New Holocaust memoir shifts the focus from survivors to descendants

‘Irena’s Gift’ tries to untangle the web of inherited trauma

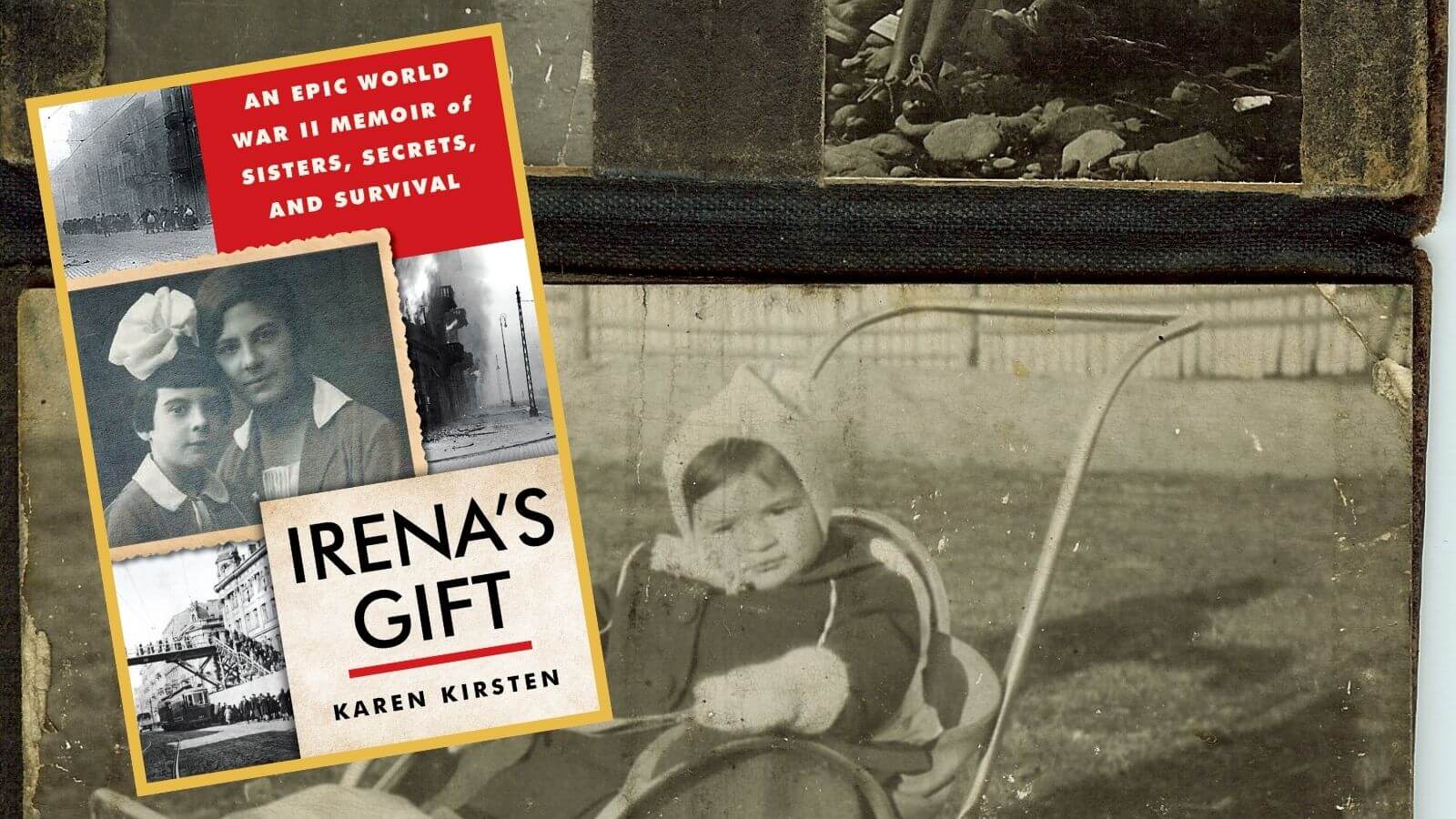

A new Holocaust memoir takes on survivors, but also their descendants. Courtesy of Kensington/Penguin

Irena’s Gift: An Epic World War II Memoir of Sisters, Secrets, and Survival

By Karen Kirsten

Citadel Press/Kensington Publishing Corp., 400 pages, $28

The flood of Holocaust memoirs continues, even if, with the passage of time, memory no longer suffices. Second- and third-generation authors must root around in archives and seek out sources much like journalists and historians. And, still, inevitably, information gaps and contradictory perspectives remain.

So it is with Karen Kirsten’s Irena’s Gift, a prickly and often harrowing account of her family, Polish Jewish (and now Australian, Canadian and American) survivors and their descendants. Scarred by persecution and war, they transmuted their ordeals into decades of buried secrets and internecine resentments.

Kirsten is frank about the epistemological challenges involved in piecing together her narrative. “Because we all remember events differently, this story changes as I tell it, depending on whose point of view I am examining,” she writes.

As is typical in Holocaust memoirs, the author-narrator braids her own quest to unearth family history with the history itself. Kirsten, who lives in Massachusetts, walks the streets of Polish towns in parallel with her relatives’ crisscrossing journeys through war-ravaged Poland, bouncing back and forth between past and present. Her clear, direct prose is easy to read. But the multiplicity of characters and story arcs can be confusing at times.

Readers must follow the sometimes intersecting, sometimes diverging stories of Kirsten’s biological grandmother, the eponymous Irena; her husband, known as Dick; Irena’s sister, Alicja, and her husband, Mietek. Irena is murdered, and Alicja and Mietek raise Kirsten’s mother, Joasia, in Australia after the war, but Joasia also has her own story – of surviving the war in a convent, and later becoming a Christian convert.

Kirsten’s relatives are brave and ingenious. They slip in and out of walled ghettos and across borders, at times shedding their Jewish identities to survive. When their luck turns, they endure prison, torture, starvation and disease. (Kirsten’s description of the torments of the Nazi-run Radom Prison, in Poland, is particularly vivid and upsetting.)

These experiences, as one might expect, don’t ever fade away entirely; the legacy of violence endures. These survivors have trouble showing, and perhaps also feeling, love. Alicja and Mietek are cold and physically abusive to their adoptive daughter. As an adult, Joasia isn’t above coming after her own children with “a coat hanger, wooden spoon or hairbrush.”. Still, Kirsten portrays her mother as mostly loving and forgiving.

The titular gift passed on by Irena is presumably her daughter’s life, purchased with jewels rescued by Dick and given by Alicja to a Ukrainian SS officer. But Kirsten’s own inheritance also includes intergenerational trauma. Much as she longs to be “the bridge between generations,” uniting her fractured family, she must also wrestle with her own emptiness and loneliness.

The book’s epigraph is a quotation from Eleanor Roosevelt that reads, in part, “You must do the thing you think you cannot do.” For Kirsten herself, that means poking and prodding at family secrets, daring to hurt in order to heal. “The thing about secrets is they are like a loose thread in a jumper; if you pull hard enough, the whole garment falls apart,” she writes. Even so, mysteries remain.

As the story begins, Kirsten paints a strange family dynamic. The woman she knows as her grandmother, Nana Alicja, treats her “like a princess.” Yet she is nasty to Kirsten’s mother, for reasons that are never entirely clear. Joasia is thrilled to discover, as an adult, that her seemingly uncaring parents are, in fact, a maternal aunt and uncle. The bolt from the blue comes in the form of a letter from Canada from Dick, her biological father, finally breaking his vow of silence.

At the book’s core is Kirsten’s inquiry into why Mietek and especially Alicja were so cruel to Joasia; why Alicja was so bitter towards her brother-in-law, Dick; and, above all, why Dick relinquished his daughter to his in-laws. Was it because he wanted Joasia to have a better life than he thought he could offer? Or was it, more simply and cold-bloodedly, because the woman he fell in love with after the war didn’t want to raise another woman’s child?

And how much does any of this matter?

We know that World War II and the Holocaust erased whole communities and families, and tore gaps through those that remained. Identities were hidden or shattered — though sometimes reclaimed. (Kirsten herself, raised Christian, ultimately reconnects to her Jewish roots.)

We also know that family stories aren’t necessarily truthful, that the truth can be ugly, and the line between right or wrong can be murky, especially in wartime. Did that Ukrainian SS officer, for all the evil acts he committed, deserve credit for saving a child, even if he had to be bribed to do it? And how harshly should we judge Alicja and Mietek, who raised their niece but harmed her in the process?

“History is not a box you tie a pretty ribbon around,” Kirsten writes. “There are no neat bows to finish things off.” Despite her meticulous research, and the accumulation of historical detail, Irena’s Gift offers only an unsatisfying uncertainty.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO