From plague times to Trump’s executive orders, Jews and immigrants have been accused of spreading disease

Trump is expected to issue an order would term migrants public health threats to rationalize closing borders

President Trump, signing one of many pieces of anti-immigration law he has said his administration plans. Courtesy of Getty Images

The Trump administration is expected to issue an order labeling migrants as a public health risk to Americans. According to reporting from CNN, the order is likely to invoke Title 42, the emergency public health authority, to restrict immigration across the U.S.-Mexico border, based on unproven claims that migrants carry tuberculosis and measles, as well as potentially the flu, scabies and respiratory illnesses.

Blaming a minority group for disease is, of course, a time-honored way to build prejudice, stoke hatred and dehumanize people. Once people fear for their own health, it’s easy to get them to agree that any supposed threat has to be kept away.

The sneaky thing about this strategy is that it is often a self-fulfilling prophecy. Plop all of your Jews in overcrowded ghettos with little food, medical care or even basic sanitation, as the Nazis did, and diseases like typhus will spread. And then it’s easy to point at the Jewish ghetto ridden with typhus and argue that the separation was necessary because there is something fundamentally less human, and fundamentally dangerous, about the Jews in the ghettos. (In fact, the Warsaw ghetto actually beat back typhus, thanks to community education done by Jewish doctors imprisoned there; the disease wasn’t eradicated, but infection rates fell even as conditions worsened.)

This was not, of course, the first time Jews were blamed for disease. During the Black Death in Europe, Jews were rounded up and burned because villagers believed they had poisoned wells or worked black magic that caused the plague. The issue then was that no one knew how disease spread at all, and it was easiest to blame a minority group with foreign practices.

You might think that this kind of rhetoric wouldn’t work today; that, since we know about germs and transmission, we know better than to blame specific groups of people, whether immigrants or Jews, for spreading disease.

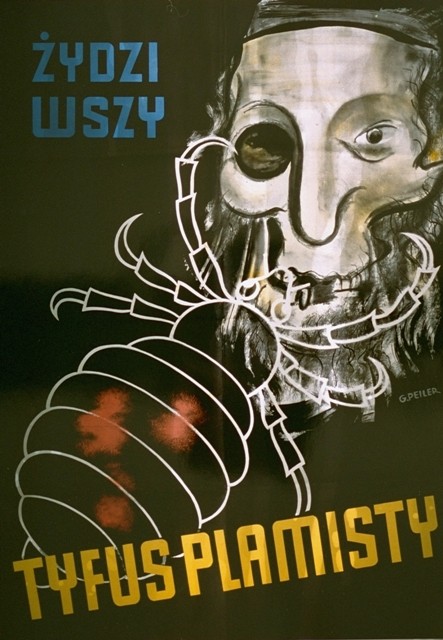

But during World War II, they did know that typhus was spread by lice, not people of any ethnicity. And people knew that lice thrive in crowded, dirty conditions. Yet this did not dissuade the general public from believing Jews spread typhus; instead, the propaganda leveraged the connection between lice and typhus to further denigrate Jews. Posters saying “Jews are lice, they cause typhus,” and superimposing a giant louse over a Jew blurred the distinction between the real cause of typhus and the scapegoated Jews.

This also worked because the Nazis had been rhetorically presenting Jews as parasites for years as part of a project of dehumanization, claiming that Jews took advantage of German society’s culture and success and spread moral depravity. With this mentality already well-established, it was a small jump to believe that Jews were not only parasites in a philosophical sense, but also in a literal one, spreaders of disease both moral and physical.

Trump has been using similarly denigrating rhetoric about migrants for years, referring to them as “animals” and alleging that they came from “insane asylums and mental institutions.” Now, he has sent a group of detained migrants to Panama, where they have been detained in a hotel and some have been deported to a fenced-in camp in the jungle. There, illnesses like dengue fever are endemic. And, though Panama’s deputy foreign minister said that the migrants have access to food, water and medical care in the camp, one detainee told The New York Times that all he was given was a stale piece of bread upon arrival to the camp, which doesn’t inspire confidence in the other resources supposedly available.

As journalists continue to track these migrants in the hotel and camps, letting the world know of their condition, we’ll know if they fall ill. And if and when that happens, the Trump administration may well present it as confirmation that they were right about migrants spreading disease.

Trump leveraged fear of disease to stoke xenophobia and hatred of migrants in his first presidency as well, invoking the same emergency health authority he is expected to invoke during his second term. During the early days of the coronavirus pandemic, Trump referred to the illness as the “kung flu” on numerous occasions, stoking already rising anti-Asian racism. And as the U.S. public began to panic over the pandemic, he closed the borders, drawing accusations from immigration advocates that he was exploiting the virus to scapegoat immigrant communities and support a xenophobic agenda.

The diseases the new public health guidance is likely to pin on migrants are already spreading in the U.S.; Texas is in the midst of the largest measles outbreak in over 30 years. But this is likely due to low rates of vaccination, not immigration; as the measles cases have risen, border crossing rates have fallen.

Yet as Trump prepares public health guidance blaming migrants for the spread of disease, he’s also taken away one important piece of infrastructure on the border: health inspectors. As part of massive federal layoffs, hundreds of health inspectors who screen people, plants and animals for disease before allowing them to enter the country received notice that they had been fired last week, leaving some of the CDC’s 20 port of entry health stations entirely unmanned for the foreseeable future.

After all, whether or not migrants are actually spreading disease isn’t relevant if you decide to keep them all out.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO