The Binding of Isaac, the pardoning of Hunter Biden

Like Abraham, the biblical patriarch, the president was torn between faith (in the system) and family

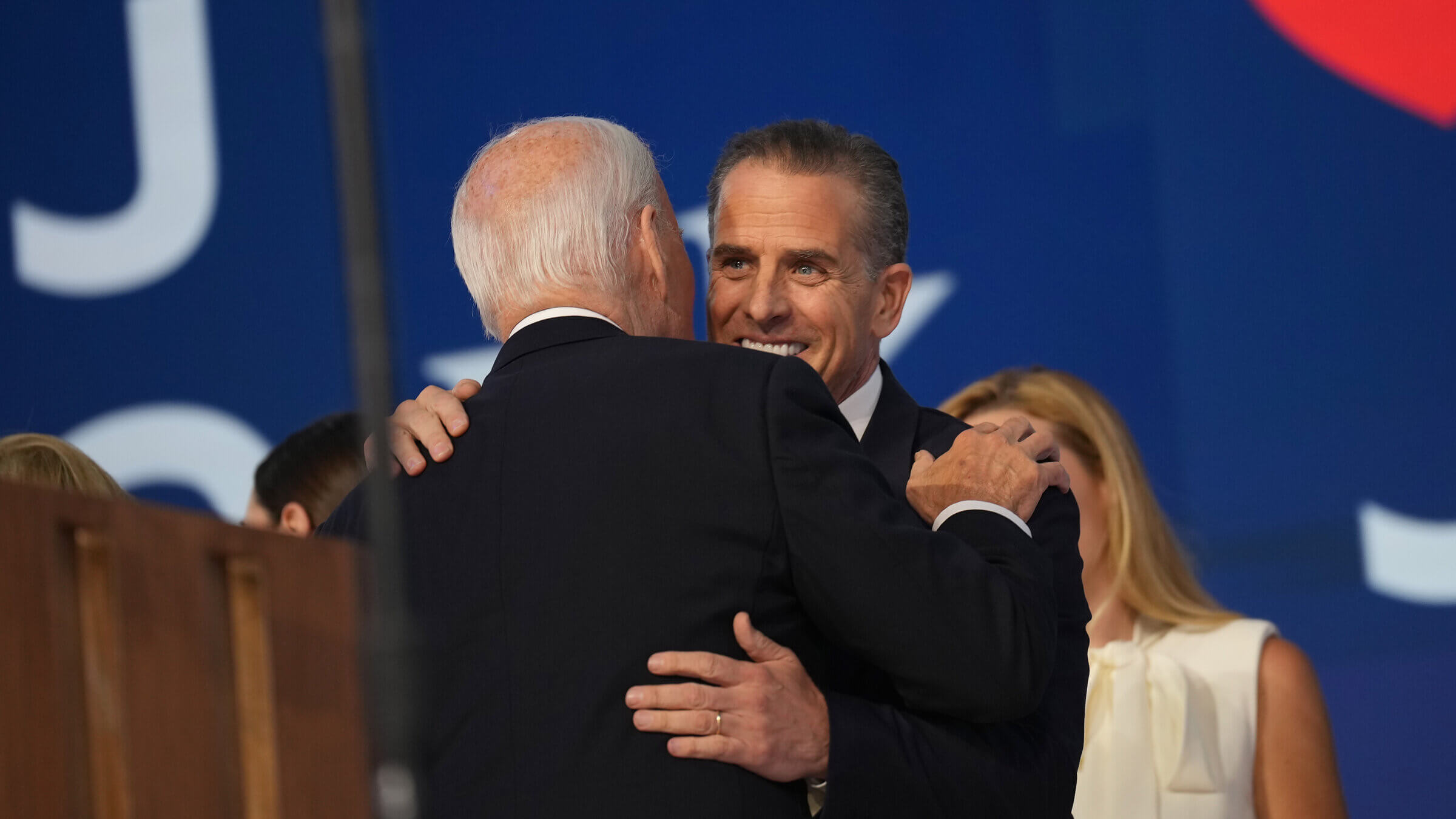

President Biden embraces his son, Hunter, earlier this fall. Courtesy of Getty Images

Judaism, Christianity and Islam are called Abrahamic faiths not only because Abraham was the first monotheist but because he was so famously devoted to God. His obedience was so strong that he was willing to slaughter his son Isaac as an offering to God — and might have, if an angel hadn’t stopped him.

President Joe Biden, an observant Catholic, in some ways faced a similar choice with his son Hunter, who was convicted of tax evasion and lying on an application for a gun license. Would Biden sacrifice his son, allowing him to be sentenced to up to 25 years in prison, out of devotion — not to God but to the American justice system?

The president has long positioned himself as an advocate of law and order and a loyal public servant. He had promised numerous times not to pardon Hunter, who had long ago repaid his debt to the government, and to accept the results of the trial.

But he broke that vow on Sunday, issuing an unconditional pardon of Hunter in the waning days of his presidency. With this pardon, he echoes former President Bill Clinton’s late-term pardon of his brother, Roger, and — ironically — aligns himself with his nemesis, President-elect Donald Trump, in terms of assessing the Justice Department prosecution as having been politicized.

The pardon, of course, is not just laden with political and legal weight; it’s also a tortured family drama, one that played out on a very public stage. Like Abraham the patriarch, Biden’s commitment as a public servant to protecting the rule of law was directly juxtaposed with his commitment as a father to protect his family.

In the Binding of Isaac, Abraham has the knife to Isaac’s throat when an angel intervenes, sending a ram to be slaughtered instead. But he is seemingly lauded for his willingness to go through with the act, his devotion to God taking precedence over any other commitment, even one as sacred as that to a child.

“Because you have done this and have not withheld your son, your favored one, I will bestow My blessing upon you,” the angel says on God’s behalf (Genesis 22:16). “All the nations of the earth shall bless themselves by your descendants, because you have obeyed My command.”

This story is often read as a positive example; given the ultimate test, Abraham passes by remaining steadfast in his obedience, willing to make any sacrifice on behalf of God. And reading it like this, it seems as though Biden, a religious man, should have put his devotion to a higher power — in this case, the presidency and the law — over his child.

But the rabbinic sages do not all agree that Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice his son is to be admired. In fact, many think that Abraham would have done a great evil if he had gone through with it — and that God never wanted him to.

In the Midrash, the rabbis grappled over and over with how to understand something they saw as an impossible ask. One posits that swearing on the life of your child automatically invalidates any vow because carrying it out is impossible — therefore, he argues, God could never have expected Abraham to kill Isaac. Others infer that God never asked Abraham to sacrifice his son literally, because God only considers kosher animals fit for offerings, and humans are not considered kosher. They cite God’s rules against human sacrifice, and claim only a false god would ask for such a thing.

Key to these interpretations is a lesser-known story about child sacrifice. In the book of Judges, Jephthah asks God to help him win a battle, and vows to sacrifice the first thing he sees upon returning home. He wins, defeating the Ammonites, but the first thing he sees is his daughter, his only child. Jephthah is horrified; he cannot break a vow to God. He gives his child two months to find a loophole, but she eventually returns to be sacrificed.

Jephthah is not lauded like Abraham for following through and killing his daughter. The Midrash claims that God sent Jephthah’s daughter to greet him because he took a vow carelessly and needed to be taught a lesson. But even though it was God who sent the daughter as punishment, the rabbis say that Jephthah was punished a second time for fulfilling his vow and sacrificing her; if Jephthah was a true man of the Torah, he would have known that God does not want a child sacrifice.

In the interpretations of the Binding of Isaac, the rabbis refer back to Jephthah — even though that incident happened well after Abraham’s death. Jephthah’s punishment for killing his daughter, they say, is proof that God never wanted Abraham to literally kill his son. There’s no one, not even God, who could ask for such a thing.

Throughout all of the specific intertextual somersaults the rabbis perform in the Midrash, the clear throughline is their inability to condone a parent sacrificing a child, no matter how high the power they’re serving or how lauded their reasons.

Biden, of course, was never considering killing Hunter. But the idea that no higher power can come between parent and child, it seems, still held true.

Even though the president had vowed not to pardon Hunter, and to accept the judgment of the courts, he ultimately decided that if it was within his power to help his son, he would do it. Perhaps the real sin in the eyes of the rabbis would have been Biden putting himself — his political power, or his legacy — before his son.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO