Influenced by comic books, Salvador Dali and Mark Rothko, a Russian-born Jewish artist embraces his contradictions

Yury Kharchenko uses his art to address antisemitism, the Holocaust and Oct. 7

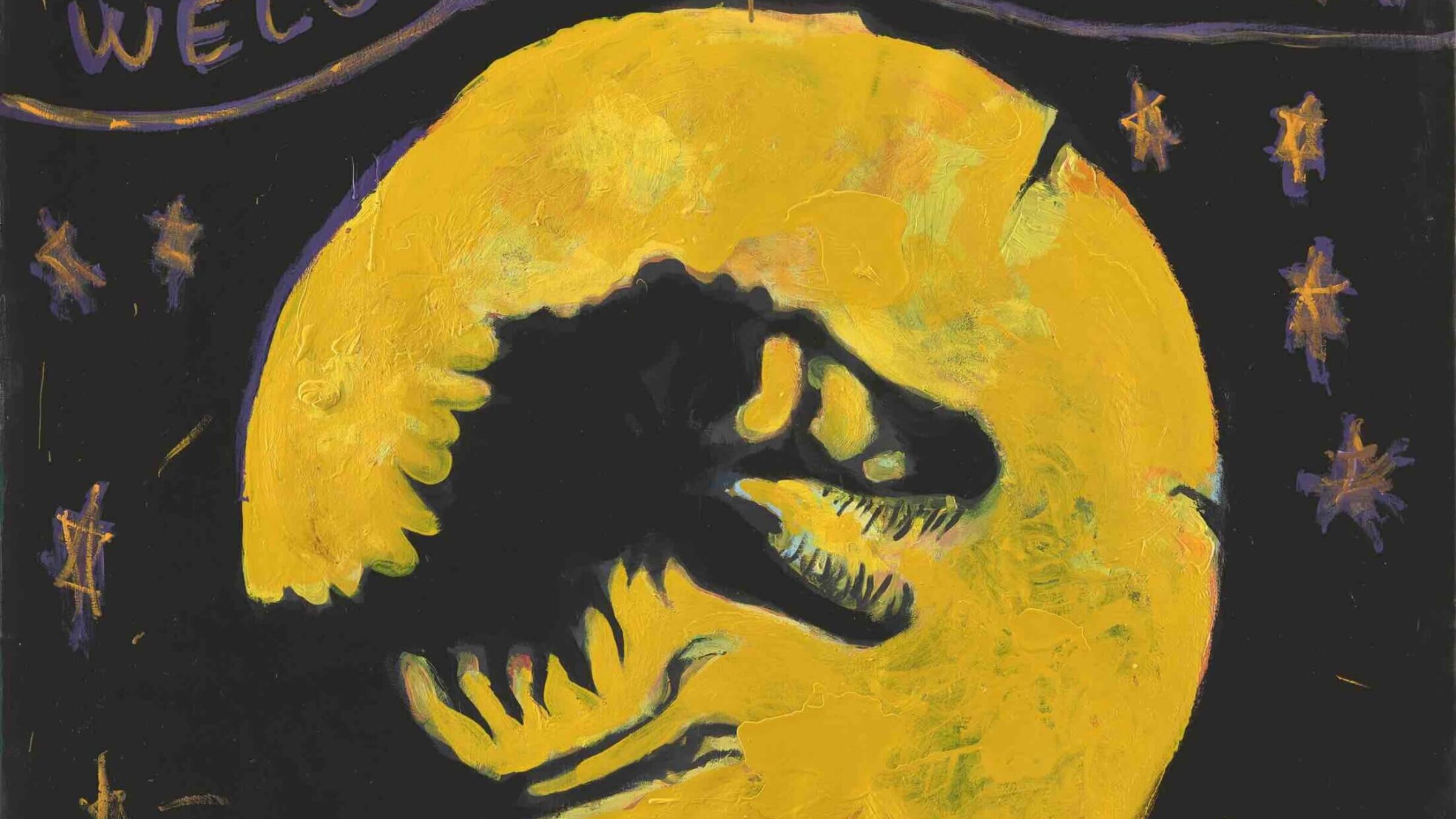

Yury Kharchenko’s ‘Welcome to the Jewish Museum’ Image by Yury Kharchenko

Born in Moscow and raised in Germany, Yury Kharchenko, a descendant of Holocaust survivors, often uses painting to express his complicated identity as a contemporary Jew. His work merges pop-culture references (Jurassic Park or Marvel comic strip characters) with fantasies of violence and taboo allusions to Shoah. In one painting, a T-Rex is posed in front of the Auschwitz entrance gates where the sign reads, “Welcome to the Jewish Museum.”

“I wanted to point out the question of how remembrance cultures become mere show business,” Kharchenko said, referencing a discussion between Spielberg and Claude Lanzman, the director of the documentary Shoah.

In his work, Kharchenko explores such themes as the paradox of normality and barbarity occurring simultaneously; the commercialization of the Holocaust; and, in the process, the eradication of its memory, which, for Kharchenko, is the true abomination.

His images, he says, also hint at the current wars in Ukraine and Israel, though he adds that the monstrous specificity of the Holocaust makes it a universal symbol of darkness that cannot be compared to anything else.

Kharchenko, 37, spoke to me from his home in Berlin on the occasion of the publication of his newest book, Yury Kharchenko: Paintings (2018-2023).

Kharchenko attended the Düsseldorf Art Academy, and in the wake of antisemitic assaults he personally experienced, he devoted himself to the study of Torah, Talmud, Jewish ethics and philosophy at Lauder Yeshurun Yeshiva, a Berlin-based Orthodox Jewish school founded by Ronald S. Lauder. Later, he pursued graduate studies in philosophy at the University at Potsdam.

His ongoing interests center on Jewish thought and its influence in postmodernism with a focus on deconstructionist Jacques Derrida, existentialist Emmanuel Levinas. poet Paul Celan, and Jewish American Abstract painters, Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman and Helen Frankenthaler.

Asked if there were parallels between his work and that of muralist aleXsandro Palombo, who has painted the Simpsons at the gates of Auschwitz, Kharchenko pointed out significant differences.

“I have never personified Jews at Auschwitz with cartoon figures,” he said. “We both use bright colors and interact with cartoons, but in the end my message is totally different. I am not a cartoonist, I am a painter and I paint pictures, which is far more sensitive and complex in expression than cartoons or street art. I use the beauty of painting and combine it with horror. I also refer to other war crimes like USSR’s totalitarian cleansings during the Stalin years, US war crimes, and lately the Ukraine and Israel wars.”

From trauma to Talmud and Torah

At the age of five, Kharchenko was already drawing and his parents recognized both his unusual skill and, more striking, his vivid and fantastic imagery that only grew with time and experience.

When he was 11, partly in response to antisemitism in Russia, the family emigrated to Germany.

“I was around 8 or 9 years old when my best friend in Moscow suddenly did not want to play with me anymore, saying that my family and I are Jews,” Kharchenko recalled. “Similar things happened at school. I was too young to understand what was going on but at some point it made me feel like an outsider.”

Still, he said, in Berlin an undertone of antisemitism was always present, even though he found that Germans generally took responsibility for their country’s Holocaust history.

“However,” he added, “Many people do not want to accept that the catastrophe of the Holocaust and the Second World War after 1945 brought with it a new spiral of violence and countless deaths. Many see the terrorist mass murder of Jews on October 7th and the Gaza war that Israel is waging today as outside their historical responsibility.”

In recent years, Kharchenko says he has seen antisemitism become more blatant especially in the art community, specifically, “its fanaticism with postcolonial theory and wokeness.”

“Personally I got many hate speech messages like ‘Israel doesn’t exist.’ ‘It was a mistake to found Israel.’ ‘As a German Jew, you’re only a temporary guest in Germany.’ ‘You benefit from German tax money and yet you present yourself in Germany as a victim,’” Kharchenko said. “Now antisemitism is coming more from Muslims. Luckily I personally have not been confronted with Islamic antisemitism but family and friends have experienced some hardcore incidents.”

He recalled an art professor who referred to his mom as a “f–king Jewish mother,” and later marveled that,”Kharchenko is a Russian Jew, but he is somehow a good painter.’”

“Students in the class made jokes about me being a Jewish artist and businessman because my paintings were sold at Art Cologne when I was 19 years old,” Kharchenko said. “A few months ago, after an exhibition opening, a former freelance journalist, who often wrote for Frieze and Art Forum, told me that ‘having real estate is a typical Jewish thing.’”

Kharchenko also recounted an incident in which Neo-Nazis physically assaulted him on the street, demanding money. “They screamed ‘Jew give us money’” he said. “They wanted to kill me. Luckily, I could run away.”

The trauma forced him to confront his understanding of himself as a Jew, made all the more complex because as a Russian-born Jew, religious observance had never been a part of his life. Nonetheless, he knew he was Jewish and perhaps at no time more clearly than when others were not only pointing it out, but berating him for it. For an amalgam of complicated, not readily definable reasons, he enrolled at Lauder Yeshurun Yeshiva where he studied Torah and Talmud. This too turned out to be an ambivalent experience.

“In the beginning I was fascinated by Talmud and Torah and Jewish ethics, which overwhelmed me,” he recalled. “It opened new layers of my identity and influenced my art. I was so happy to realize how great it is to inherit such a deep tradition. I was especially moved by how the intensity of Jewish prayers can affect the inner world and one’s personal transcendence. I started to pray in Hebrew, using the Siddur books I had inherited from my great grandfather, Some are more than 120 years old.”

But within short order he grew increasingly turned off by the restrictions, demands and bigotry expressed by some of his teachers. He was told, for example, that “art is not Jewish” and that he should steer clear of it. Further, he was advised to cancel his relationship with his non-Jewish Russian girlfriend; and informed that Gentiles are stupid and that moving to Israel was the only way to become a real Jew.

“This led me to break every Shabbat and paint on Shabbat,” he said. “Still I identify myself as a secular Jew.”

‘There was no Superman who rescued Jews from Auschwitz’

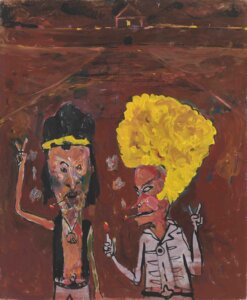

Kharchenko’s subject, tone, and style have evolved over time. Some early pieces merging representative and abstract forms centered on houses and windows and employed multiple layers of paint on canvas. Later, Kharchenko moved on to more figurative drawings including a series of portraits of the Medici family, Simon Wiesenthal, Jorge Luis Borges, Amy Winehouse and his own grandfather, an unusual man in his own right whose birth name was Grynszpan.

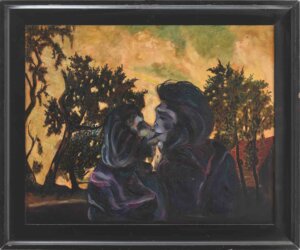

“He changed it to a typical Ukrainian name, ‘Kharchenko,’ while he served in the Red Army, in order to avoid speculation as to whether he was related to Herschel Grynszpan, who shot Ernst vom Rath, secretary at the German embassy in Paris in 1938,” Kharcheno said. “Grynszpan was taking a stand against the first deportations of Jews to Poland, which led to Kristallnacht. Nov. 9, 1938. I painted my grandfather again in 2023 as Superman in front of the gates of Auschwitz, together with his parents. I don’t want to mention the number of my family members who were killed by the SS.”

The Superman paintings are overflowing with irony, contradiction and continuity.

“Jerry Siegel, who invented the Superman figure, was Jewish,” Kharchenko said, adding that, “there was no Superman who rescued Jews from Auschwitz.”

“Though I painted my grandfathers in Superman costumes, they were real Supermen who fought from Stalingrad to Berlin and lost all their families,” said Kharchenko. “The paintings also refer to the bloody senseless Ukraine war today and the heritage of the Stalinist regime as well the corrupt totalitarian regime of Russia today.”

In more recent paintings, Kharchenko addresses the Oct 7 Hamas attack and the events that followed. Influenced by the work of Salvador Dali, he used elements such as watches, the IDF Star of David, and Cohanim hands to evoke the desperation felt on all sides as well as the sense that time is running out.

“I am happy if the viewer could experience similar feelings and reflections I had during the process of painting those works. I bet that almost all Jews on this planet could not really sleep after Oct. 7, cried after seeing the atrocities shown in the media and finally kept on questioning their own Jewish identity,” Kharchenko told me.

“For me being an artist means to react to worldwide events. Probably an artist would not exist, if the world was perfect. I have painted more than 150 paintings in the last 2 years on worldwide destruction. My art is a filter for self-expression. It is the silence of my grandparents that makes me speak and paint. There remains an emptiness and a sense of optimism and an endless desire for expression.”

Yury Kharchenko’s work will be featured in his upcoming solo show, “The Jewish Museum,” which will run June 29-Oct 20 at Hallische Frankisches Museum, Schwäbisch Hall, Germany.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO