Transgression, dystopia and comedy reign at a Reform synagogue in a Toronto suburb

The stories in Aaron Kreuter’s ‘Rubble Children’ seem particularly fresh and relevant after Oct. 7

Aaron Kreuter, author of ‘Rubble Children’ Courtesy of Aaron Kreuter

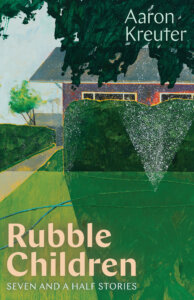

Rubble Children: Seven and a Half Stories

By Aaron Kreuter

University of Alberta Press, 232 pages, $27

The linked stories of Aaron Kreuter’s Rubble Children revolve around the community, rituals, politics and internecine battles of a fictional Reform synagogue in a Toronto suburb.

Kol B’ Seder, in Thornhill, is the embodiment of a thoroughly modern Judaism. Here Holocaust history is (mainly) a bond, and Israel (inevitably) a source of contention. By day, congregants quarrel over the prospect of a Palestinian speaker. By night, teenagers roam the temple and more forbidden precincts, exploring their burgeoning passions.

Kreuter interests himself in the most quotidian of life crises. For adolescents, that might entail an endless, exhausting hunt for intoxicants, or sudden shifts in love and loyalty that can assume tragic dimensions. For the middle-aged, it can mean relationships frayed by political disputation, or nurtured by a shared love of birdwatching.

At the core of Rubble Children is the struggle to define diasporic Jewish identity in a challenging world. Kreuter asks what it might mean to be Jewish in the shadow of the Holocaust, and without an unswerving or uncritical fidelity to Israel. Though the stories surely predate the Oct. 7 massacre and the war in Gaza, those events make them seem fresher, more relevant, even prescient.

Kreuter’s main literary vehicle is a plain-spoken realism, populated by recognizable characters engaged in familiar quarrels. But his plots sometimes levitate from the mundane, employing wildly satirical humor and dystopian flights of fancy. Each story, Kreuter explains in his acknowledgments, is an “admixture of truth, memory, imagination, improvisation, and reading.”

The funniest story — perhaps meant to be the half-story — is “‘Tel Aviv – Toronto Red Eye’: A Dialogue,” an epistolary tale that satirizes both literary publishing and Jewish politics. The premise is that the writer Stephanie Krasner has just received an acceptance from a magazine called Moose and Seal, which bills itself as “Canada’s National Magazine.” (There is, in fact, a prominent Canadian magazine, similar to Harper’s, called The Walrus.)

The note is both welcome and unexpected: Stephanie, it seems, never submitted the story to the magazine. But the editing process soon becomes “the dark and perilous journey” that one editor promises her. The dispute starts with a single political quibble. It eventually descends into a wholesale rejection of her story, which features a sexual encounter between a Palestinian-American woman and a Jewish one in an airplane washroom.

“So, you admit you’re a self-hater?” the editor writes. “We had our suspicions…We actually recommend that you change the entire plot.” The exchange reads like a writer’s fever dream, as the editor pokes ruthlessly at Stephanie’s psyche and threatens not to publish at all.

Another story, “The Krasners,” in which Stephanie plays a bit part, defies characterization. It begins with a description of the angst of adolescence, cycles through political argument, devolves into a crime story, and ends as a counterfactual history.

Kreuter’s teens experience “free-floating, general fear…, the fear of fitting in, the fear of saying the right thing, the fear of a body under revolt.” This already seems strange, or perhaps imprecise. Aren’t adolescents fearful of the opposite — not fitting in, not saying the right thing?

Reflecting on the past, the narrator recalls Kol B’Seder as a site of community where “the burn of the Holocaust was always immediately remedied with the balm of Israel.” Then he introduces the eponymous Krasners, one of the temple’s six founding families, with all the privileges that entails.

After a night of political debate (in which the narrator’s uncle takes the most adamantly anti-Israel position), a group of boys breaks into the Krasner mansion. From there, the boys’ pranks become ever more transgressive. Suddenly, we find ourselves in an improbable world, where even a massive, seemingly easy-to-detect crime goes unpunished.

Only then, with little warning and less explanation, does the “true terror” of the story begin. Tanks roll in — from where, or to what end, we never learn. The divergent consequences, we’re told, include “hideous compromise,” escape and, for the narrator, guilt so “stupendous” that “it drowns out everything else.” There’s an experimental feel to the story, whose disparate elements, while entertaining, never quite cohere.

Kreuter also plays with counterfactual history in “A Handful of Days, A Handful of Worlds.” The story centers on a lesbian couple whose relationship crumbles in a series of imagined realities. Its title is lifted from a collection by the now-quite-successful Stephanie Krasner, one of whose stories involves early Zionists colonizing Iceland instead of Palestine.

In Kreuter’s story, the date is (until the very end) always May 2, 2018. In the first world he proposes, Israel is now Israel/Palestine, and Truth and Reconciliation hearings are underway. This new state has “no hierarchy of ethnicity, no occupation, no occupying army.” In another reality, Israel instead has swerved right, passing legislation that makes every Jew in the world a citizen. In yet another, Jews and Arabs found the country together, entirely avoiding the region’s embattled history.

Tellingly, this is where Kreuter chooses to end the collection, whose title story details the adventures of a group of teenage girls obsessed with the Holocaust. They call themselves Rubble Children and take as their motto: “It happened once. It can happen again.”

The book, Kreuter writes in the acknowledgments, is “for all the children who live and who die in the rubble.” His hope, he continues, is for “a world without borders, without bombs, without rubble.” That utopian and anti-nationalist vision obviously won’t suit everyone. Kreuter has Stephanie defend it by telling a radio interviewer: “[T]his institutional fear of fiction that challenges the Jewish mainstream is exactly why such fiction needs to be written.”

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO