This writer has finally forgiven Glenn Close; whether Glenn Close cares is another story

Bruce Eric Kaplan’s latest tells a cautionary tale of adventures in the screen trade

Bruce Eric Kaplan, circa 2015, at the Paley Center. Photo by Getty Images

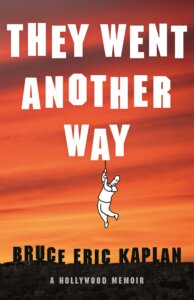

They Went Another Way

By Bruce Eric Kaplan

Henry Holt, 272 pages, $29

Bruce Eric Kaplan’s wryly comic, decidedly low-key memoir calls to mind David Yazbek’s lyrics for the song “Waiting” in the Broadway musical The Band’s Visit:

Waiting, what’s new here,

You’re waiting, I’m waiting,

’Cause that’s what we do here,

Same as we do every day,

For something, I don’t know,

To happen….

A New Yorker cartoonist and a writer for such television classics as Seinfeld, Six Feet Under and Girls, Kaplan does at least have a discernible goal. He is hoping finally to get a series of his own greenlit by a network or streaming service. They Went Another Way – a title that telegraphs the outcome — shows how desperately inefficient and frustrating that process can be. Any writer dependent on gig work and responses from inundated or oblivious editors will certainly feel Kaplan’s pain.

The drip-drip-drip of Kaplan’s waiting is expressed in daily journal entries running from January to July 2022. Two afterwords update the story. The short takes make the memoir easy to read and involves readers in Kaplan’s purgatorial ordeal. But the lack of progress he encounters inevitably makes the memoir itself seem static; the reader, too, is waiting for something to happen. And, in the end, beyond some mild satire of both Hollywood stars and their entourages, the book’s narrative payoff is slight.

For all his writing credits, Kaplan’s track record as a showrunner appears to be nonexistent. But as a veteran of numerous failed pitches, he knows how the system works. With a pilot script in hand, he focuses on selling a series with a premise derivative of the 1971 film Harold and Maude, a black comedy about an intergenerational love affair. The Tony Award-winning actress Glenn Close, alternately helpful and critical, is on board to play the older woman. Saturday Night Live alumnus Pete Davidson, Close’s choice, seems poised to portray her much younger love interest – if only he weren’t so elusive and overcommitted.

Before the pilot script can go out to buyers, Kaplan must endure a seemingly endless roundelay of emails, texts and Zoom calls involving actors, producers, agents and managers. Kaplan is mostly available, desperately so; he hasn’t had a job, or any income, for a year. But coordinating with the other players is a challenge, and meetings keep getting shifted or cancelled.

When, after many delays, the script is submitted to HBO Max (now Max), Netflix, Showtime and other venues, more complications ensue. Netflix demands a script for a second episode. Showtime wants a rewrite of the pilot, too. And, at one meeting, Close suddenly pitches “an entirely different show that was about her and Pete working together at a Target in Staten Island, then traveling around the middle of the country having ‘kooky’ adventures with people.”

In his journal, Kaplan writes sardonically: “I think her hope was I would say great and throw out my entire script. Maybe I would be allowed to keep the characters’ names.” At the meeting, he says only: “It’s a lot to digest…I’m just going to absorb it.” But, for him, the relationship has been poisoned.

Fortunately, or perhaps not, Kaplan has a number of other irons in the proverbial fire. The most concrete are a potential Gilligan’s Island remake, a prospect that unaccountably excites him, and a writing gig on a show, Life & Beth, that he keeps resisting.

Meanwhile, he functions as a house husband, a pursuit that requires a different kind of patience. (His wife, Kate, also works in the industry, and they have a teenage son and daughter.) At home, Kaplan engages in a parallel waiting game, for the resolution of a heating problem. Repairmen keep showing up without the requisite tools, parts or savvy to get the job done.

When he’s not pitching or dealing with home repairs, Kaplan spends his time disposing of dead birds who have crashed into his windows, cooking complicated vegan recipes and driving his daughter to volleyball games. In the memoir, he also voices periodic angst about the state of the country and the world without adding anything substantial to that discussion.

To deal with stress, Kaplan explores meditation. He picks up his pen once again to draw cartoons. And he prepares to relocate from Los Angeles to New York. Contemplating his family, he concludes, “I have everything I need and there is nothing else that I want.” He references the philosophy of The Wizard of Oz, the profound homily that “there’s no place like home.” He even decides to forgive Glenn Close, who has long since moved on.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO