Anne Frank didn’t live here — she never had the chance

A full-scale recreation of the ‘Secret Annex’ opens in New York, a place the Frank family sought vainly to reach

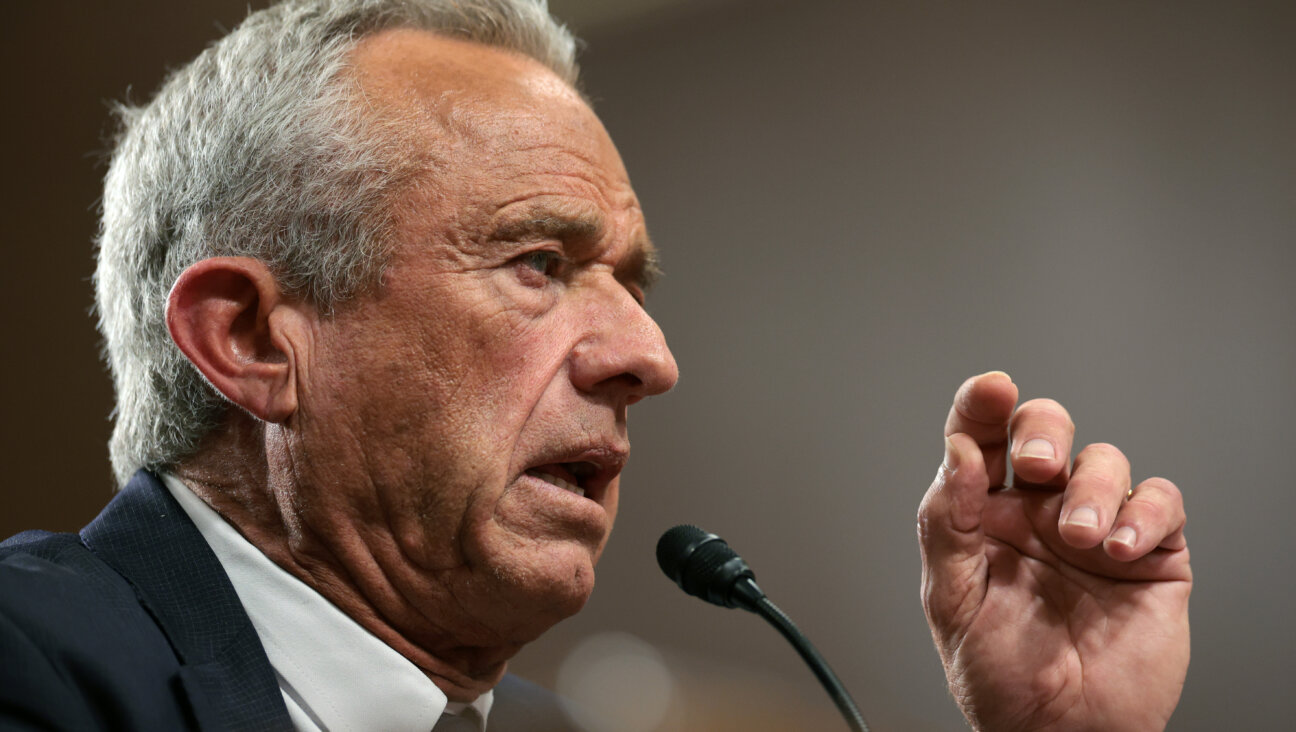

A person looks at a picture of Anne Frank at “Anne Frank The Exhibition” at the Center for Jewish History. Photo by Getty Images

For my bat mitzvah, my parents surprised me with a stop in Amsterdam — en route home from Israel to New Jersey — to visit the Anne Frank House. It was so many years ago that I’d be lying if I claimed to remember every detail. But most salient and unforgettable was this feeling: Anne Frank stood here. She wrote her diary here, and there, and in that room. Her hands pasted the photos on this yellow wall. She was here. Now I am.

“There is this drive in us to visit pilgrimage sites,” Ruth Franklin, author of the new biography The Many Lives of Anne Frank, told me. People began showing up at the building almost as soon as the diary was published, she said, long before it became an official site. When someone we admire feels unreachable, “it’s just a natural human tendency to want to be in that person’s space in whatever way we can and share something of their experience,” Franklin said, putting into words what I felt but couldn’t possibly have articulated when I was 12. “It’s a way of feeling close to somebody when there isn’t any other way of being close to them.”

Anne never made it to her 16th birthday or to America, no matter how hard her father Otto tried to extract the family from peril and find safe haven here — where he interned at Macy’s and a bank between 1909 and 1911 — or anywhere. Instead, they hid in the heart of Nazi-occupied Amsterdam, in the secret annex that today draws more than a million visitors every year.

Now, a full-scale recreation of those famous rooms has arrived where Anne never did. “Anne Frank The Exhibition” opened at the Center for Jewish History in New York City on Monday, in conjunction with International Holocaust Remembrance Day and the 80th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz. For the first time, the Anne Frank House itself — the nonprofit that runs the museum at 263 Prinsengracht — is offering visitors a chance to have an in-person annex experience outside Amsterdam.

“To have a strong engagement with the story of Anne Frank, you need to have some personal experience. You want to be immersed in the story like you’re immersed at the Anne Frank House,” executive director Ronald Leopold told me. For years, his team has been discussing what it could provide audiences who can’t make it to Amsterdam, who can’t navigate the site’s inaccessible spaces, or who might miss out on fast-selling tickets. They’ve launched virtual tours, for example, “but at the end of the day, you still look at the screen.”

“We feel that our responsibility is huge,” Leopold said, to carry on Otto Frank’s mission of spreading Anne’s words far and wide so that young people in particular learn about history, learn from history, and take action in their own communities. This mission has felt especially critical amid “a rise in antisemitism and other forms of group hate” in recent years, including since Oct. 7, Leopold said. “It’s not just a story about the past.”

The sense of timeliness and urgency are not solely about a surge in antisemitism, Gavriel Rosenfeld, president of the Center for Jewish History, told me. “In our fraught political moment, whether we’re talking about domestic American politics or the politics of the Middle East, in a time of heightened crisis, and especially in a time of war, truth is always the first casualty, and people politicize history more readily now than in recent memory,” he said. “In a time of overheated rhetoric, we need to always go back to the historical record.”

In this case, Rosenfeld said, the exhibition goes back to the historical record to answer: Who was Anne Frank? What happened to her?

A real person

Entering the exhibition, you immediately see the Frank family’s floral dishes, one of more than 100 artifacts on view — some within the meticulous annex room recreations and some, like the crockery, in the more traditional museum displays surrounding them. Franklin, who spent several years researching Anne’s life and legacy for her book, was struck by the place settings. “It gives you the sense of what a normal family they must’ve been,” she said.

The exhibition builds gradually, starting in bright rooms depicting the Franks’ lives in Germany in the 1920s and in their new home in Amsterdam, where Anne and her sister Margot thrived even as danger loomed. There are happy snapshots of the family and Anne with her friends, and the only known film footage of the curious, buoyant diarist-to-be, peering out a window to see a bride and groom.

The walls get darker and the lights dimmer. Hitler comes to power in Germany and, eventually, the Netherlands fall under Nazi occupation. In one particularly grim room, I stood surrounded on three sides by screens showing the German invasion and the ensuing laws, actions, and brutality against Jews. The volume felt deafening and the large room suddenly suffocating.

A glow emanates from the bookcase propped open in the corner. Past the iconic threshold are those yellow walls again — not the real ones but fastidiously recreated. The rooms are tidy, but cramped and musty, with blackout screens at the ready. First Otto, Edith, and Margot’s room, followed by Anne and Fritz Pfeffer’s and the windowless washroom they all shared. The illusion is disrupted by another black museum hallway that leads to recreations of Hermann and Auguste van Pels’ room, which doubled as the kitchen and common space, flanked by Peter van Pels’ tiny bedroom.

As you pass through, overlapping recordings tell you about where you are, the sounds mingling from rooms so close together — just as the residents’ voices must have as they talked, joked, and quarreled in such tight, almost claustrophobic quarters. When they were allowed to make any noise that is.

For 761 days, the rooms of the annex at the back of 263 Prinsengracht were full — not only of stuff, but also of life, frustration, hope, and constant fear. One wrong move — an open window, a heavy tread, an attentive neighbor — and it might all be over, as it eventually was. Today, those rooms in Amsterdam are often full of visitors, but also profoundly empty. No furniture or any things in situ. Just empty space and your imagination.

“To know that that’s where all of those scenes and detail in the diary took place, and they’re gone now, all of it’s gone — that has a unique power in that authentic space,” said Doyle Stevick, the executive director of the Anne Frank Center at the University of South Carolina and the educational advisor for the New York exhibition.

It’s striking, then, to see the recreated rooms crowded with objects. Beds, chairs, tables, rugs, blankets, shoes, glasses, backpacks, games, books, papers, pencils, scissors, radio, pots, and more. A few are real artifacts, others are replicas. “This emptiness in Amsterdam is very telling,” Leopold said. But thousands of miles away, “in order to achieve the same kind of emotion, you have to do it differently.”

In recent decades in particular, Anne has “become more of an icon than a real person,” Franklin said, which “leads people to extrapolate from her words whatever they want.” By reconstructing her living space, the exhibition serves as an important reminder to visitors, she said. “I hope it just brings them back to the existence of Anne Frank as a real person.” And she hopes the exhibition can restore an understanding of Anne’s diary not only as a universal message promoting peace and tolerance, but also as a document warning against the specific dangers of antisemitism.

You emerge on the other side of the annex recreations to learn the fates of its residents and millions of their fellow Jews across Europe, walking atop an annotated map encased beneath the floor and surrounded by panels on camps and killing squads. This is the reality Anne found herself in upon her arrest on August 4, 1944, three days after her final diary entry.

A photo from the first stretch of the exhibition is projected again on one wall. It’s Anne’s kindergarten class, roughly half Jewish. One by one, 10 of the 15 Jewish children vanish into faceless black shapes as a voiceover narrates a name, age, and place of death.

“Annelies Marie Frank. 15 years old. Bergen Belsen.”

An on-ramp

Fourteen years after my bat mitzvah visit to the annex, I joined the journalism cohort of FASPE (Fellowships at Auschwitz for the Study of Professional Ethics) on a two-week trip to Germany and Poland. One of the founding principles of the nonprofit, where I now sit on the board, is that the fellowship must take place in Europe to capitalize on the power of place. We walked through the fields in Auschwitz, gathered around tables at Wannsee, and crouched down to read Stolpersteine in Berlin.

Visiting a historical site is, in a way, “the closest thing we have to a time machine,” Eric Muller, who was on the faculty for the law cohort and serves as FASPE’s academic director, told me. “There’s something about the past that sticks to a specific site,” he said, like an emotional echo that never entirely fades. “It has the power to jolt you” into a different emotional state more open to connecting with the past. The power of place, he said, is like encountering a “wormhole in time that I desperately wish I could crawl all the way through.”

Intriguing as the announcement of an annex replica was to the grown-up version of a 12-year-old history nerd — who could imagine no greater gift than a visit to the Anne Frank House — both she and the FASPE alum in me were hesitant. I could guess that a recreation wouldn’t conjure the precise alchemy I’d felt in Amsterdam all those years ago. Because, of course, Anne didn’t literally stand there.

“When we are with something that itself was in the past, it doesn’t just represent the past. It doesn’t just copy it. But it endured it, and it lasted into our time,” Carolyn Korsmeyer, author of Things: In Touch with the Past, told me. . When we step into a building or a ruin with some understanding of what once transpired in that physical space, she explained, it can be a riveting and affecting experience. “Being in the presence of the real thing has an impact that the replica references, but doesn’t provide itself. Which doesn’t mean it’s without value,” she emphasized. “A replica of a space, if it is to scale, is quite vivid.”

I didn’t anticipate just how compelling this one would be. If Amsterdam gave me that intangible but visceral echo, New York transported me into the minutiae and anxiety of everyday life in the annex, allowing me to take in the colors and textures and quotidian clutter of this precarious bubble of safety that ultimately popped with the most dire consequences.

It’s abundantly clear that nobody intends for the exhibition to replace the Anne Frank House. “No one would in their right mind would claim that someone visiting the exhibit at the Center for Jewish History is visiting Anne Frank’s house,” Rosenfeld said. “It’s not the house. It’s an ersatz reproduction,” he said. “But it still can serve a very important pedagogical function.” And while purists might call it flawed for being inauthentic, he added, “the gain that is to be had by introducing people to something simulating the cramped quarters of living in hiding, always fearful of the Gestapo knocking on the door — that is powerful.”

What it also does, Rosenfeld said, is personalize the story of the Holocaust. It provides what Stevick, who worked on designing the associated curriculum for students, calls an “on-ramp,” or an entry point. “We start with Anne Frank and make sure that she is a story of the Holocaust, not the story of the Holocaust,” Stevick said. Both he and Leopold will be watching closely, collecting survey responses, and listening to feedback to see how students, teachers, and the general public respond to this first-of-its-kind experience outside of Amsterdam.

None of us, to state the obvious, will ever be Anne Frank hiding in the annex from 1942 to 1944. In the absence of a time machine or a wormhole that would allow us to close every spatial, temporal, and experiential gap, we resort to the next best things, searching for the nearest approximations. If traveling to the annex in Amsterdam gets us as close as we might ever be, then visiting the exhibition in New York City gets at least part of the way there.

I can easily imagine some of the thousands of schoolchildren already slated for tours becoming, in their wake, just as fascinated with Anne as I was at their age — and for that “on-ramp” to foster a deeper interest in history and what it can tell us. They might read and reread Anne’s diary, see a play or a movie, listen to a podcast, or tour her space in virtual reality.

And maybe five or 10 or 15 years down the line, they’ll stop in Amsterdam to stand where she did, all because one day they took a class trip to stand where she didn’t.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO