What Houdini, Coney Island and space aliens have to do with the book of Exodus

Joel Silverstein’s ‘Brighton Beach Bible’ blends autobiography, comics and high art with the Passover story

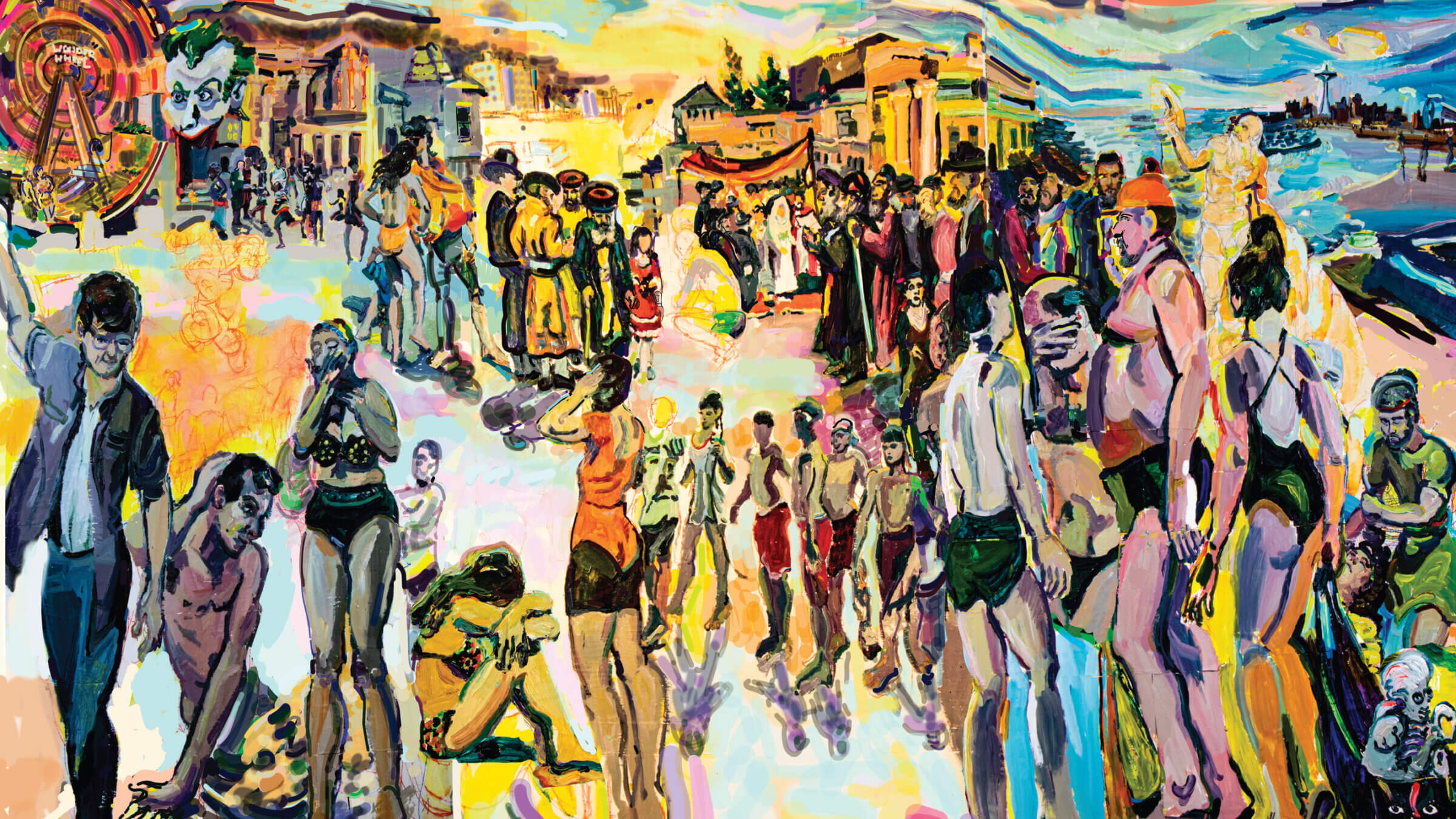

“Brighton Exodus” from Joel Silverstein’s Brighton Beach Bible. Image by Joel Silverstein

Every year at Passover we are commanded to imagine ourselves leaving Egypt — Joel Silverstein painted himself into the picture.

“That part of ‘You were there’ always got me,” said Silverstein, artist and a founding member of the Jewish Art Salon. “I took that as an aesthetic.”

In The Brighton Beach Bible, an art book with narrative commentary, Silverstein envisions the boardwalks and abandoned attractions of his childhood in Gravesend, Brooklyn, in the ‘60s and ‘70s as the staging ground for the Exodus and 40 years in the wilderness. Each painting is introduced with a citation from the Torah. The opening chapter of Exodus relates Moses’ genealogy; Silverstein illustrates the passage with an image of his immigrant grandfather, who arrived in the United States as a draft dodger from the Russo-Japanese War.

A grand, Tintoretto-esque tableaux of the Israelites preparing to leave bondage has them dressed in swim trunks, their poses reminiscent of a Diane Arbus photograph, the Wonder Wheel behind them. Looking closer we see men in shtreimels standing by a chuppah on the sand: a reference to God marrying Israel at Sinai.

Silverstein’s book, which draws its visual cues from Chaim Soutine, b-movies and National Geographic photography is a kind of dizzying pentimento and work of collage. When the artist was awarded a grant to pursue it, he enlisted Georgetown professor Ori Soltes, director and chief curator of the B’nai B’rith Klutznick National Jewish Museum in New York, to write accompanying text, which delves deeper into Silverstein’s influences and references.

“I saw all kinds of things going on in the work that ranged from comic books to Michelangelo and everything in between,” Soltes said.

Brighton Beach Bible is a work of visual midrash that, at its busiest, functions like a Bosch painting or a Where’s Waldo page. Even the less crowded images, like that of Moses beholding the burning bush, are strewn with allusions. The younger Moses braces for revelation, an image of his older self, as carved by Michelangelo, on his shirt. The “Angel of the Lord” present at the event is a sci-fi alien. The bush, Soltes’ commentary points out, resembles the Torah niche in the Dura Europos Synagogue in Syria, widely held as ground zero for Jewish representational art.

When the Israelites cross the Red Sea, who is there in the foreground but the Jewish master of escape, Harry Houdini, standing ready to free himself from his chains.

For Silverstein the series, drawn from a body of work going back 20 years, is a way to celebrate his background in a field where he believes Jewish artists to subsume their roots in favor of marketable universality. It is also a way to square the Jewish people’s collective history with a personal one.

“It became more and more kind of a legendary mythic place,” Silverstein said of Brighton Beach, which he left in his own Exodus to New Jersey in the 1980s. “It was both my Egypt and my Israel.”

Correction: This article originally referred to Silverstein as the co-founder of the Jewish Art Salon. He is a founding member and, with Richard McBee, director of exhibitions for the Jewish Art Salon.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO