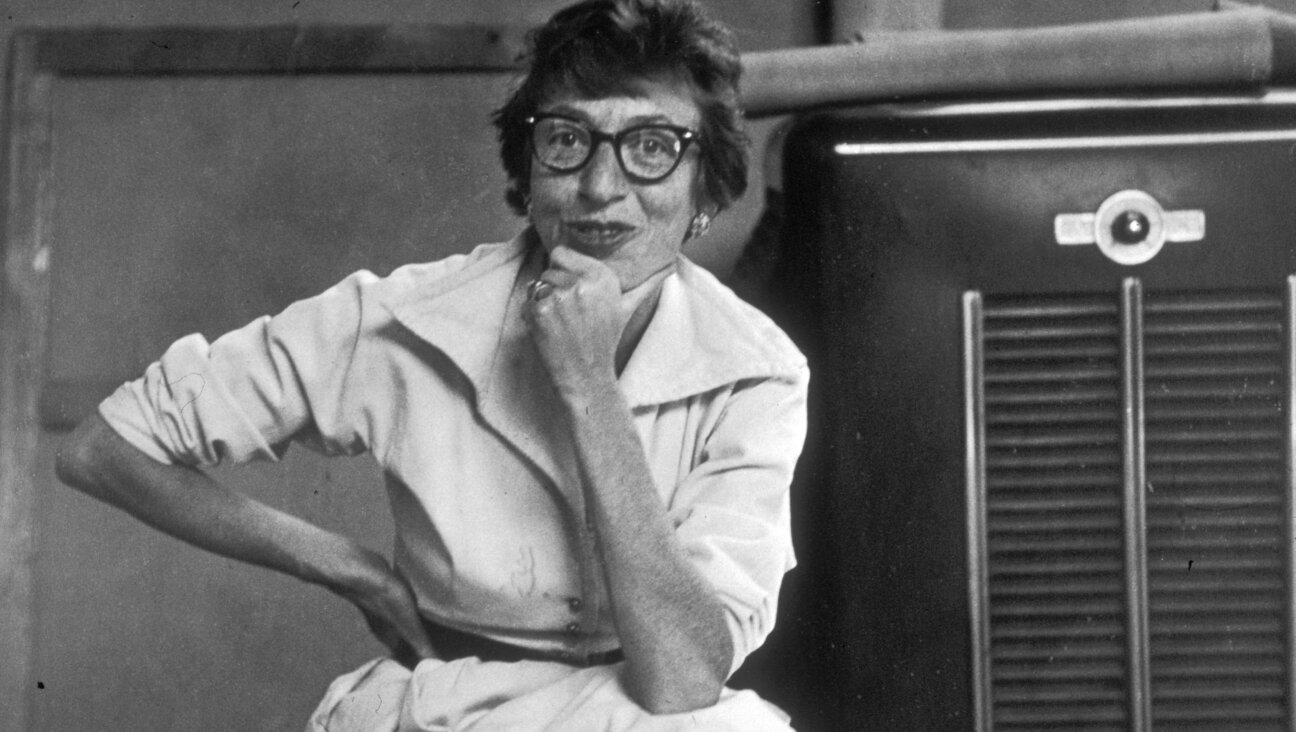

To Diane Arbus, Every Portrait Was A Self Portrait

Diane Arbus photograph of two women walking in Central Park. Image by Copyright Diane Arbus Estate/Courtesy of Lévy-Gorvy Gallery

AT first glance, Diane Arbus’s parks look like our parks — and yet they stand apart from them. What might a Martian learn about us from this, people sometimes ask of a text. Arbus’s photos would tell a Martian little: They rather look as though they may have been made by one.

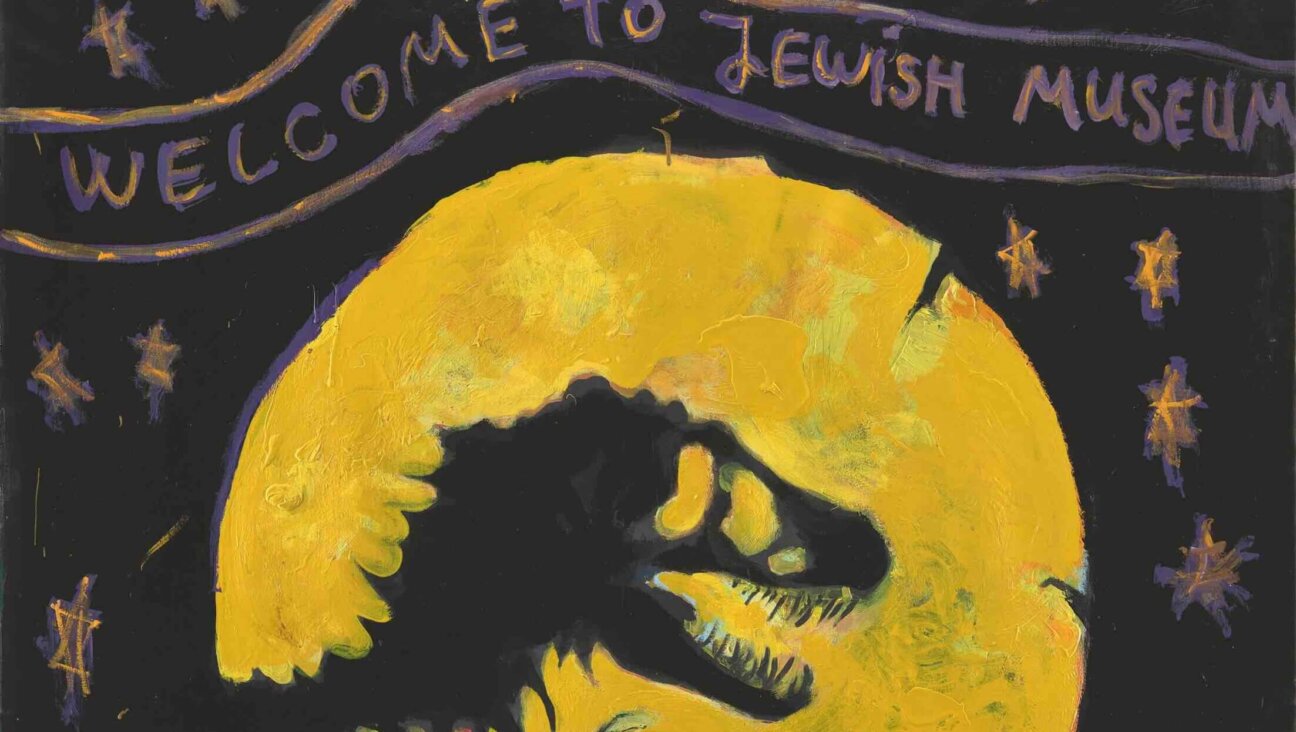

‘In the Park,” the Lévy Gorvy Gallery’s exhibition of Diane Arbus photographs taken in Central Park and Washington Square Park, follows by only a year the survey of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Met Breuer survey of Arbus’s early work, “In the Beginning.” Several photographs from the Met exhibit, most notably the indelible image of the “Child with a toy hand grenade in Central Park, N.Y.C., 1962,” appear once more at the gallery. The echoes and the temporal proximity serve only to reinforce the power of Arbus’s imagery, to reiterate the possibility and promise of seeing anew with every encounter. It may be the sheer strangeness of the work, its otherworldliness, its quality of an elegiac estrangement from everyday life.

What makes Arbus’s work so compelling — one of the things that does, anyway — is the way the photographer is so completely captured by what she captures. Recalling her time in Washington Square in “about 1966,” Arbus noted the park’s divisions, the territories occupied by “young hippie junkies,” by “really tough amazingly hard-core lesbians,” by winos and by girls looking to lose their innocence: “It was really remarkable. And I found it very scary… I got to know a few of them. I hung around a lot… I was very keen to get close to them, so I had to ask to photograph them.”

The resulting images are at the same time public and private, the park serving as stage and dressing room, a place where identity is performed and practiced. The people we encounter in Arbus’s pictures are open and clandestine, and the forthright titles — “Two Friends in the Park, N.Y.C., 1965”; “Woman on a Park Bench on a Sunny Day, N.Y.C., 1969” — manage to suggest how much and how little we know about those we see day in and day out as we perambulate around the city. With the parks as backdrops, Arbus captures the pastoral aspect of everyday urban life, a kind of Forest of Arden, where city dwellers escape the rigors of their routines and assume a kind of freedom from work and commodity and capitalism, though not from the haunting inevitability of death. (Please accept your reviewer’s apologies for being a bit of a killjoy.)

In “Child running in the park, N.Y.C., 1959,” a little girl, her arms spread open, runs toward the camera, as though anticipating takeoff. It is fall: Leaves rustle on the ground in her wake. The girl thinks it is still summer, but the viewer knows better. Reviewing Arbus’s 1972 retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, Susan Sontag condemned what she saw as Arbus’s pitilessness toward her subjects: “The ambiguity of Arbus’s work is that she seems to have enrolled in one of art photography’s most visible enterprises — concentrating on victims, the unfortunate, the dispossessed — but without the compassionate purpose that such a project is expected to serve,” Sontag writes in “Freak Show,” which appeared in The New York Review of Books. She cites Arbus’s own description of her aesthetic — “You see someone on the street, and essentially what you notice about them is the flaw” — and proposes that the “insistent sameness of Arbus’s work… suggests that her sensibility, armed with a camera, could insinuate anguish, kinkiness, mental illness with any subject.”

And it’s true. Arbus’s images have a certain “insistent sameness” to them. But that sameness is the searing stamp of her vision, a quasi-autobiographical portrait. Whatever else a picture by Diane Arbus shows, it is first and foremost a picture of Diane Arbus. Here, try this experiment: Climb to the gallery’s second floor and check out the portrait of Sontag and her son on a bench in New York City in 1965, which is being shown for the first time. It’s impossible not to recognize Sontag’s trademark look, and yet it is only the second thing one notices. Before it is a picture of Sontag and her young son, it is a picture made by Diane Arbus, a record of someone she saw as only she could see her.

“In the Park” is a reminder that Diane Arbus, the daughter of a prominent Jewish family, a department store heiress whose external life was enviable, and whose inner world was an apparently barely contained chaos and collapse, once wandered the parks of New York and took pictures of the people who caught her fancy. She never looked away. In this polarized, miserable, freakish time, we shouldn’t either.

Yevgeniya Traps writes about art and books for the Forward.

‘Diane Arbus in the Park’ is currently showing at the Lévy Gorvy on 909 Madison Avenue in Manhattan.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO