How Quincy Jones scored with the gritty story of a Harlem Holocaust survivor

Jones’ 1964 score for ‘The Pawnbroker’ became an instant classic

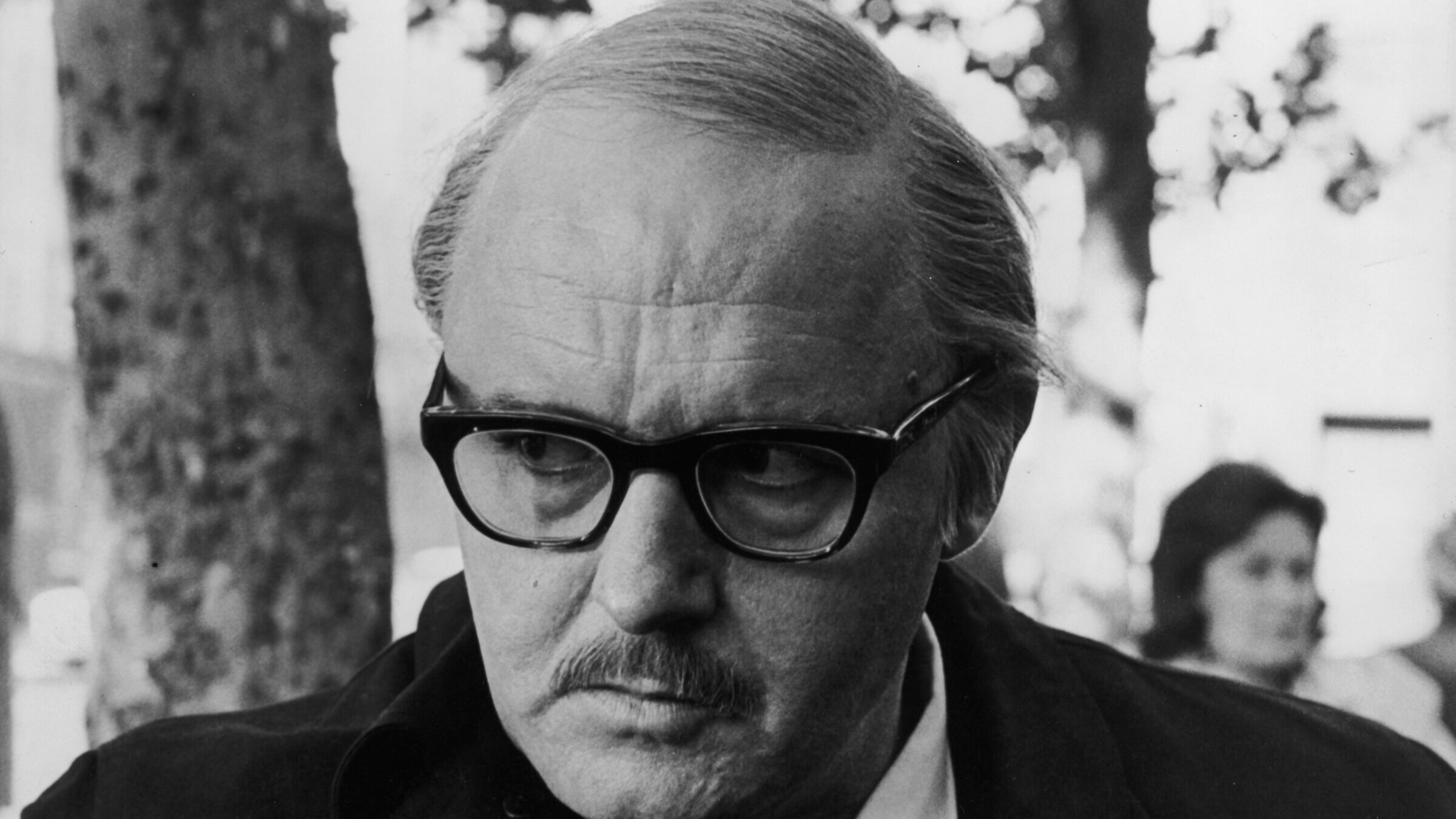

Rod Steiger starred in The Pawnbroker. Photo by Getty Images

The composer and arranger Quincy Jones, who died Nov. 3 at age 91, was a pioneer in many respects. His first film score assignment was 1964’s The Pawnbroker, which was the first US movie that discussed the Holocaust from the viewpoint of a survivor.

Based on a 1961 novel by the American Jewish author Edward Lewis Wallant (who also wrote The Tenants of Moonbloom) the movie was directed with trademark grit and New York flavor by Sidney Lumet, who had his stage debut at the Yiddish Art Theatre at age five.

Set in Harlem, where Sol Nazerman, a mournful Holocaust survivor, encounters a series of impoverished slum dwellers, the variegated cast of characters inspired an appropriately diverse sound landscape from Jones. Critic Vladimir Bogdanov praised the composer’s astute mélange of jazz, bossa nova, soul and vocals by the sublime Sarah Vaughan on the soundtrack album that made an intense narrative all the more galvanic.

Although Quincy Jones managed to outdo himself just a couple of years later with the stunning film score to In the Heat of the Night, The Pawnbroker had different, and highly specific, requirements.

The composer Jack Curtis Dubowsky has observed that the film employed small combo improvisation that provided an authenticity lacking in other onscreen jazz scores of the day. Doubtless in collaboration with Lumet, Jones decided to alternate between dramatic moments when no music was heard, to raising the decibel level to the point of discomfort for some viewers.

Lumet is considered to have borrowed from French New Wave directors the flash cut, or extremely brief shot, sometimes as short as one frame, which is nearly subliminal in effect, to evoke the Jewish historical past. In such flash cuts, Jones subtly offered music in different orchestrations, from a mellifluous pre-Holocaust gathering of strings, flute, woodwinds and harpsichord, to a more percussive and discordant keyboard for contemporary images.

In Jones’ seemingly endless inventiveness, sometimes even concrete music is heard, using recorded noises as raw material. When Nazerman hears dogs barking in the street, a flash cut of dogs chasing a Jewish concentration camp intrudes on his consciousness. As this was Jones’ first full-length screen score, he may have been especially collaborative in spirit about when to omit music, as in flashback scenes of concentration camps.

In the film’s final scene (spoiler alert!), when Nazerman impales his hand on a pawn ticket spike, jazz trumpets blare in a crescendo to replace any human scream. The precise meaning of this juxtaposition of African American jazz with mute Jewish suffering depended on the spectator.

A reviewer for Film Quarterly kvetched that Jones’ amped-up volume at the end of The Pawnbroker was an example of “deliberately created incidental music loud enough to be physiologically disturbing.” In other words, to communicate a character’s pain, unease was inflicted on cinemagoers.

By contrast, Lumet explained the loud, frenzied sounds in an interview for Films and Filming in October 1964, before The Pawnbroker was released. He claimed that the forcefulness of the sonic jazz apotheosis was a mutual decision between Jones and himself “to avoid sentimentality” at this part of the story. The music’s vivacity was intended to counteract the grievous images onscreen as a form of rebirth experienced by Nazerman.

Given the uniformly tragic content of the film, some reviewers were dubious about whether this idea of renaissance for the suffering Nazerman was plausibly conveyed in the film itself, whatever Lumet and Jones’ intent may have been.

The film historian Annette Insdorf was apparently among those convinced by Lumet’s argument. Insdorf posited that Jones’s jazz score replaced the “mute scream” of the Holocaust survivor, who has witnessed events “so devastating” that they cannot be recounted. Nazerman’s silence, according to Insdorf, is also an expression of “essential isolation,” insofar as any scream by him would go unheard anyway.

The persistent ambiguity of such scenes might have been accentuated by the blunt, in-your-face effectiveness of Jones’ aural imaginings. His sounds reinforced expectations for characters, just as the film itself was criticized by some 1960s viewers for fulfilling stereotypes of Jews as pawnbrokers in ghetto neighborhoods and members of minority groups as criminals.

Yet Jones’ music was redeemed, even if Nazerman ultimately was not, by the musician’s ever-questing intelligence and curiosity about unfamiliar sounds. Soul Bossa Nova, which became a popular instrumental, was included in Jones’ score. It featured the cuíca, a Brazilian instrument that makes a derisive laughter-like noise, adding irony to the protagonists’ travails.

Rather than paradoxical emotionalism, Lumet might have had a different result had he hired his initial choice of soundtrack composer: John Lewis, leader of the Modern Jazz Quartet. Ralph Rosenblum, the film’s editor, complained that Lewis’ music was “too cerebral” and suggested Jones instead. So instead of spare, intellectually purist jazz tones, a more popular and populist glamor was epitomized by the luscious, triumphant singing of Sarah Vaughan in a more conventional ballad by Jones on the film’s soundtrack album.

Dramaturgically, Jones captured a visceral, showbizzy energy that was entirely appropriate, especially for tawdry nightclub scenes. In this way, Jones’ full-hearted music matched the extroverted intensity of the bravura performance by Rod Steiger in the title role.

Steiger was not Jewish, and his middle linebacker’s physique and fleshy face did not permit him to convincingly express any corporeal vulnerability or suggest the famine and dysentery that were inflicted on prisoners in concentration camps.

Quincy Jones might have been differently challenged by this assignment had a septuagenarian Groucho Marx been granted his repeatedly expressed wish to play the role of Sol Nazerman onscreen. Perhaps if the physically frail Groucho had been onscreen, the disembodied jazz thoughts of John Lewis would have been a more apt accompaniment. Yet so multifaceted was Quincy Jones’ talent that in all likelihood he would have been able to create appropriate sounds to evoke the pensive side of Julius Marx and avoid the grotesqueness that repeatedly results when movie clowns, from Jerry Lewis to Roberto Benigni, tackle the theme of the Holocaust.

With comparable deftness, The Pawnbroker has weathered some influential nay-sayers over the years. Film maven Jonathan Rosenbaum is one of these, decrying The Pawnbroker as an “ambitious but pretentious adaptation” marred by Lumet’s “clumsy appropriations” of French New Wave approaches to editing and flashbacks that “only increase the stridency of the material.”

Even more vehemently, the film history professor Ilan Avisar has denounced The Pawnbroker as an “extreme example of Jewish self-hatred” and slated the film for its supposed “bogus analogy between the horrors of the Holocaust and living conditions in Spanish Harlem.”

Back in 1964, in Films and Filming Sidney Lumet had already tried to forestall such complaints by assuring moviegoers that his filmmaking team had no intention to “show Harlem as a modern concentration camp.” On the contrary, the liveliness of Harlem, despite evident anguish, was a major theme of Lumet’s creation. And this vitality and élan was unforgettably captured with zest by the already much-missed and irreplaceable Quincy Jones.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO