Would you put jalapeños in matzo ball soup? This Mexican Jewish cookbook says, ‘sí’

New ‘Sabor Judio’ cookbook delivers recipes with New World flavors and Old World traditions

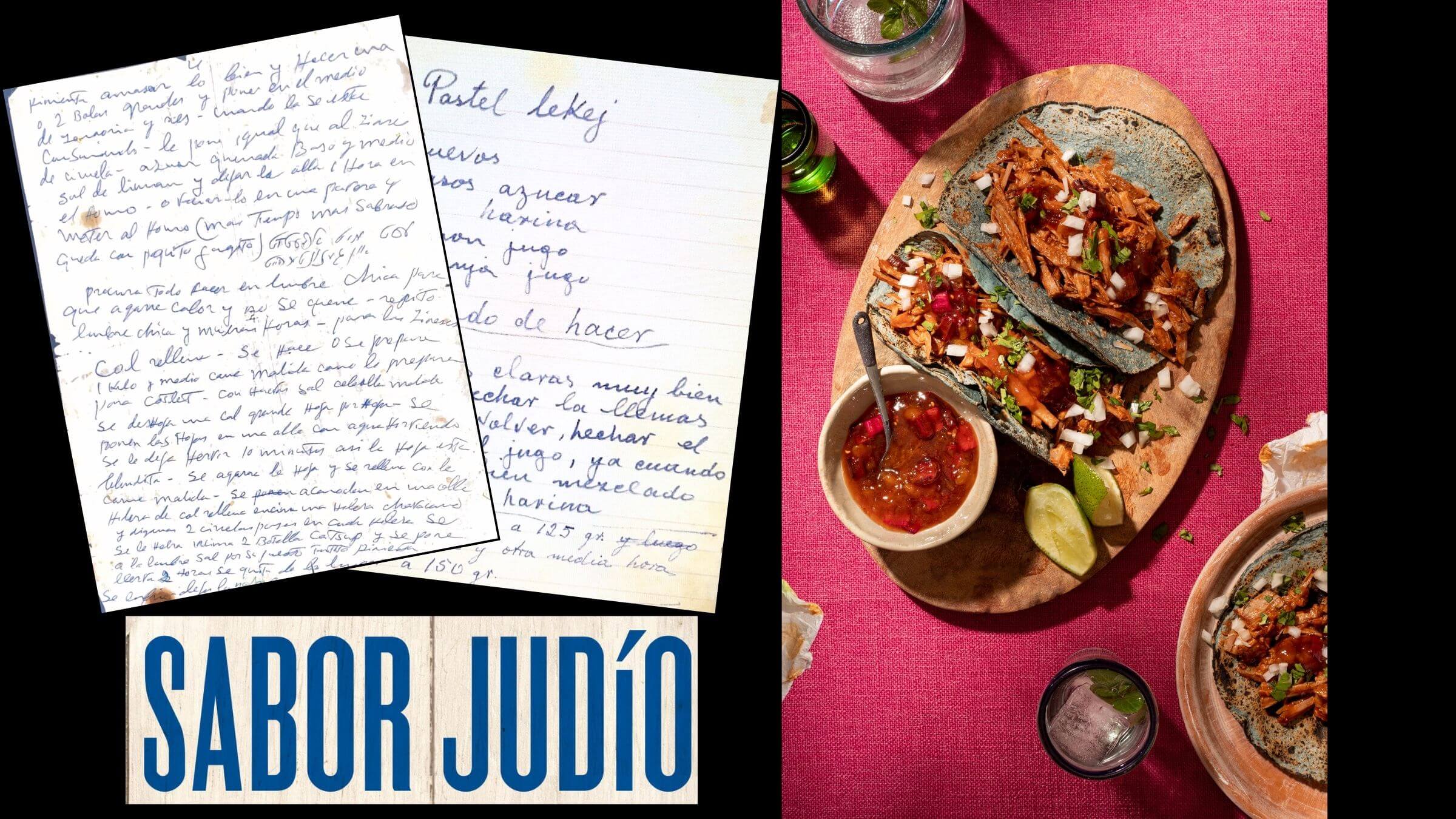

Left, handwritten recipes; right, brisket tacos from Sabor Judío: The Jewish Mexican Cookbook. Courtesy of Ilan Stavans and Margaret Boyle (recipes); Ilan Rabchinskey (tacos); University of North Carolina Press (book title)

Page through Sabor Judío: The Jewish Mexican Cookbook, and you’ll either be salivating or slightly stunned (or maybe both), depending on your palate and how you feel about messing with tradition.

Mediterranean couscous with chipotle salsa, plantain chile kugel and gefilte fish in red salsa are among the recipes offered by co-authors Ilan Stavans and Margaret E. Boyle. Stavans, an Amherst College professor, was born and raised in Mexico City’s Jewish community. Boyle, a Bowdoin College professor, grew up in Los Angeles in a Mexican Jewish family.

Now, if you’re a purist with a sensitive stomach — like my mother-in-law of blessed memory, who couldn’t bear mustard, mayo or even spaghetti sauce, never mind jalapeño peppers — Sabor Judío might not be for you. But if you’re an adventurous eater, these recipes will get you rethinking holiday menus as well as what you’re making for dinner tonight.

After all, fusion cuisine is really a Jewish tradition: We’ve been adapting our diets to local ingredients in diaspora for centuries.

Certainly the book will get you dreaming of a Passover week where you won’t dread another day of matzos, thanks to recipes for matzo chilaquiles and matzo ball soup with jalapeños. Sure, you love traditional latkes with applesauce and can even go for vegan zucchini latkes, but consider one of Stevens’ favorite dishes: latkes with mole sauce.

I daresay even my mother-in-law — who had a sweet tooth despite an aversion to strong flavors and unfamiliar ingredients — would have liked Sabor Judío’s cinnamon churro babka or challah French toast with caramel sauce.

The Mexican Jewish community

Mexico’s Jewish community is relatively small: 60,000 people in a country of 130 million. The first Jews arrived 500 years ago with Spanish conquistadors, but most Mexican Jews today are descended from immigrants who came in the early 20th century — Ashkenazim from Eastern Europe and Sephardim from Syria, Spain, Italy, Turkey and Bulgaria. Another 2,000 fleeing Hitler arrived in the 1930s and ’40s; Israelis showed up in the 1970s

“It’s easy to get people excited about the food if you’re a foodie,” Boyle said in a phone interview, “but I also love to talk about the histories of immigration that are in the book, and about diaspora and identity, and what it means to connect to your culture through food and language.”

The book took seven years to complete, from the authors’ first conversations to its publication this fall. But the timing “does feel bashert,” Stavans said, using the Yiddish word for “fateful,” given this year’s election of Claudia Sheinbaum, a Jewish woman, as Mexico’s president.

Brisket tacos and lime macaroons

Among the book’s many intriguing dishes are pan dulce (pastries) baked in shapes like menorahs and Torah scrolls; cumin rose kibbe; baba ganoush with chile; snapper ceviche with maror (bitter herbs from the Seder); chicken liver with tortilla chips; ice pops made with Manischewitz wine, and mango noodle kugel.

Boyle’s favorite recipes include lime macaroons with toasted coconut, which are fragrant and easy to make, along with brisket tacos. The brisket meat is marinated in salsa from three types of chiles and the tacos are topped with her grandmother Phyllis’ rhubarb sauce, “so you have that balance between the sweet and spicy.”

Stavans said latkes with mole sauce are “a staple in my family,” but he also adores caldo verde, a green chicken soup with matzo balls and corn. A recipe for rice pudding with cinnamon and lemon takes him back to his childhood.

As for the spiciest recipe, Stavans said it’s probably stuffed poblanos with guacamole and grivenes, which are bits of fried chicken skin sometimes referred to as “Jewish bacon.”

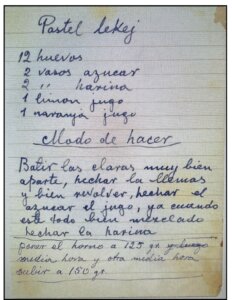

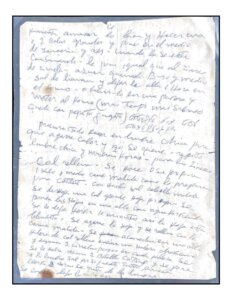

Recipes handed down through generations

Boyle’s contributions include recipes from her great-grandmother, Malka Poplawski, who emigrated to Mexico City in the 1920s to escape pogroms in Poland. Many of Stavans’ offerings come from his late mother, who had Alzheimer’s but “managed, literally at the very last minutes of her conscious life, to send me a PDF with the recipe book that had belonged to her mother,” an immigrant from Eastern Europe. Written in Yiddish, Polish and Spanish, the recipes include handwritten notes from the women who used them, crossing things out and even making jokes and drawings to express ridicule: “Oh, really, you put that much sugar?”

Thanks to an article in Diario Judio, a Mexican Jewish newspaper, the book also includes recipes from other families. And since so many of them have instructions like, “Add a little lemon or a little sugar,” the authors brought in Jewish cookbook author Leah Koenig to test and standardize everything.

The immigrant’s anxiety

Those handwritten annotations allowing for preferences of taste and substitutions also speak to “the question of how does Jewish food become Jewish?” Stavans said. “One of the beauties of the recipe books that Margaret and I both have is that you can see the anxiety of the immigrant saying, ‘I want to continue cooking gefilte fish or latkes,’ but the ingredients are no longer there.”

So the book reflects not only how Jews adapted traditional recipes, but also, he said, “what Mexican Jews learned to eat” in their new environment: tropical fruits and juices, tomatillos and avocados, cilantro and hot peppers, tortillas and quesadillas.

And while Jewish immigrants of bygone eras had no choice but to replace old-country ingredients with whatever was in neighborhood markets, Boyle noted that they were ahead of their time, anticipating the contemporary obsession with locally sourced ingredients.

The book also encourages home cooks to “experiment, to play with the recipes and make all the modifications they need,” Boyle said, just like the recipes’ original chefs did. For example, instructions for sopa de tortilla, a soup typically made with chicken broth and cotija cheese, notes that the cheese may be omitted to make the dish kosher, while vegetable broth can be subbed for chicken broth to make it vegetarian.

Any guidance for folks more accustomed to blintzes and chicken soup than cilantro and chipotle?

Just go for it, advised Stavans. “This is more than a cookbook,” he said. “It’s a manual on how to live life and love life by taking risks. The more courageous you go, the more colorful life is going to be. I think one of the features of Mexican Jewish life is that color and variety of tastes.”

RECIPE FOR LIME MACAROONS

Makes about two dozen cookies. Preparation time: 20 minutes. Baking time: 25 minutes

INGREDIENTS

- 14 ounces unsweetened, flaked coconut

- 1 cup sweetened condensed milk

- 1 teaspoon vanilla extract

- 2 packed teaspoons grated lime zest

- 2 large egg whites

- 1/4 teaspoon kosher salt

DIRECTIONS

- Heat the oven to 325 F and line two large baking sheets with parchment paper.

- In a large bowl, mix together the coconut, condensed milk, vanilla and lime zest.

- In a stand mixer fitted with a whisk attachment (or using a handheld electric mixer), beat together the egg whites and salt until stiff peaks form. Gently fold the egg whites into the coconut mixture until no streaks remain.

- Scoop out round tablespoons of the coconut mixture and form small mounds on the baking sheets, leaving 1 inch of space around each cookie.

- Bake, rotating the baking sheets back to front and top to bottom halfway through, until gold around the edges and on top, 20-25 minutes. (The cookies will be soft but will firm up as they cool.) Remove from the oven and carefully transfer to wire racks to cool

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO