When Robert Moses laid waste to the Jewish Bronx, was he trying to obliterate his Jewish heritage?

A new exhibit about Robert Caro’s ‘The Power Broker’ sheds new light on New York’s great creator and destroyer

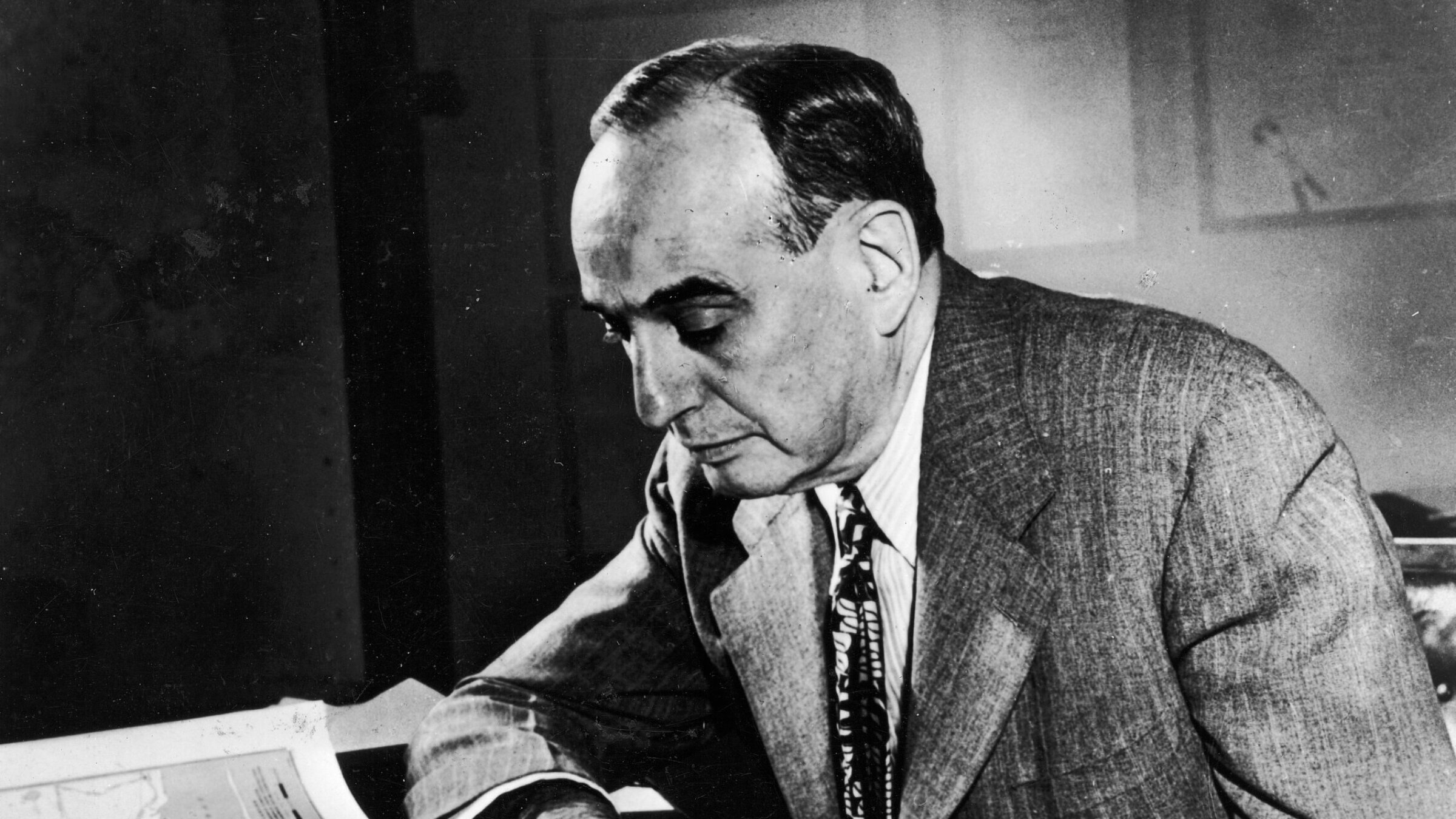

Robert Moses works with a map at his desk, 1958. Photo by Getty Images

“I FINISHED THE POWER BROKER” proclaims a coffee mug celebrating the 50th anniversary of the publication of author Robert Caro’s epic exposé of the 40-year reign of Robert Moses, the Pharaoh-like master builder of 20th-century New York.

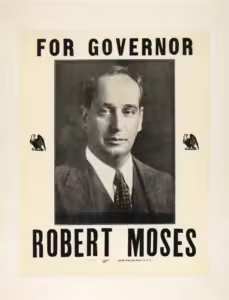

Caro won the Pulitzer Prize, among many other accolades, for his 1,344-page volume chronicling the life and times of the once idealistic urban planner who, though never elected to public office, became an indomitable and unyielding political force in the city and state of New York.

Now, the 88-year old Caro and his book are being honored at the New York Historical Society (NYHS) with the recently opened exhibit on its ground floor, Robert Caro’s The Power Broker at 50. The show is relatively small, presenting photos, letters, manuscript pages, interview drafts, and other materials related to the book. There’s more in the second floor’s long-term exhibit, “Turn Every Page: Inside the Robert Caro Archive,” which explores Caro’s entire career, starting from his early days as a newspaper reporter (that’s when his editor wisely advised him that journalism’s first rule was “to turn every page”).

The exhibit upstairs further highlights Caro’s current project, the multi-volume biography of Lyndon Baines Johnson, the first four of which have been published with a fifth and final volume nearly finished. But if you deign to ask, as many impatient Caro fans do about an actual publication date, heed the answer supplied by talk-show host Conan O’Brien who welcomed the author to his program by telling the audience, Dayenu! Hasn’t he produced enough biographical-historical masterpieces already?

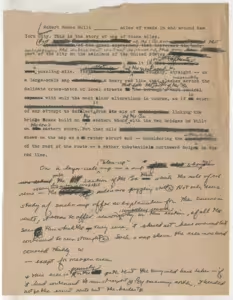

The Power Broker’s sheer length can make reading it seem daunting — hence the badge-of-honor coffee mug. And yet, as the NYHS exhibits reveal, an additional 350,000 words (enough to fill at least another volume or two) never made it into print because Caro was urged to cut them by his Knopf editor Robert Gottlieb. Those lost pages are now housed in the NHSL Caro archive. A single excised page is on display, as is Caro’s indignant letter to Gottlieb vehemently objecting to the cuts. Fortunately, Caro did ultimately agree — and the book was published, much to the ire of Moses, whose disdainful letter criticizing the author is also on display.

Rather than bemoan the absent chapters, however, I prefer to say todah rabah to the max for Caro’s extraordinary achievement. Caro’s eloquently written and utterly gripping narrative is as compelling as Tolstoy or Homer. That Caro spent a Biblical-sounding seven years of labor on the project adds to the allure of thinking of his book as a Bible about how to gain and retain political power — and a prophetic forewarning of the corruptive harm it can cause.

Most of all, what both NYHS exhibits demonstrate is how Caro plied his talents — and his doggedness —–as an investigative journalist nonpareil to turn, and then often return to, every page of his research and notes from the 522 interviews he conducted to show us how Robert Moses came to wield his massive influence: how, maneuver by calculated maneuver, Moses accrued the influence and authority to take command of virtually every construction project in New York from the1920s to the 1960s. Yes, to Moses we owe Jones Beach, Lincoln Center, and countless highways, bridges, tunnels and public parks. These projects burnished his image as a beneficent public servant — that is, until Caro exposed Moses as the ruthless autocrat he had become, and perhaps was all along.

Case in point: Few readers of The Power Broker will forget how Moses, at the height of his power, mercilessly destroyed the then mostly Jewish East Tremont section of the Bronx via mass evictions and bulldozers instead of making a minor change to his proposed route for the Cross-Bronx Expressway. Caro, who was himself born to a Jewish family in New York (his immigrant father spoke Yiddish), pointedly quotes from Fiddler on the Roof to emphasize the parallels between the eviction edicts issued by the Russian czars kicking the Jews out of Russia to the threatening demands with which Moses forced the East Tremont residents from their homes.

Having recently re-read (OK, having mostly reread) my dog-eared, heavily marked-up 1986 paperback copy of The Power Broker, I can testify to its enduring relevance to our understanding of the muddy workings of political power. The passing of the decades has also brought to the fore the environmental dangers Moses left us in the form of massive highway systems built for polluting, gas-guzzling passenger vehicles — and whose designs, by design, preempted the possibility of public transportation. Caro was prescient, even if Moses was not.

But what struck me most strongly this time around is how Caro’s book also bears witness to the life and death of generations of New York’s Jewish communities across various waves of immigration from different parts of Europe and the new lives they made in America among varying social, professional and economic classes. The East Tremont chapters, for instance, detail the hard-fought struggles of the impoverished Jews who had managed to escape the tenements of the Lower East Side for the working- and middle-class apartments of the Bronx.

“They were a long way from being rich,” Caro writes, “but the neighborhood provided its residents with things that were important to them,” such as nearby subway stops, job opportunities and shopping within walking distance, an airy public park, good public schools, and apartments that were both affordable and well-maintained. In all these ways, Caro continued, those who lived there built “security, roots, friendship, a community that provided an anchor…against the swirling, fearsome tide of the sea of life.” That is, until Moses uncaringly washed it all away.

Why didn’t Moses care? We’ll never know the reasons behind this or other of his seemingly mercurial, almost wantonly destructive decisions. But in this case, I wonder: Could it at least in part have been due to his aversion to admitting that he shared Jewish roots with so many of the people of East Tremont? Although he was born into a well-to-do German-Jewish family in New Haven, Connecticut on Dec. 18, 1888, he insisted throughout his life that he was not Jewish. He had never had a Bar Mitzvah. And why would he have? His maternal Cohen grandparents had, like his own parents, rejected Judaism and joined the Ethical Culture Society, which, ironically, had been founded by philosopher Felix Adler, the son of one of the most prominent rabbis of the Reform movement.

But despite his denials, Moses nonetheless had been labeled a “Hebrew” when he went to Yale met with antisemitic prejudice as he began his career. At the same time, those passionate denials of his Jewish heritage also led many Jewish community leaders to call him an apostate and worse. It’s unclear whether he registered on a personal level the horrors of Jews trapped in Nazi Europe, or the traumas of those who survived the death camps, or acknowledged that he owed his very existence to the fact that his Jewish ancestors had, in the mid-19th century, left behind the pervasive antisemitism of their Bavarian homes, to come to America. We’ll never know. What we do know, thanks to Caro, is that the only religion Moses ever believed in was power, and it is that blindered faith that shaped the legacy he left us.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO