All Roads Lead Back To Käthe Kollwitz

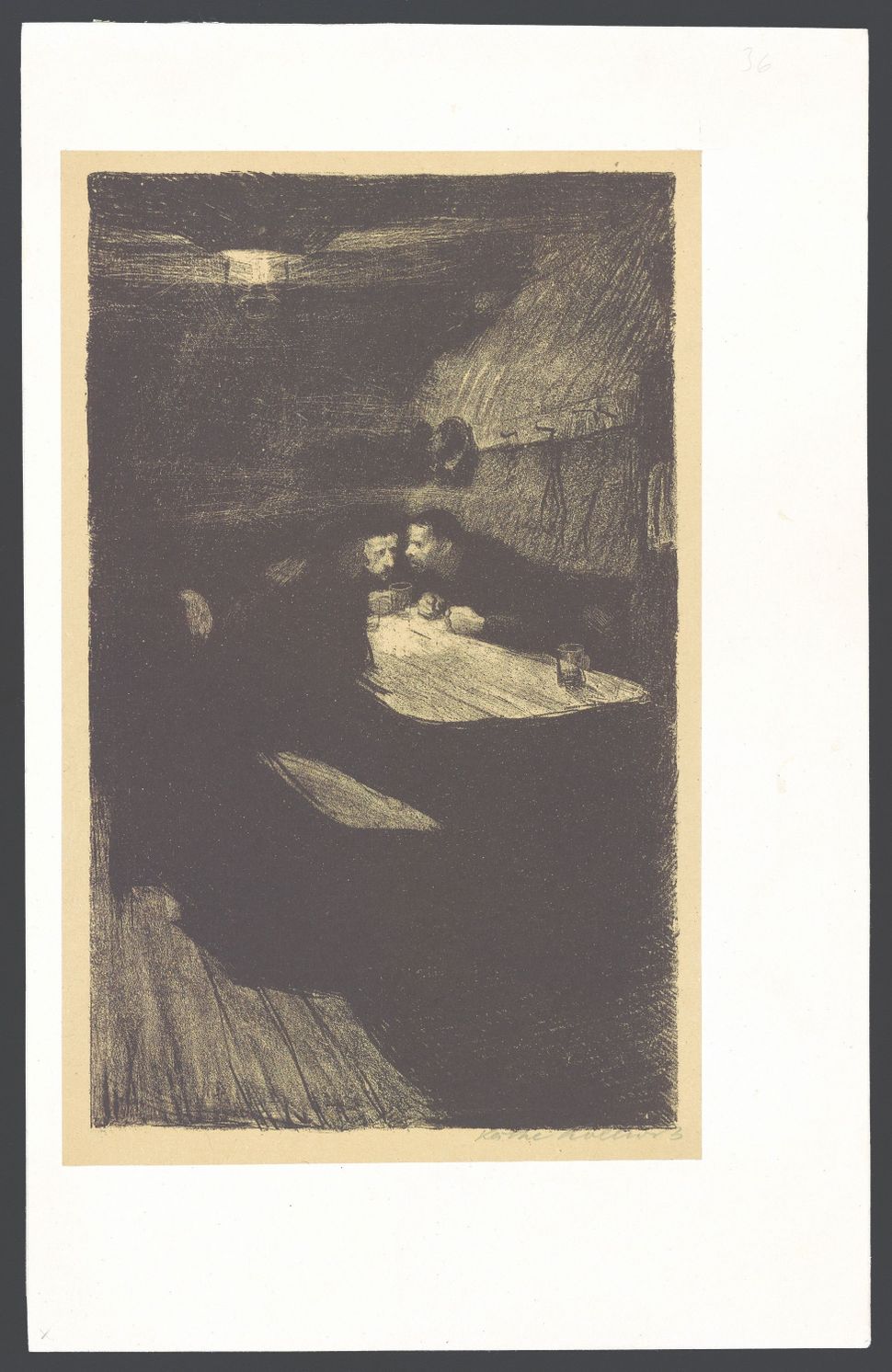

Conspiracy: Kollwitz drew a group of men plotting in a tight corner of a tavern. Image by Getty Research Institute Los Angeles

This is the third in a four-part series of stories about the work of Käthe Kollwitz and how it influenced artists, activists and collectors like Dr. Richard Simms, part of whose collection is being exhibited by the Getty Center in Los Angeles. You may find the previous articles here and here.

In 1971, as America churned with the social movements of the Vietnam era, a 26-year-old activist named Martha Kearns, living in a politically-committed urban commune in Philadelphia, wrote a proposal to a press newly formed to publish books about women by women. Kearns wrote what she refers to as Movement Poetry, but had never attempted a book before. She planned a biography of Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945), a German artist whose life of social engagement, existential ups and downs and creative ability, she said recently, offered a natural mirror to “the movements of the time, anti war, civil rights, also the Women’s Movement.”

She’d seen only a few of Kollwitz’s works, but had been “moved very deeply,” by the artist who was counted by connoisseurs, especially of works on paper and sculpture, among the leading artists in history. Activists and college students in the 1960s honored her for her anti-war images and art about the urban poor. Florence Rosenfeld Howe, a rabbi’s granddaughter whose Feminist Press became a beacon for its time, took the book “instantly,” said Kearns.

Kearns became the first — still, strangely, the only — English-language biographer to address the whole of Kollwitz’s life. In its last pages, Kearns placed a poem by the Jewish-American poet Muriel Rukeyser titled, “Käthe Kollwitz.” With fierce clarity, Rukeyser conveyed Kollwitz’s revealing realism about the world and herself, referring to her many self-portraits, and asking: “What would happen if one woman told the truth about her life?”

This fall, starting on a sunny October morning from New York’s Penn Station, I started to travel to talk with women and men who’ve been especially inspired by Kollwitz. Rukeyser is gone, but I wanted to hear the voices of other writers and artists who I felt might offer a better understanding of her through their eyes.

My final destination, as I write this, will be an exhibition at the Getty Research Institute (GRI), part of the J. Paul Getty Center above the 405 Freeway in Los Angeles. The show — “Käthe Kollwitz: Prints, Process, Politics” — will unveil the collection of Kollwitz works built by Dr. Richard A. Simms that the GRI acquired in 2016. The show of about 100 works (from a total of 654 Kollwitz and Kollwitz-related works Simms collected) is set to open on December 3. It will be the most comprehensive exhibit of Kollwitz’s work in this country since 1992. After Los Angeles, many of the works will travel to the Art Institute of Chicago.

The impulse to hit the road for this piece grew when I was talking with the late Hildegard Bachert, a German Hitler refugee who became a leading dealer of Kollwitz’s work at New York’s Galerie St. Etienne and a friend of Simms. Bachert, then 97, spoke to me that day of the large community of the artist’s devotees, declaring: “Kollwitz people are nice people.”

I’d studied the Kollwitz world enough to know that “nice” had a bigger meaning. Civility is part of the Kollwitz-admiring character. But the word also embraces an artist who responded to the Judeo-Christian Humanist tradition by translating it into secular values. She didn’t teach good conduct, but her skills at turning her instinctive empathy into visual reality set an example in life and art. What follows, are meetings with four such people, including a German-born master puppet-maker who told me how his sense of Kollwitz as an artistic witness connected to his having watched, at 10, a horrific attack in World War II. Another is one of America’s most outstanding print-makers, who explained that she was mindful of Kollwitz’s approaches to the art form they shared when making work inspired by the writings of Franz Kafka. I met a painter from China who revealed that Kollwitz exerted an influence in that country that gave an unintended open view to young Chinese artists under a repressive regime.

The universalist emphasis in Kollwitz’s art gained a second life in how the Kollwitz people I met skipped blithely over distinctions between themselves and others, finding a place where a specific artist’s work speaks to a wide range of people. They told of how their attachment to her was built on differences of religion, race, ethnicity and nationality — but also transcended them.

Kollwitz people tend to live with a lot of music—especially Bach. It became a repeated patch in my crazy-quilt of encounters with fervent people, a journey that started on October 15th, when I boarded Amtrak’s Northeast Regional train in New York’s Penn Station for Philadelphia.

City of Sisterly Love

Biographer of Kollwitz: Martha Kearns, seen here with a mask at an exhibit of artwork by contemporary Nigerian painter Wole Lagunju, is the author of “Kathe Kollwitz: Woman and Artist.” Image by Allan Jalon

Kearns picked me up at my hotel in the Center City section of Philadelphia. She’s an ebullient 74-year-old woman who stands just over five feet, with pale blue eyes and a propulsive energy that persisted as she drove us through a dense rain and morning traffic.

In her beige-ish (“I call it my golden chariot!”) Honda Accord, we headed off on an hour-and-a-half drive to Moravian College in Bethlehem, PA, where she teaches art history, to see an exhibit of paintings by Wole Lagunju, a contemporary painter from Nigeria that she helped to curate.

As she drove, she moved from describing the “strong social overtones” of Lagunju’s art, to recounting the two experiences that led her to write her book, “Käthe Kollwitz: Woman and Artist.” The first was working with Peter Schumann, the founder of the Bread and Puppet Theater.

Schumann, who recently turned 85, arrived in this country from his native Germany in 1961, having been born a year after Hitler took power and growing up during the war. His dynamic puppet performances drew on European street theater and the Humanist tradition to protest, in startlingly imaginative ways, the traumas of war and race in 1960s America.

Between 1969 and 1971, Kearns made masks and performed with Bread and Puppet, becoming part of a tour through the American South to perform at coffee houses near military bases where soldiers were turning against the Vietnam War.

Schumann, she recalled, spoke of Kollwitz’s impact on him. Kearns said she connected her early feeling for Kollwitz to a Schumann piece called the “Grey Lady Cantata II,” and a short film of it that survives shows a haunting group of war widows — tall, grief-stricken puppets echoing grieving mothers who Kollwitz had re-imagined in various forms after her son, Peter, was killed in World War I.

“I found myself thinking about Kollwitz a lot in that time,” Kearns said, “after hearing of her from Peter and seeing how his work was definitely Kollwitzian.”

For her and others enveloped in social causes of the time, she said: “We were seeking positive imagery of what we were involved in. We wanted Kollwitz’s art. We were hungry for it. We were trying to create a just world.”

In 1970, she saw a Kollwitz print called “Mary and Elizabeth” in a counter-culture magazine. It showed two pregnant women talking with a closeness that transcended social contact.

“That is it,” she said, as I opened a book of Kollwitz prints, sitting in the passenger seat, trying to hold it steady. “But that’s the lithograph. I saw the woodcut. She did it three times. The woodcut was darker, and what I saw in that Movement magazine was the woodcut.”

Kollwitz people tend to bring to the artist a visceral, tactile eye for the deep contrasting blacks and white she used, and her dramatic shadings between extremes.

“What struck me was that it was very tender and very reverent,” Kearns said. “It was only later that I learned it was religious — secular but religious underneath. What I liked most about it was the blackness, even in the mimeographed reproduction of that magazine.”

Kearns writes in her book about where Kollwitz got her idea for the print: The artist was “greatly moved” by a painting she’d seen at a museum of two pregnant Biblical women, future mothers of Jesus and John the Baptist.

The diary describes the two women as standing “facing one another” holding cloaks they wore open, so that “in their swollen abdomens you see the coming children…”

Kearns wrote of the final, 1928 woodcut as “a visual poem of caring between women.”

Soon after starting her research, Kearns reached out to Hildegard Bachert. “I was young, but Hildegard believed in me,” Kearns said. “She took out all the Kollwitz books she had, between 10 to 20 books. Most were in German. I couldn’t have done the book without her.” The book, published in 1976, was a big seller for the Feminist Press. It sold 17,741 copies, a number Kearns has memorized, even as she reports the book is out of print. It was seen on shelves in many college dorm rooms where cheap copies of Kollwitz prints hung on walls. Artists kept well-thumbed copies in their studios.

Her book, sometimes reviewed along with a shorter biographical study that appeared a year before, was generally well-received when it appeared in 1976. Feminist critics praised it, as did others with social and anti-war views that then drove much of the cultural dialogue.

One reader, Kearns told me, was the late print-maker and sculptor Elizabeth Catlett who Kearns once referred to as “The American Kollwitz.” The highly-regarded Catlett, who was African-American and spent much of her creative life in Mexico, studied Kollwitz’s work and spoke of her feeling for it to Kearns through the years they knew each other.

Kearns said Catlett had told her about the Guerilla Girls, the group of women art activists who continue to seek greater recognition for women artists and roles for women in the art world. One of the Guerilla Girls, who take on the names of women artists they believed are under-recognized, calls herself Käthe Kollwitz.

We finally reached Moravian College’s Payne Gallery, where a number of actual Yoruban tribal masks were showing together with Lagunju’s strong, deftly ironic paintings. The Nigerian-born, North Carolina-based artist paints versions of portraits that glorified the wealth and power of European aristocrats in the so-called Golden Age of Discovery — but with an understanding of the oppression and theft that fueled it. Faces from African tribal masks appear where the European faces would have been.

As we toured the show, Kearns told me the show reflects her efforts to steer students to artists from different backgrounds. Kearns, raised Presbyterian, is very active in an Episcopalian church and previously headed what she called a “faith-based arts ministry” associated with the Methodist Church.”

“Christianity has always played a part of my life but I am a charter member of a Hadassah chapter in Center City,” she said, laughing. By the time Kearns drove me to Philly’s Union Station, still as energetic as at the start of our day, I wanted to learn more about the link between Peter Schumann’s puppetry and Kollwitz. I’d admired his artistic-activist vision since college and I wanted to meet him and hear him speak about what his art gained from hers.

A few days later, I boarded another Amtrak train and took the eight-hour ride to Vermont.

Cheap and Intense Art

Magic Bus: This red school bus heralds your arrival to the Bread & Puppet compound, founded by Peter Schumann. Image by Allan Jalon

The day after arriving in the Green Mountain State, I drove into its northeast corner. Outside the small town of Glover, I turned up a hill and kept climbing until I saw a red school bus that had been converted into a roadside shop for prints, drawings and posters. Big colorful letters painted on the front advertised: Cheap Art Store.

I’d reached the Bread and Puppet Theater’s loosely arrayed compound.

The bus’s cheerful offer was a Kollwitz-like message. Working with mass-market printers, she made versions of her art that were inexpensively accessible to the largest number of people. Dr. Simms and other collectors spend a lot of money in pursuit of rare and process-revealing pieces, but many Kollwitz people are drawn to her populist side.

Schumann, the Prospero-like conjurer of Bread and Puppet, the man in whose presence Kearns had felt enveloped by Kollwitz thinking, also made some of the prints sold in the bus. Most are priced at under $20. He makes his group’s performances as close to public events as possible. Free bread is handed out to audience members.

After he opened the door of a sturdy old house, he told me he recalled Kearns well, then pulled out a book about the Bread and Puppet’s history by Stefan Brecht, the son of Bertolt Brecht, with photos of the “Grey Lady Cantata II” and other pieces he said Kollwitz had influenced.

It was lunch time, and Schumann and his wife, Elka, shared a bowl of their lentil soup. He pulled out a fresh-baked loaf of sourdough rye bread so essential to the Bread and Puppet’s identity. His mother had made bread like this, he told me, in his still-clear German accent.

It was a peasant food universal among the German working classes. He said he was sure Kollwitz had just such bread in mind when she made a poster decrying Depression-era hunger.

It was, he said, the first image of hers he saw just after World War II.

“Brot!” he said. “She put that word on her poster, together with the starving family.The way she combined words with the image for that poster is something I have done in my work.”

Indeed, the combination of visual and verbal experience — also music, sometimes Bach—are as basic to Schumann’s theater pieces and the prints he makes as the bread he ate as a boy.

He described the “war-waging, war-ravaged” Germany where he was five when Hitler’s troops entered Poland in 1939. He came of age in the middle of Allied bombings and told how his family fled them. Among his most dramatic memories was how, at age 10, he watched from a bluff overlooking the Baltic harbor of Lübeck as Allied planes sank the SS Cap Arcona, a German ocean liner that carried both German soldiers and inmates of concentration camps.

The well-documented accounts of the Cap Arcona sinking in 1945, a complex attack that is not well-recalled today, describe one of the most grotesque events of the time.

“I was with my brother, and we were supposed to be inside where it was safe. But we were up on a hill above the harbor and we stayed and watched,” he said. “We were boys and we should not have been there, but we couldn’t pull ourselves away. The next day, the bloated bodies of the victims washed up on the shore. They washed up for days.“

Was his art influenced by his war-time experiences, I asked.

“Absolutely,” he said. “That’s how an artist works, I guess, all that garbage from your life ends up inside of you and it ends up in your work.”

Kollwitz’s work about war-time suffering has long exerted its power on him, he said.

Schumann, who said he first began to closely look at Kollwitz’s work in a museum in the city of Hanover toward the end of the 1940s (it had been banned during the Nazi era) seemed to grow more sharply alert to those memories when he told me about one pose he’d seen in several of her pieces.

“This,” he said, suddenly wrapping one arm over his head and putting a hand over one eye: “This wrapping of herself and holding herself.” I’d seen Kollwitz self-portraits and other works reminiscent of this pose gesture, especially the eye-covering hand. My parents had owned a lithograph with the artist closed into herself.

“What is this wrapping, this self-wrapping, to you? What is she expressing?” I asked Schumann.

“The brain is falling out of your head and you must hold in the pieces,” he said. “One eye is closed in sorrow.”

“Because your experience has been so extreme?”

“Yes,” he said. “This gesture — it is an element of our time. I mean my time and Kollwitz’s time. It is a time you are in and you can’t get yourself out of it. It was her time, but we are impressed, when we see it, by the fact that the human situation is not resolved.

“You would have thought that, after the Nuremberg Trials, after they hung the Nazis, that it would have ended,” he added, in a mournful tone. “But then, people started war-mongering again in the Cold War, removing themselves again from what it meant to be human.”

Bread and Kollwitz: Bread & Puppet founder Peter Schumann holds a loaf of bread and a picture of Kollwitz’s “Brot” poster. Image by Allan Jalon

Schumann led me down the hill from his house to a large barn that serves as a museum for puppets from his plays and pageants. Filling the cavernous interior, which is like a cross between a huge haunted house and Noah’s ark, are countless puppets made of paper maché and other materials of all sizes and shapes. Their faces express political rage, ecstatic celebration, and lamenting sensitivity.

One corridor was given to puppets and other props from Schumann’s drama about the life of Charlotte Salomon (1917-1943). The Berlin-born German-Jewish artist created her masterpiece, a sprawling work of hundreds of visual pieces, while in hiding from the Nazis.

Schumann’s work follows her from childhood through her death in Auschwitz, in 1943. Schumann, who says he grew up “Lutheran-atheist,” has also created works that are critical of Israeli state power in its treatment of Palestinians. He has been strongly criticized for these works, but he told me that, while he regrets offending people’s feelings, he has always risked controversy. “I won’t stop,” he said,

He pointed to the grieving mothers from the work from which Kearns felt gave her the first spark of Kollwitz interest. He gestured to another group of figures high on a wall, which he said appeared in a 1982 piece called, “The Thunderstorm of the Youngest Child.” They had hands wrapped around their heads, pressed to their eyes, the pose he’d enacted.

“Kollwitz?” I asked.

“Kollwitz,” he said. He pointed at other such figures: “She’s there.”

“Kollwitz, but also Rodin. And Michelangelo. There’s a lot of Michelangelo jumping out all over the place in Kollwitz.”

Kollwitz Meets Kafka

Only a Doctor: A 1962 lithograph shows the influence of both Kollwitz and Kafka. Image by Claire Van Vliet

On another rainy day, I took a drive amid the mountains and lakes of Vermont to visit Claire Van Vliet.

The coming year will mark 65 years since Van Vliet founded Janus Press, naming it for the Roman god who could see both the past and the future. She will also celebrate three decades since she received a so-called “genius grant” from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation.

The best way to understand the extent of her varied achievements is to look at a catalogue that carefully details the press’s multi-layered history, published by the University of Vermont Libraries.

It tells a story about the artists, authors, and translators who have worked with Janus since she started it. Since 1966, she’s lived in the tiny Vermont town of Newark. The press has published or co-published over 90 books, more than a dozen broadsides and other work.

The Canadian-born Van Vliet, 86, is highly regarded for what she calls her “wall art,” drawings, prints and pulp paintings, appending pigmented paper pulp onto a handmade paper underlayer to form an image. As a print-maker, she’s worked across traditional techniques that Kollwitz pursued—metal plate etchings to lithography to woodcuts.

I found, in a catalogue occasioned by an extensive 1999 show of Van Vliet’s work that traveled in New England and elsewhere, an interview in which she notes the impact of several artists. “Käthe Kollwitz was the greatest influence for me on how to approach form, particularly in the medium of woodcut,” she said.

Artist And Inspiration: Claire Van Vliet poses with a Kollwitz Print. Image by Allan Jalon

Van Vliet lives on a high hill, beside a long, unpaved road and across from a rust-colored mailbox. Woods beyond her grey salt-box house darkly frame a wide-open field, a contemplative setting for a studio with large windows and broad tables for a printer’s work.

A grey, rainy-day light filtered into the space as we sat and spoke of Kollwitz, whose art Van Vliet said she first studied as an art history student at San Diego State University in the early 1950s.

Van Vliet leapt up and returned with a Kollwitz print— “Conspiracy,” the third image (of six) from Kollwitz’s first print cycle, “A Weavers Rebellion,” about a strike by Silesian fabric workers. In the intricately etched print, several men sit at a table in a tavern to plot against their bosses.

Van Vliet found the print in a store in Claremont, CA, in 1952, and said she was so openly moved that the owners gave it to her as a gift. What got her attention?

“Those two forms.” She pointed at the firm-looking, rectangular brightness of the table and the bright long plank of the bench on which the plotters sit. The print embodied the formal strength of how Kollwitz often built contrasts of light and dark, Van Vliet noted.

Van Vliet, raised in the Anglican Church, said she discovered Franz Kafka’s writing in 1961. Spending time in Montreal, subletting a house from a reporter for a Jewish publication who was spending time in Israel, she found his books on a shelf, and was captivated. The Jewish writer from Prague, with his sometimes terrifying, always probing search through consciousness became a catalyst for a lot of her work as both artist and publisher. Her prints and drawings of landscapes in Vermont and elsewhere distill a unique balance of power and delicacy. Still, Ruth Fine, a former curator with the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. has described her 30 or so black-and-white Kafka pieces as an “essential part of her output.”

“Kafka seemed to me, in a very clear way, to portray the state of mind after the Second World War,” Van Vliet said. “Of course, he was writing before that, but it was such a wake-up call for everybody—his whole approach, his sense of futility and of the unexplained world was very powerful, and he really spoke to me.”

Van Vliet showed me “Only a Doctor,” a print that was influenced by Kollwitz as she lllustrated “A Country Doctor,” Kafka’s very unsettling story about a physician who goes to cure a patient with a dramatic and ambiguous wound.

The story culminates in a scene in which the doctor proves useless at his job and stands naked in front of the uncured victim of fate as he lays still with a blanket tucked up to his still chin. The shadows stir with the bristling figures, in Van Vliet’s print, of a vengeful crowd.

The tautly emotional energy that Van Vliet’s work gives to Kafka’s scene owes a clear debt to a woodcut Kollwitz made to honor to Karl Liebknecht, the slain leader of the German Leftist revolution of 1918-1919.. In it, Liebknecht’s working class mourning followers surround his corpse.

“The Liebknecht Memorial was very important to me for how to cut, how to approach the form with the knife,” Van Vliet said.

Longest Road Through Kollwitzland

‘Charge:’ In this line etching, dated 1902-03, Kollwitz depicted a scene of rebellion. Image by Getty Research Institute Los Angeles

In Montpelier, I stayed in a hotel across from Vermont’s gold-domed statehouse, and read about the city. It was an early hub for Northern New England roads that stretched up into the hills and across dozens of river-crossing bridges. Rt 2 takes you northwest to Lake Champlain in one direction and all the way to Bangor, Maine, in the other. It’s not far to Canada.

By phone, one morning after breakfast, I traveled far across the Vermont state line. Beijing was having dinner at that point, 10 hours ahead, when I rose at 7 am to call a painter named Tian Wei. We’d met two years before at the Getty Research Institute in LA,, where he was an artist in residence. In a soft voice, the lanky artist with a grey-black pony tail had spoken a startling sentence.

With the roads of Montpelier quiet, I called him to hear it again. From across the globe, he obliged: “Käthe Kollwitz was the most significant Western artist for my generation of Chinese artists.”

“We grew up in the harsh Cultural Revolution,” explained Tian Wei, 64, who lived for years in the United States before his recent return to China. “We were only allowed to appreciate certain kinds of artists. She was one of the ones they (political powers) supposed to be a Western example of Social Realism, which they approved of. Her art came out of this revolutionary kind of thing, but she was doing much more than that, and we could see it. Her art was so strong as art. If you see one of her prints, it is imprinted on your mind. It jumped out at us.

“We began to look at her in a way that was not expected of us,” he added. “She wasn’t what they thought she was when they let us see her. No one had her impact on us.”

I asked: “Not even Picasso?”

“He was not permitted. Mainly, just Russian artists.”

Tian started out making figurative art, but became passionate, after arriving in New York in 1986, about Abstract-Expressionism. He explored how traditional Chinese calligraphy and Modernist abstraction could work together, creating his approach today. He acknowledged that, as they look now, his paintings don’t reflect Kollwitz’s stylistic influence. But he said that limiting her impact on him by focusing only on outward appearances would overlook the basic feeling he drew from her:

“Her images are very strong. We responded to this strength in her and we found we could use her influence, her art work, as an example of strength for any kind of art.”

Brattleboro

Kollwitz’s ‘Death’: The artist used a scratch technique for this late 19th Century lithograph. Image by Getty Research Institute Los Angeles

Heading to the southern edge of Vermont, my train stopped in the town of Brattleboro and waited a while amid the fiery colors of a sunny late-October day.

When imagining my trip, I’d hoped to get off there. It was where Bachert had a country home, living among family and friends. She also had an apartment in New York, where she lived as she worked with Jane Kallier, the director of the Galerie St. Etienne during their many years as its co-directors. Last year, at 97, Bachert retired from the gallery and moved full-time to Vermont.

I’d never been to Brattleboro and wondered about Bachert’s country life. I was checking the Amtrak schedule for an overnight stop to visit her before heading farther north into the state, when I got an email from Jane Kallir, telling me that Bachert had died there on October 17.

Her death came as the Galerie St. Etienne was showing the second of three exhibits to celebrate its 80th anniversary. It focused on dealers, like Bachert, who also formed an unusually rich scholarly grasp of artists they represented, and the gallery’s walls held some superb Kollwitzes.

At the gallery’s front desk, one can pick up a copy of Bachert’s biography published by the St. Etienne, which contains a story that follows the general outline of Jewish flight to America as a refugee from Fascism. Like so many, she found haven here but never forgot where she came from.

The memoir’s chapter about her childhood in the city of Mannheim describes her widening awareness of nature and culture (she and her family collected postcards “by artists like Kollwitz”) and then a massive blow on the anvil of history that pulled her world apart:

“The Nazis came to power in 1933, when I was hardly twelve.”

She arrived in New York in 1939 and started at the St. Etienne in November, 1940. Otto Kallir, Jane’s grandfather, had founded the gallery in 1939, the year he also arrived in New York in flight from the Nazis. She played essential roles as the St. Etienne grew into a leading place for art from German-speaking countries. It also pioneered the sale of work by Grandma Moses and other artists. When the Kollwitz collection of Dr. Simms becomes a public exhibition in a few weeks, it will have developed to a notable degree from the relationship between Dr. Simms and Bachert. The St. Etienne sold 69 of the works to Dr. Simms, and he has spoken of how much Bachert taught him about Kollwitz.

He traveled from California to Brattleboro to visit her three times for Passover, he told me. After she retired, he put in a standing order with a local florist to send her flowers once a month, wanting to brighten up her Vermont winters.

As she said, Kollwitz people are nice people. But, again, the word as it applied to her and Dr. Simms went farther.

One wall at the GRI show will include a unique drawing Kollwitz made as she developed a print called, “Das Volk,” or: “The People.” She was working on the seventh image from “War,” a Kollwitz cycle from the early 1920s.

She made several efforts to complete the work, another time the artist seemed to enter a wilderness of possibilities and fight for clarity about her destination.

The drawing, in brush and black ink with white wash and charcoal, shows a group of lost-looking souls in a dark void, wandering. An old woman stares out, directly at the viewer.

She looks much like Kollwitz herself, her eyes open and steady, with an unyielding focus on some kind of serious truth that lives both in herself and the viewer.

Beneath the picture, the wall text will read: “Gift of Dr. Richard A. Simms in honor of Hildegard Bachert.”

“Käthe Kollwitz: Prints, Process, Politics” opens at the Getty Center on December 3, 2019. It runs through March 29, 2020.*

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO