Moses needed Aaron to communicate. Biden could have used him in debate.

The president, going against Trump, had a failure to communicate

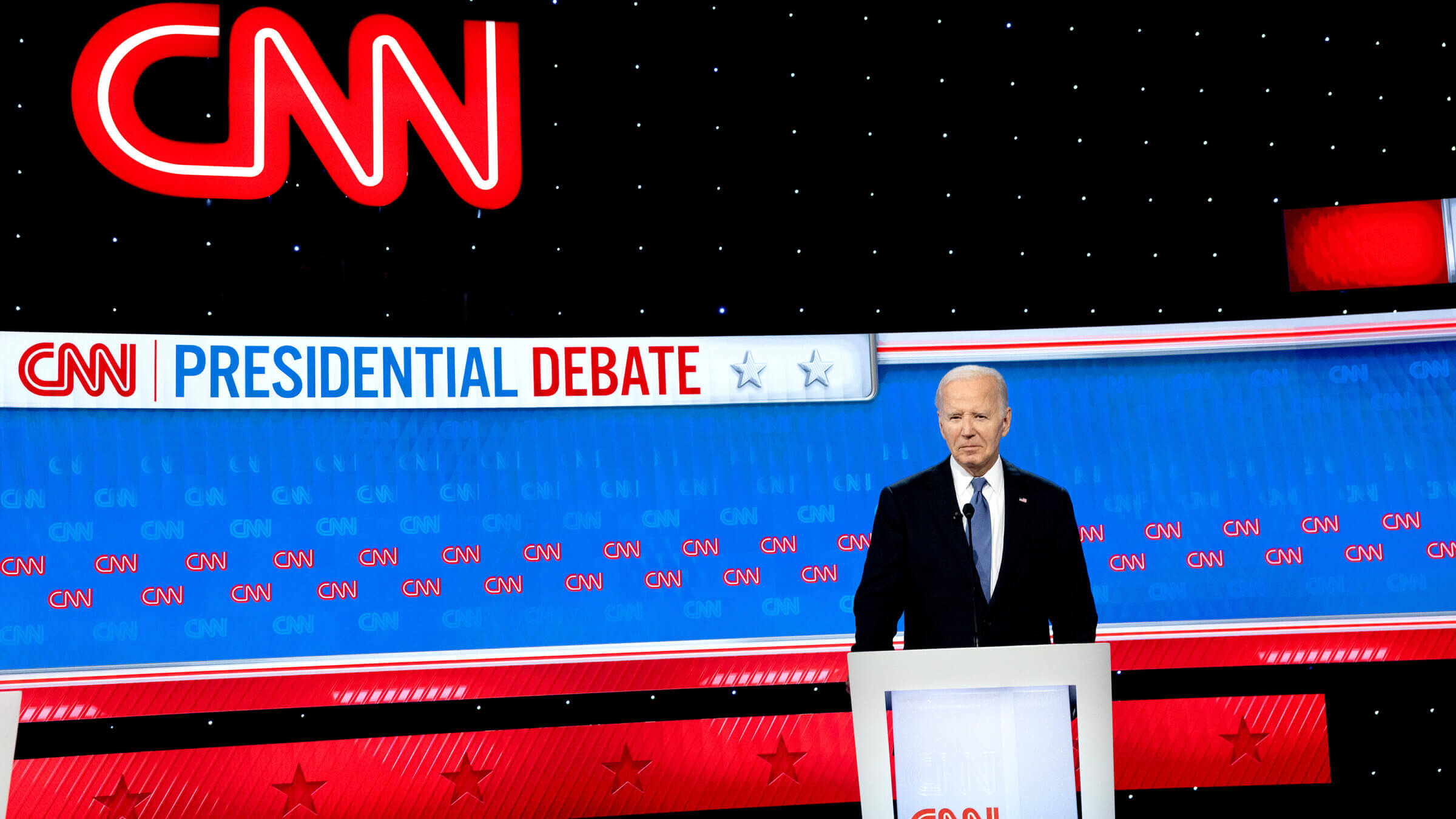

Joe Biden at the first 2024 presidential debate. Photo by Eva Marie Uzcategui/Bloomberg via Getty Images

There is a famous leader who, while humble and compassionate, struggled with a stammer.

Tasked with leading a nation, he answered that he was slow of speech. Thankfully, he had an interpreter. I speak of Moses, whose older brother, Aaron, often served the role of proxy orator.

President Joe Biden has a brother. Two, actually. Watching his wooden and at times incoherent speech in Thursday night’s debate, it was hard not to think, “This guy needs an Aaron.”

Like Moses, Biden has struggled throughout his life with stutter, but nonetheless managed to rise to the top of a profession built around public speaking. Subdued for years, Biden’s speech disorder has recently made more appearances on the campaign trail, combining with reports of a failing memory to raise concerns that he is already too old to lead the free world, let alone serve a second term that would end when he is 86.

(His opponent and predecessor, former President Donald Trump, 78, has ventured to say Biden is senile, challenged him to take a cognitive test while misremembering the name of the physician who administered his own.)

Biden’s disastrous performance Thursday was not limited to speech hesitations. The president shuffled to the stage and stared blankly at the camera, hardly blinking. Biden’s voice was hoarse and his answers went off-piste, at one point to compare golf handicaps with Trump. “Uncircumcised lips,” a cryptic, and kinda gross, descriptor of Moses’ problems communicating in some translations of the Book of Exodus, felt strangely apt.

It was 90 painful-to-watch minutes of a man who seemed to know the issues but couldn’t articulate them. His delivery was made all the worse in contrast, as Trump, deprived of a crowd and his mic muted per CNN’s rules, exhibited rare discipline and coherence, though much of what he said was untrue.

Democratic Party hands, including many who have worked for Biden, immediately declared the debate a catastrophe for their candidate. Discussion about how the president might gracefully step aside exploded online along with images of viewers covering their faces in exasperation.

It was certainly a far cry from Biden’s 2020 debate performance, where he scored points with a well timed “Will you shut up, man!” Granted, Biden is four years older this time (as is Trump).

For those who’d argue age is disqualifying, Moses was 80, a year younger than Biden, when he came back to Egypt to confront Pharaoh, with Aaron (83) by his side as spokesperson.

All presidents have Aarons — they call them speechwriters, chiefs of staff, cabinet secretaries. But the debate format — a flawed barometer for leadership — favors those who think quickly on their feet, are telegenic and, crucially, do not have a speech disability.

As with Moses, or even King George VI, the ability to speak seamlessly is not the only measure of one’s ability to lead. The insistence on debates is, in a sense, ableist. The ability to make yourself understood comes with the presidential job description, but if the Commander in Chief can send diplomats to negotiate treaties and press secretaries to brief journalists, why can’t he delegate a debate to a well-spoken surrogate, as Moses did sending Aaron to engage an infamously prickly head of state?

Vice President Kamala Harris, a deputy near to an Aaron role, had no problem putting sharp, substantive sentences together in her post-debate interview with Anderson Cooper on CNN last night. “Neither person on the stage tonight made the argument as coherently as you just did,” Cooper said after Harris succinctly described the reality of reproductive rights in American two years after the overturning of Roe v. Wade.

There is no role for an Aaron in televised debates, aside from the vice presidential ones, which attract fewer eyeballs than those for the top of the ticket. Debates remain popular because they are an expedient way to showcase candidates’ positions, personalities and ability to perform under pressure side by side. On Thursday, the matchup was between a man who couldn’t tell the truth about his record and one who couldn’t find the words to make a case for four more years.

Thankfully there are ways beyond debate to evaluate presidential character, particularly in a contest where both candidates have done the job. The law — something Moses was rather famous for — is one, and then there is leading by example.

Midrash relates that Moses’ speech disorder came from a moment in toddlerhood where, after taking the Pharaoh’s crown — an act of effrontery and possibly treason — he was tested with an offering of gems and coals. The angel Gabriel intervened when he reached for the glittering prizes and made him instead grasp for a coal, which he placed in his mouth, burning his tongue.

Fast forward to the 21st century. Trump promised coal-worker jobs (a broken promise for all his damage to the environment). But Biden, an advocate of clean energy, was the one who seemed to have the burnt tongue.

Trump has used Biden’s stutter, like everything else, as ammunition. He imitated it at campaign rallies, in a display reminiscent of his mockery of a reporter with a disability. At one point on Thursday, after a meandering Biden answer on immigration, Trump fired this salvo: “I really don’t know what he said at the end of that sentence — and I don’t think he knows what he said, either.”

For Biden, as a Washington Post piece recently noted, the stutter is a source of qualities Moses was renowned for, empathy and humility. The president has made many memorable connections to young people with stutters, like 9-year-old boy named Henry Abramson, whom he met in Wisconsin in March.

Such meetings showcase Biden’s great gift for human connection, among the most important traits we seek in our leaders. But in the cable news era, being able to tell your story well — often in sound bites — is just as important.

As the post-game pundits pondered whether Biden would withdraw his candidacy, another biblical character came to mind: Saul, the first king of Israel, who eventually lost the favor of his most important constituent: God.

Unfortunately for the Democrats, there is no clear David — young, universally popular and ready to take his elder’s place — waiting in the wings.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO