baron Cohen’s “The Dictator.”

But chances are, if you have heard anything about French stand-up comedy over the past few years, it’s been about the comedian Dieudonné, whose use of an inverted Hitler salute known as the quenelle — inverted because to heil is illegal in France — has come to symbolize the growing prominence of anti-Semitism there. In July 2014, there were wide reports of people making the gesture while protesting the Gaza war; synagogues were attacked, Israeli flags were burned, swastikas were spray-painted and the quenelle seemed to be ever-present. So it may come as a surprise, amid the flurry of news reports about the untenability of being a Jew in France, to learn that Elmaleh, who makes no secret of his heritage and often riffs on Francophone Sephardic culture in his shows, has 4.8 million Twitter followers. He is roughly 36 times more popular on Twitter than Dieudonné who, Elmaleh says with concern and humor, definitely “is the best at being an anti-Semite.”

Now Elmaleh wants to perfect his comedy act in the United States with the goal of eventually building a one-man show: “I want to put some music in it, some impressions, nice set design. I want to mix stand-up and theater, European and American.” He’s been performing at clubs across America for the past three months, and some nights he is accompanied by Harrison Greenbaum, a young comic who nonetheless is a veteran of the business; he does about 700 shows a year, so he’s good for advice on nuts and bolts and can tell Elmaleh if there’s a cultural reason a joke isn’t killing. Elmaleh also has help from Jennifer Dujat, an English language tutor, whom he meets with several times a week.

Elmaleh’s English is superb, but for a comic, being fluent in a tongue isn’t enough. So Dujat comes to the occasional show, lets him know when a case of reversed syntax is dragging down a joke or if he’s mispronouncing a crucial line. She doesn’t work to get rid of his accent — part of what makes Elmaleh’s comedy work here, especially when he plays off stereotypes, is precisely his Frenchness — but they work together to toe that fine line between comic burr and inscrutable utterance.

At Joe’s Pub, Elmaleh was playing to a hometown crowd, full of scarf-wearing Francophones, more well put together than the tired tourists who buy tickets in Times Square and squeeze in next to the Americans on first dates that one sees at dark and claustrophobic comedy clubs. The occasional kippah showed in the blue backlighting before Elmaleh took the stage in a V-necked T-shirt, dark jeans and sportcoat. He’s lean and handsome, and he practices physical comedy with grace that’s not typical of an American performer. Usually, when we think of physical comedy, slapstick isn’t far behind: Consider Ben Stiller or Will Ferrell. But when Elmaleh improvises while doing crowd work and prances around the stage mimicking a French girl frollicking thorugh a field of wheat, you can imagine him looking quite comely in braids and a Breton shirt.

He ranged comfortably across about a dozen topics, from Paris versus New York (in contrast to the old saying about the Big Apple, Elmaleh suggests, for the City of Lights, “If you can make it there, stay there”) to a bit about French tourists searching for Times Square to the jarring politeness of Americans in retail. Why did a young salesman say he’d be “more than happy” to help when Elmaleh asked for a shirt in a different size? Does that mean he’ll be devastated if he can’t find it? Elmaleh has perhaps the funniest bit about taxi drivers around the world that you’ll ever hear.

You get the feeling these are jokes he’s got down pat, and he knows they work well, but the best part of his show is when he opens up about his family. Once he starts to make fun of his mother, the show really takes off. One of the more complex stories of the evening involves his father — an amateur mime, God’s (or Gad’s) honest truth — standing with him on the beach, pointing across the ocean and telling him about the land that lies west of there, a country called America. There’s a joke there that grabs you like a hook in a fish (and yes, he’s got a joke about that too), and this is where Elmaleh is not only a comic but also a showman: He knows how to take the audience on a trip down memory lane, peek ever so slightly at nostalgia, tap wistfulness on the shoulder and then give it a swift kick in the pants.

It’s the rawness of American comedy that Elmaleh enjoys most about performing here. With people sitting just a few feet away — in contrast to playing at a packed arena, as he’s used to — it’s pretty easy to tell whether they want to use their mouths to laugh or finish off their hamburger. After being a star in France, he likes the idea of climbing up the ladder all over again. “I think it’s, to be honest, refreshing, just having something new. It’s like a date. You don’t know what’s going to happen.” It also makes Elmaleh feel the way he did at the beginning of his career, before he was hugely famous. “I’m grateful to the French audience, but I need a break. We’ve sold out arenas, we do tours that are sometimes 12,000 seats,” — “we” here is an indication of the fact that he’s a big enough celebrity to warrant a whole team of managers and assistants and security guards — “we go to Switzerland and Belgium and North Africa and Dubai. So of course when I do a place like Joe’s Pub, it’s refreshing. I go to the venue with my bag, I walk there by myself. I feel exactly what I used to feel. I feel excited.”

Elmaleh was in L.A. when the attack happened at the Bataclan theater in Paris; he is still stunned by it all. He played that theater many times — “I know that stage well,” he said. In his show, he pauses the act for a minute to remember the attacks.

Elmaleh can recall a time, from his childhood, when things weren’t so tense. I want to know whether he freely discusses religion — his own, other people’s — when he performs in France, and he admits that in the past few months, it’s become harder to talk about it. In New York, he says, when he begins a residency at Joe’s Pub that’s running through March, he’s going to start discussing religion more: As a Jew with fond memories of his Casablanca childhood and who’s performed and is beloved all over the world, including in Israel, he has a unique perspective.

And New York, it seems, is the place to take the conversation a step further. He thinks this city is ready for some boundary-pushing comedy, though there’s still a ways to go.

“In America, they don’t realize, they don’t even believe. They say, Where did you live? I say in Morocco. All they have to know is that Morocco has been the only Arab country in the world where the Jews and Muslims lived together in the mellah, the ghetto. When I was a kid, the guys who were working in the synagogue were Muslim. But times have changed, and people don’t want to admit that.” He points out that King Mohammed V defied Vichy France, which controlled Morocco, when it attempted to enact laws against the Jews. “Without Muhammad the Fifth, I wouldn’t be here,” he said laughing, “so thank you Mohammed the Fifth!”

Ross Ufberg previously profiled Kinky Friedman for the Forward.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO