Our greatest Jewish sculptor has a passion for life and a soft spot for Mallomars

With a new exhibit at Pace, 83-year-old Joel Shapiro is still creating and still improvising

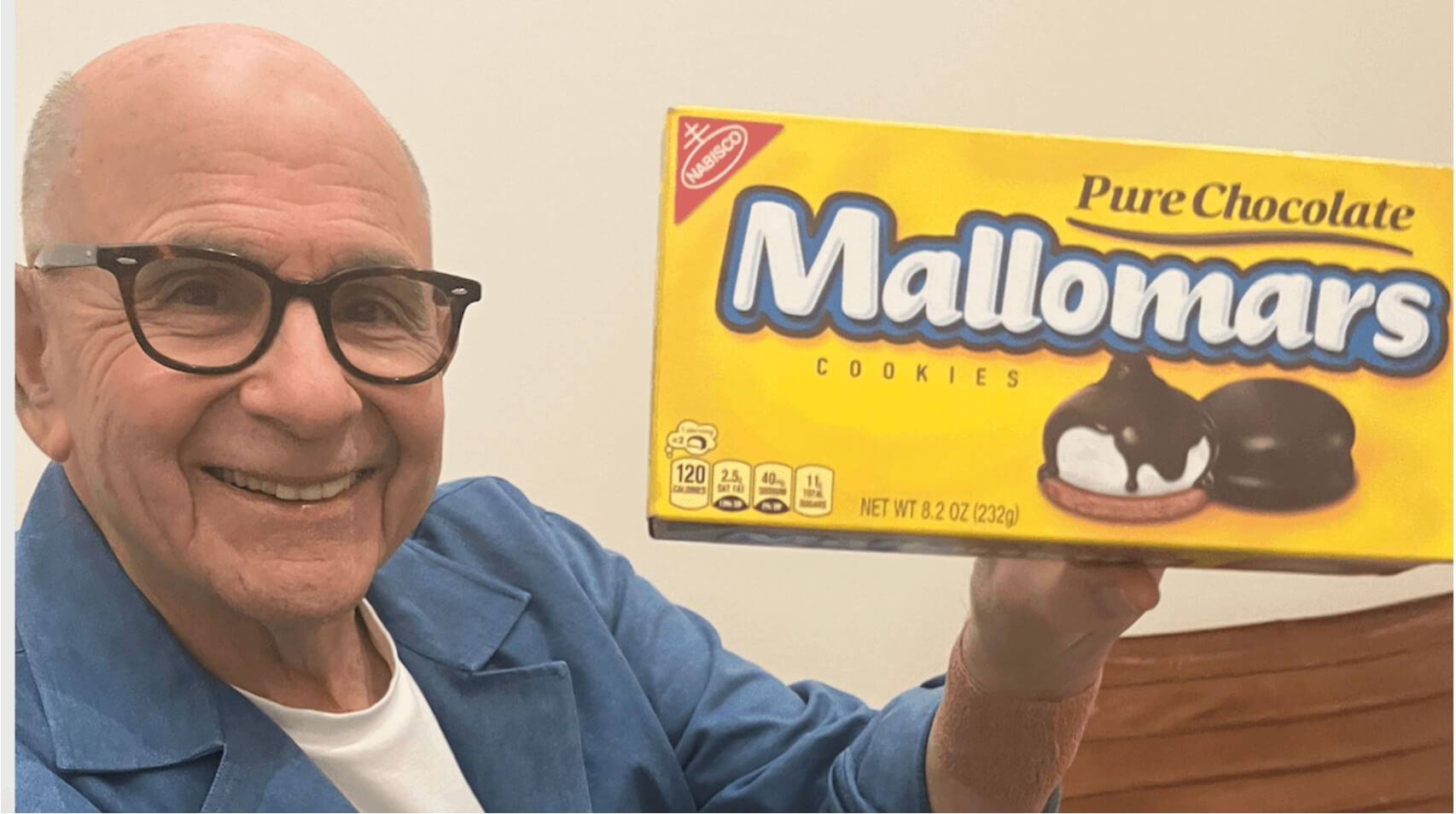

Joel Shapiro and a favorite NYC treat. Photo by Laurie Gwen Shapiro

Joel Shapiro is 83 and one of our greatest living artists. How many people are the greatest living anything? My father, before he passed away at 99 was certainly the greatest living flirter with nurses. It’s not much of a connection until you understand that Joel Shapiro and my father are/were Mallomars fans.

Ok, still tenuous.

But after spending a day with Joel Shapiro at the Pace Gallery when I realized that I am forever in awe of people who defy both age and the gravity of life, I was able to understand the connection my heart made before my brain could articulate it. My father may have grown older, but the world was always new to him. And that’s exactly how Joel Shapiro seemed to me.

After a few pleasantries, Shapiro said he would walk through his new exhibit with me. Slender and wiry, he moved with a kind of quiet precision. His outfit — a blue chambray jacket, white tee, khakis, and New Balance sneakers — was casual, yet carried the unmistakable vibe of someone who has spent decades making art. I had seen photos of him in his youth, and though his hair was now closely cropped and thinning, he still carried that same handsome, thoughtful presence.

It was two days before the opening of Out of the Blue, his first solo show at Pace in a decade, and we were standing in front of the showpiece, his massive, nearly 12-foot-tall sculpture. ARK — if you see it in person you’ll understand why the title is all-caps. “Let’s do something we shouldn’t,” Shapiro told me. “Touch the work.” The security guard didn’t move a muscle, and I got the thrill of doing something that would normally get me thrown out of a museum.

“It’s the biggest wood construction I’ve ever made, but I think it’s not monumental, it’s within human experience. Wood is natural, you see the wood grain even through the paint.” He had me touch ARK again. “The ends are spruce, and this is aircraft-grade plywood.” He pointed out hollow, solid, and composite parts of his work. “These are very light, highly technical structures that I think retain intimacy. I think paint really helps.”

Lots of artists today sketch a miniature version of a work then use a computer to envision it on a grand scale. “Do you use any imaging programming now too?” I asked.

Shapiro shook his head. “No. I just work by hand.” He beckoned with a finger and led me to the smaller exhibition room filled with studies for larger works. He stopped at a colorful maquette — a small-scale model used to experiment with ideas before creating full-size sculptures. “I pull a bunch of wood scraps together, without any sense of how I could ever make it larger,” he said, using his hands to mimic how quickly he pins pieces together. Then he showed me a more refined version held together with screws. “Once I like it, I go big, with help from my assistants.”

Kind of blue

At the gallery’s center, ARK seemed to twist and stretch, its colorful limbs reaching outward as if caught in a storm. Next, we stopped at Wave, a vibrant green, blue, and black 8-foot piece. “I like this one too,” Shapiro said. “There’s a maritime theme going on here.” To my mind, it captured an abstracted sense of the ocean’s restless energy, with the colors and forms playing off one another in lively contrast. Then we arrived at Splay, its bold blue and yellow planes jutting upward, frozen mid-motion. Each piece challenged the viewer’s sense of balance and space, pushing boundaries while still grounded in the physicality of the materials — their weight, texture and form.

As Holden Caulfield might say, the blue in his work just knocked me out. Shapiro beamed. “It’s an intense blue,” he said. “A combination of two blue colors. I mix the color myself with an assistant, with powdered pigment and casein solution. Getting the blend right is like cooking.”

Some members of the Pace staff call his signature shade “Shapiro Blue,” and there’s even a curious claim on Wikipedia linking it to Judaism. Shapiro chuckled. “I don’t know about that. People love talking about Yves Klein Blue. This is just blue — like the ocean, the sky. It’s not mine, but it’s definitely sublime.” He pointed to a section of vibrant orangey red, adding, “The Japanese call this color Shōjōhi. I was really anxious about the colors with this one. The form is so radical, and the safer option would’ve been to focus on it and stick to one color.”

For most of his career, Shapiro has not named his pieces. When I asked why he did this time, he smirked, “I’m growing up! Assuming greater responsibility for my work.” Then, with more seriousness, he added that naming them gave a narrative layer. “It helps people see beyond the abstract forms. What really fascinates me is how the ground and flatness determine form. I’ve always been struggling to get away from architecture. My work strives to be antithetical to space — it’s not dictated or shaped by it. That tension excites me. I think I succeeded here. This is a great show. This is a lively show.”

Of Mallomars and almond cookies

In a private gallery office, an assistant brought us each a coffee and set them down on a glass table near a maquette of some nascent creation. I clutched my cup. “I really don’t want to spill coffee on a Joel Shapiro,” I said.

The assistant whisked the maquette away as Shapiro watched with an amused look. “Casein is pretty water-resistant once it dries,” he said. By now, we’d hit it off, but just in case we hadn’t, I had an ace up my sleeve. Why waste it?

“Before I start, I have to tell you I brought you a tiny gift to start the fall and celebrate your new show.”

Shapiro’s eyes lit up at the sight of the familiar yellow box. “Mallomars? Wow, I haven’t had one in ages.” I grinned, thinking of my dad, who could never resist a Mallomar. At 99, he still managed to polish off a box like it was his duty.“They’re only available in the cooler months,” I said as he eagerly opened the package. “Today’s the first day of the Mallomar season!”

“I love them,” he said, “But my favorite cookie was those almond cookies from Chinese restaurants. I was always in Chinatown as a kid — my grandfather had a leather goods company on Gold Street. My cousins and I would hang out, drive him crazy, then we’d all head to Joy Garden for a meal. That was my Chinese restaurant of youth. Later, I was taking a seminar with Irving Sandler, the art historian, and he introduced me to a place called Canton, and that became the standard restaurant. Eileen Leang ran it, and her husband Larry was the chef. Well-known artists, as well as architects like I.M. Pei, were regulars. One day, Eileen just vanished. Years later, I ran into her at Russ & Daughters. She walked in by chance. I said, ‘What happened? Where did you go?!’ She said the pressure was too much.”

The unbearable lightness of Schnabel

Just as I was about to share my family’s love for the crispy duck, and eggplant stuffed with pike mousse at Canton, Shapiro’s cell went off — the unmistakable, loud ringtone my hard-of-hearing dad had once chosen. He glanced at it. “I better take this,” he said.

“You’re here? I’m in the middle of an interview,” he said, raising an eyebrow at me. Then, he grinned. “You want to meet Julian Schnabel?” he asked.

(Yes.)

We walked back into the exhibit rooms where 72-year-old Julian Schnabel — the renowned painter and filmmaker, celebrated for his bold, expressive works and larger-than-life personality — was sporting an all-white jumpsuit. A towering presence in the art world since the 1980s, Schnabel made his mark with oversized plate paintings and later ventured into film. He made a beeline for a small untitled bronze sculpture Shapiro had pointed out earlier in the smaller room.

“Joel! This small one’s a masterpiece! I need something like this — giant — for Montauk!”

(Shapiro didn’t say no.)

Schnabel turned to a little girl, maybe four. “This guy — my buddy Joel — made all these sculptures! What do you think?”

His granddaughter smiled shyly.

“Kids are the purest critics,” Shapiro said, taken with the moment.

“I didn’t even know Joel was here when I saw these,” Schnabel said to me. “I called him right away and said, ‘Heartbreakingly beautiful.’”

“When did you two meet?”

“I came to New York in ‘73,” Schnabel said. “Lived in Joel’s studio — ”

“I had a loft on Leonard Street,” Shapiro interjected. “Rent was $120. Julian needed a place and wouldn’t stop bugging me. I finally told him, ‘Paint the ceiling, and I’ll let you stay for free.’ He wasn’t famous yet, but you could tell he had something special.”

I now found myself part of Julian Schnabel’s entourage (which included members of his family and Myra Babenco, the stunning film producer daughter of Argentine director Héctor Babenco) as he led us two-by-two to ARK. I walked alongside a junior gallery curator, eavesdropping with clear fascination as Schnabel spoke. “Joel’s got clarity — wood, color — taking simple elements and doing something new, that’s the enchantment,” he said. “It’s like The Unbearable Lightness of Being — light, beyond language. We’re all just passing through, right?”

“Do you both think there’s something to the idea of Alterstil — you know, that late-life style or phase in an artist’s work?” I asked.

Did either of them know the term an art historian had fed me pre-interview? Apparently not.

“Art historians often mention Michelangelo, Rembrandt, and Cézanne as examples of artists creating some of their best work in their later years,” I added, trying to connect the dots.

Shapiro exchanged a knowing look with his friend. “Well, it’s not like we have much choice.”

Schnabel’s eyes shifted to ARK as he spoke. “On 9/11, I assembled a Venetian chandelier while the world fell apart. Now? Gaza, Ukraine, the election — it’s all unbearable. But work like this?” He gestured to the sculpture. “It’s a counterbalance.”

Joel Shapiro: Man about town

When Schnabel left, we returned to the office, and Shapiro grabbed another Mallomar. “Where were we before Schnabel?”

“Chinese food? But maybe let’s start with your earliest memories.”

“That would be in Weatherford, Texas, where my dad was Chief of Medical Services at Camp Wolters during WWII. It was one of the largest infantry training camps of the war, and he treated German POWs.” (Camp Wolters is about 50 miles west of Fort Worth.)

“I read in a 1980s interview that you played war games with other kids there.”

“Well, I remember playing with fire in New York. If I was born in ’41, and we moved back to New York in ’45, this must’ve been around 1946. I grew up on an army base. We played ‘Burn the House of Hitler.’ Kids were always blending war games with fantasies. I loved Buck Rogers too. We moved back in 1945. I was a doctor’s kid. My dad, an internist, wanted me to follow in his footsteps. He’d lost his mom to the 1918 Spanish flu, and his dad was a coffee merchant.”

Joseph Shapiro, his son told me, was a smart, cultured man but had a sharp temper and deep anxiety about money. “He went to NYU, though I think he started at City College. He was a great student — unlike his son.”

“And your mother, Anna?” I asked.

“Ebullient! An immunologist with a sense of adventure. At some point, she made figurative sculptures too, and they were pretty good. I remember going to the Met with my parents and sister, talking about the armor and the Egyptian wing. I didn’t look much at the paintings — they felt too flat. But I loved the sculptures, how they interacted with the space, engaging in a more physical, kinesthetic way. We also went to the Museum of Natural History quite a bit.”

“Did you go through a dinosaur phase like most kids?”

“A big one!” he laughed.

Shapiro freely admitted that while not as wealthy as some, he had a cushy existence. After the war, his family moved to Sunnyside, Queens, a planned community with more than 1,200 apartments, gardens, and the city’s largest private park. Known then as a left-wing enclave, it attracted creatives like actress Judy Holliday and artist Raphael Soyer. “There were a lot of artists teaching classes. I took some clay classes — it all turned me on — but my father discouraged me from pursuing art because he worried I’d starve. As I said, that generation had deep anxiety about money.”

I found a 1959 senior photo of him from Bayside High where he was voted “Man about Town.” He looks every bit the part — fresh-faced, clean-cut, with dark hair neatly combed, giving off serious ‘50s charm, yet wearing a brooding expression.

“Man about town? What’s that about?” I asked him.

He laughed out loud. “That I was social. I did have a girlfriend.”

In the late 1950s, a teenage Joel Shapiro, frequently accompanied by his sister Joan, who was two years older, and more daring friends, would hang out at the Five Spot Café at 5 Cooper Square near the Bowery. On a poetry and jazz night, you might find Jack Kerouac or Amiri Baraka reading their work, followed by Coltrane, Monk, Dolphy, or Mingus playing sets. Shapiro was even there when saxophonist Ornette Coleman unleashed his groundbreaking performances. “Ornette was really challenging.”

“Still listen to jazz now?” I asked.

“Yeah,” he sighed, “not enough, though.”

Does jazz mirror how Shapiro approaches his sculptures?

“As an artist,” he said, “you won’t invent a completely new form — there’s nothing new under the sun. But a combination of things can be new and radical.” (I took that as a yes.)

‘I was scared to death’

When Shapiro entered NYU as an undergraduate, he was still dutifully planning to become a doctor, but he was already working on his art. After completing his bachelor’s, he spent two years in Hyderabad in southern India with the Peace Corps.

During his time in India, Shapiro worked at Gandhian schools and built smokeless stoves to reduce health risks like glaucoma — a practical, hands-on approach that later influenced his sculpture. “I chose India because of my Indian brother-in-law. I taught skills for self-sufficiency — textiles, spinning, vegetable gardening; I planted tomatoes and okra. I had multiple school assignments, and during breaks, I took the opportunity to travel to places like the Ajanta Caves. It felt magical. The experience was transformative, and when I returned, I was torn — how could I please my father while pursuing what I truly loved? The only A I’d ever earned in school was in a painting class. So, I put together a portfolio, showed it to an NYU professor, and they accepted me into the MFA art program — without a BFA.”

“You’ve said over the years you were influenced early on by Robert Morris, Richard Serra, Carl Andre and Donald Judd. Is that accurate? Is there anyone else you’d add?”

“Donatello and Bernini,” Shapiro said, after a think. “But for modern artists, yes. Robert Morris, definitely. There was a 1964 exhibition of his at the Green Gallery that in the early ’60s was really far out — suspended geometric projections, mind-blowing for its time.”

Back then, he worked for the Jewish Museum for $3.75 an hour, helping to install exhibits, polishing silver, and doing other menial jobs. “It was not bad pay for the time!”

“I want to ask you about Anti-Illusion: Procedures/Materials exhibition at the Whitney in 1969,” I said. (Curated by Marcia Tucker and James Monte, it featured Shapiro’s first public work alongside artists like Eva Hesse, Richard Serra, and Richard Tuttle, the latter of whom is also still alive and exhibiting today.) “It was a major group show. Did you feel like you had made it when you were included?”

“No! I was scared to death. I was experimenting with big schemes of colorful dyed nylon, hanging and stapling them to the walls. You can do things in your studio that are intimate and personal, but extending them out, developing them in public, is not an easy feat. Malcolm Morley (the pioneer superrealist) once said, ‘If you can’t develop in public, you can’t grow.’ Showing your work is part of the process of evolving.”

After the Whitney show, Shapiro became more involved with the museum and began experimenting with different materials like clay. His breakthrough came with a show at Paula Cooper Gallery in 1974, where he exhibited small cast works, including a chair, a house, and a horse. He described this exhibition as radical and considered it his first truly significant body of work.

‘Working keeps me going’

When I asked about his family, Shapiro mentioned his two grandchildren: Walker, a senior at St. Ann’s with an interest in film, and Lily, a nearly 20-year-old painter studying at RISD. His only child, Ivy Shapiro, from his first marriage to Amy Snider, is also involved in the art world as an advisor. (As we were discussing family, Ivy stopped by Pace to say hello — and shared a Mallomar with her dad.)

“Did having kids change your approach to your art?” I asked after Ivy left the room to take in the show before it opened. “Make you more cautious?”

“If anything, it was harder on them,” he said. “New York art kids didn’t grow up in the suburbs. Ivy used to visit me after my divorce from Amy, and I’d set up a pop-up tent for her in my gritty Tribeca loft. Artists would bring their kids to gallery openings — it wasn’t the typical childhood. Was it great for them? Maybe.”

“Any more thoughts on that divorce?”

“Traumatic for all of us, but I was happier after. I remarried the artist Ellen Phelan. We’re still married.”

As we spoke about his life and how it’s evolved, I wondered how he had managed the ups and downs over the years — something many artists struggle with. “Have you battled any addictions?” I asked.

He paused. To be fair, that question came out of the blue. “I used to smoke, but I quit. I’m doing fine now — well, for the most part. I see a physical therapist once a week.” Shapiro gave a classic shrug, a mix of resignation and humor. “Who really wants to live to 100? My mother made it to 99. She’d sit in her apartment at 2 Fifth Avenue and say, ‘I’m the last one left — now what?’”

That answer hit me squarely. My father, Julius Shapiro, who also lived to 99 before passing away from old age in 2020, faced the same question, though his response was to keep reading and charming every nurse who crossed his path. Both he and Joel Shapiro’s mother shared that uneasy feeling of outliving their peers. And while there’s no relation between us that we know of, Joel isn’t content with reflecting on past glories. He’s still chasing the thrill of creation, building something new each day, as if the vitality that once bound him to youth has only grown stronger with time.

As our conversation wound down, I couldn’t resist asking: With his legacy already secure in the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, the Guggenheim, MoMA, the Whitney, and major museums worldwide, why keep pushing so hard?

“I’m still improving,” he said. “Working keeps me going. As long as I don’t get Alzheimer’s, I’ve got plenty of work left in me. The joining together, the arranging, the language of sculpture, how it transcends cultures. All that still thrills me every day. What I am still aiming for is work you cannot refute.”

“Out of the Blue” runs until Oct. 26 at Pace, 510 W. 25th Street, NYC.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO