In concentration camps, Jewish artists painted in secret, hid their work and traded art for food

Website launched for Yom Hashoah shows art made by Jews in Nazi camps and ghettos during World War II

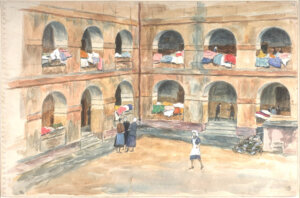

A painting of the Kovno ghetto in Lithuania, 1942, by Esther Lurie. Courtesy of ORT/Art and the Holocaust

They drew in secret, trading art for scraps of food and hiding paintings in jars and walls. But ultimately these Jewish artists working in concentration camps and ghettos during World War II created a record of their daily lives as Nazi prisoners. Their sketches and paintings documented the horrors they witnessed as well as their hopes and fantasies.

Now work by 30 of these artists can be seen on a website, Art and the Holocaust, launched Monday to mark Yom Hashoah, the Holocaust remembrance day. The site was developed by ORT, the Jewish educational organization, in collaboration with Israel’s Ghetto Fighters House Museum.

In some cases, the artists were ordered by the Nazis to copy famous paintings or do technical drawings, and they did their own work in secret. In other cases, camp administrators encouraged artists to create paintings and drawings in order to perpetuate falsely benign views of camp life.

Images of beauty despite the horrors

Charlotte Buresova, imprisoned in Terezin, was assigned to copy work by Rubens and Rembrandt for the Nazis. But for herself, she drew children, dancers, musicians and flowers — images of beauty in contrast to the horrors around her. She escaped from the camp shortly before liberation. Another Terezin inmate, Malva Schaleck, hid her paintings in camp walls. Schaleck was sent to her death in Auschwitz. Her art was discovered after the camp was liberated.

In Lithuania’s Kovno ghetto, the Judenrat — Jewish councils set up by the Nazis to implement their rules — asked Esther Lurie to document ghetto life. She hid 200 drawings and watercolors in jars, 11 of which were recovered after the Nazis liquidated the ghetto and burned it to the ground.

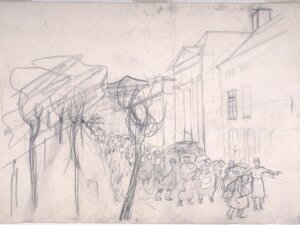

Lurie’s painting Ninth Fort, showing a figure surrounded by fencing and heading uphill amid a bleak brown landscape, depicts what she called “the ‘road of torture’ along which thousands of Jews passed,” as they left Kovno en route to death camps. She herself was sent to the Stutthof camp, where she managed to find a pencil and paper scraps to do portraits for other prisoners in exchange for food.

“Young girls, who had ‘friends’ among the male inmates and who used to get gifts of food, asked me to draw their portrait,” Lurie later wrote. “The payment — a piece of bread.”

Lurie was ultimately sent to a work camp in Germany, liberated by the Red Army in 1945, and moved to Palestine. Her work from the war years was exhibited as official documentary evidence during the 1961 trial of Nazi official Adolf Eichmann.

Punished for art made in secret

Some camps were permitted to receive art supplies from Jewish and Christian welfare organizations, and in some places Nazi officials even allowed exhibitions to create a pretense of normalcy. In other cases, inmates made art secretly and at their peril. Leo Haas and Karel Fleischmann, inmates of Theresienstadt, were tortured and deported to Auschwitz after a Nazi search of their quarters uncovered work they planned to give to visiting Red Cross representatives.

Some artwork depicted the degradation and terror of camp life — barbed-wire fences, watchtowers, deportations, inmates scavenging garbage for food or using the toilet in public. Others portrayed beautiful landscapes beyond the camps. In “Mount Canigou in the Snow,” Karl Schwesig, who was imprisoned for four years, showed mountains against a blue sky beyond the fence posts of the St. Cyprien camp in southern France.

An urge to create: ‘I was floating’

Aizik-Adolphe Fèder, who painted fellow inmates at the Drancy camp in France, often enhanced his subjects’ appearance to make them look healthier than they were. Feder was eventually sent to his death at Auschwitz.

Amalie Seckbach sketched surrealistic images of flowers and dream-like portraits during her time in Terezin, where she died in 1944. Just eight years earlier, her work had been shown alongside Paul Klee’s at the Art Institute of Chicago.

Halina Olomucki, who survived the Warsaw ghetto and Auschwitz, and was ultimately liberated by the Nazis, painted on demand for her overseers and on request for fellow prisoners. Many of her works portray ghostly figures.

“I never rationally thought that I was going to die, but there was an unbelievable urge to create,” she is quoted as saying. “I was in the same position as all the people around me, and I realized that they were close to death. But I never thought of myself like that. I was floating. I was outside the reality of existence. My task was simply to portray what was happening.”

Work by 30 Jewish artists imprisoned in ghettos and concentration camps can be seen on the website Art and the Holocaust, developed by ORT and the Ghetto Fighters House Museum. A separate online exhibition marking Yom Hashoah launched by the U.S.-based organization Artists Against Antisemitism includes nearly 100 contemporary creative works celebrating Jewish resiliency, including a poem by Dr. Ruth Westheimer.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO