‘The Day the Clown Cried’ was the film that ‘broke’ Jerry Lewis — did it have to happen that way?

A new documentary about the film sheds light on a doomed production

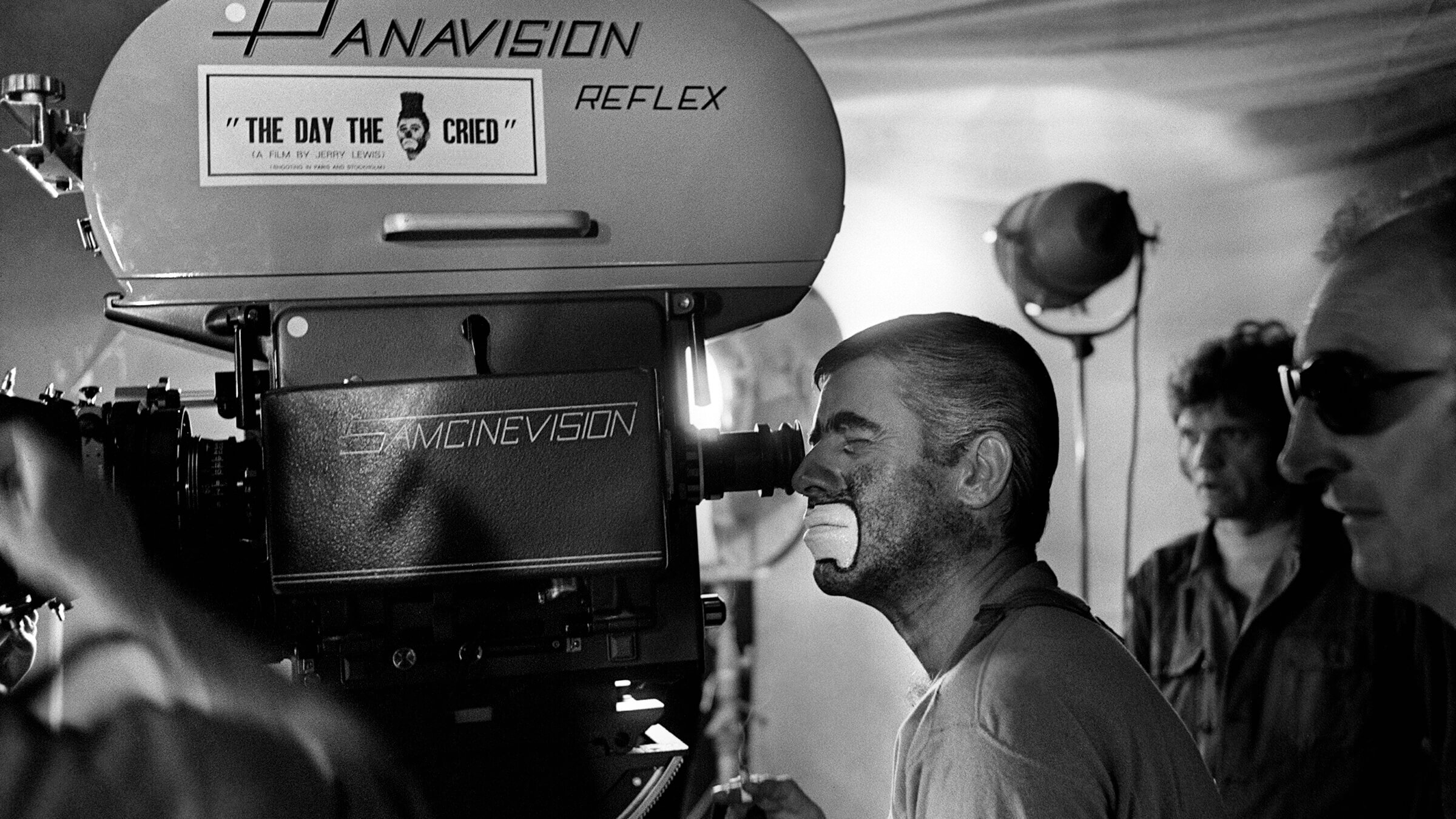

Jerry Lewis in 1972, during the shooting of the film “The Day the Clown Cried.” Photo by Getty Images

VENICE — Over 50 years after it finished shooting, Jerry Lewis’ unreleased, but hugely infamous, 1972 Holocaust film The Day the Clown Cried has been given new life in the form of a documentary about the film’s chaotic production.

From Darkness to Light, directed and produced by Eric Freidler and Michael Lurie, explores Lewis’ journey as the director and star of a dark comedy about a clown interned in Auschwitz who entertains children on the way to the gas chambers. The film was based on an original story and screenplay by author Joan O’Brien and producer Charles Denton. According to a number of celebrities interviewed for the documentary — including Martin Scorsese and Rob Reiner — The Day the Clown Cried existed in the industry for decades as a “movie myth” with much of the footage destroyed; Lewis disowned the film, and would rail at interviewers who dared to mention it.

Clown Cried had been intended to give Lewis, who played the role of Helmut the Clown, a chance to prove his talents as a serious storyteller. He did intense research to prepare for the film, and spent several weeks touring Europe and visiting concentration camps in order to make a genuinely moving film about the tragedy.

Unfortunately, everything that could go wrong did.

The production team never secured permits to film in Paris, so shooting eventually relocated to Sweden, where it was hard to find extras who spoke English or lead actors who could speak with German accents. Watching the movie clips included in the documentary, the only way to tell who the German soldiers are is by their uniforms — everybody sounds the same.

Over the course of the production, Lewis feuded with one of the lead producers, Nat Wachsberger, whose face is blurred whenever photos of him are used, making him seem almost demonic.

Eventually, in the middle of shooting, Wachsberger pulled all financial support for the film, and Lewis was forced to personally cover the expenses of paying the cast and crew, almost sending himself into financial ruin.

After Wachsbarger had already abandoned the project, it was discovered that he had never secured the rights to the screenplay. Lewis showed clips of the footage to O’Brien to convince her to give them the proper permission, but she was reportedly extremely unhappy with what had been done to her work.

From Darkness, which I saw recently at the Venice Film Festival, is not always clear about details.

Archival interviews used early in the documentary suggest that the film was primarily Lewis’ original idea and we don’t learn until much later that it was somebody else’s. The story of the production is not presented chronologically; there are jumps in time and changes in geographical settings that are not always explicitly named. At times, the film seems almost like a true crime documentary — the dark lighting of the interviewees; the tense, pulsing music; the blurring of Wachsberger’s face. Just when you think you have reached the last great insult to the production, the filmmakers hit you with another one.

But the raw footage from Clown Cried suggests the film was never able to tackle its biggest creative hurdle: making a story about the Holocaust funny.

All of the comedic clips we see feel a bit offbeat. Lewis’ forte was ’50s-era slapstick, which does not really work in a ’70s film about Auschwitz. Lewis said the film’s intense ending, in which Helmut the Clown and a group of Jewish children are in a gas chamber before the screen cuts to black, never stopped haunting him. It’s a scene that will certainly haunt viewers.

One of the most painful sections of the movie is the archival footage of Lewis continuing to promote Clown Cried, knowing he had neither the rights to release it nor plans to edit it. It is hard to watch Lewis lie on national television to interviewers like Bobby Wygant and Dick Cavett when you know that the film will not come out in“six to eight weeks” as Lewis promises Cavett on his show in 1973.

The drama in the documentary tends to feel overdone – the heavy, suspenseful techno music gets tiresome – but the story of how the failed production damaged Lewis’ psyche remains tragically compelling. Throughout the film, Lewis and his friends state that the project “broke” him.

And, despite its failures, the Clown Cried still offers current audiences much to think about in terms of the relationship between horrific events and comedy. From Darkness to Light allows the viewer to both learn about the crazy history of Lewis’ project and to gain a new perspective on laughing at tragedy.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO