Harry Schimmelman, we know your wife didn’t die of influenza; she’s looking for you

Once upon a time, immigrant husbands would try to ditch their spouses in America. Enter the National Desertion Bureau

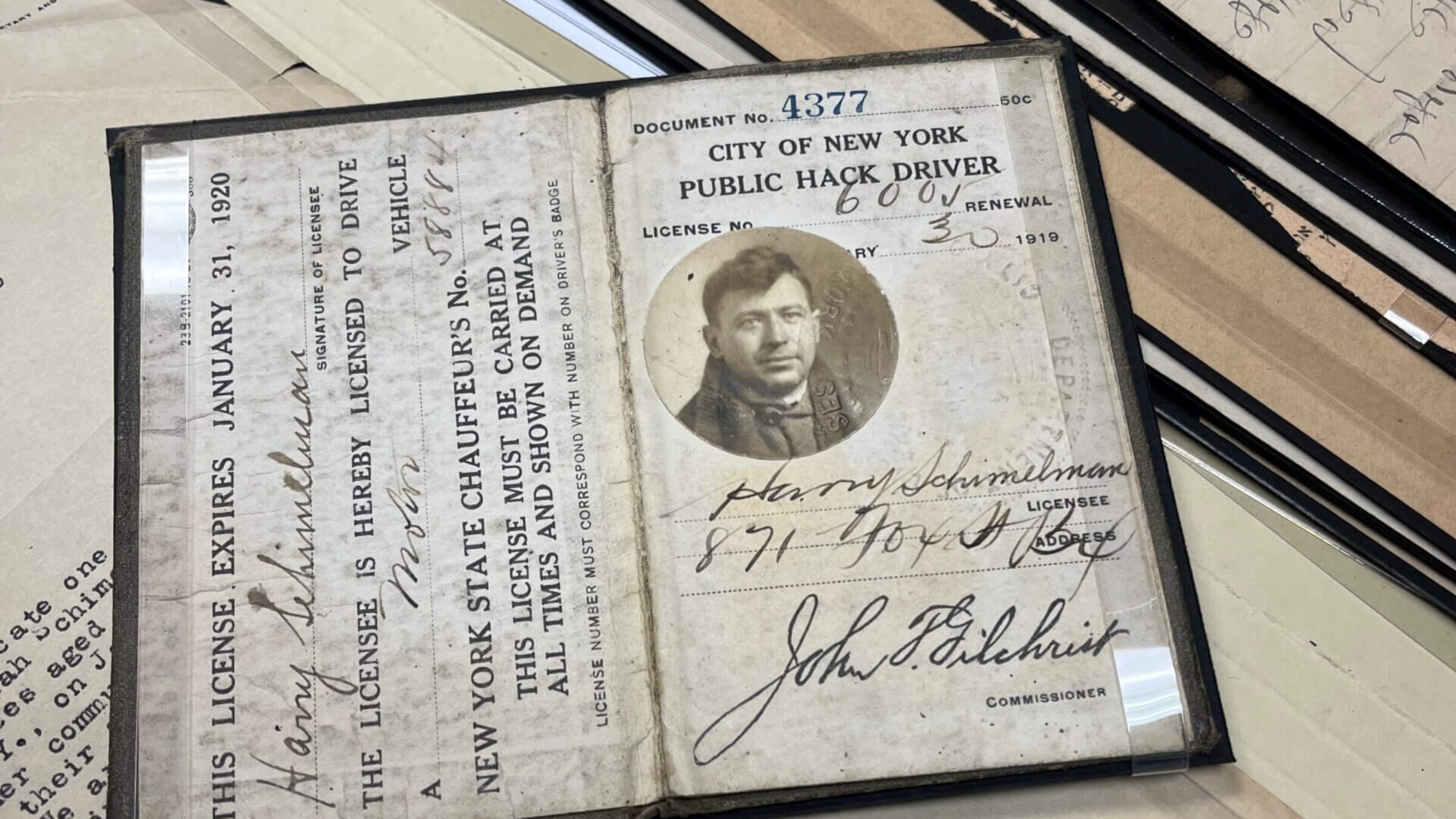

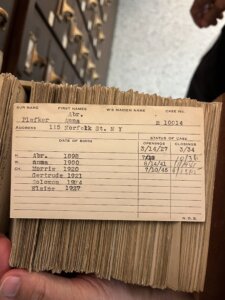

Harry Schimmelman’s hack license. Photo by Andrew Silverstein

Harry Schimmelman and Sarah Levine came to New York as teens — Harry from Galicia in 1906 and Sarah from Minsk in 1909. They were neighbors in Jewish Harlem. After Harry left the army, they married in January 1916.

They settled in the South Bronx. Harry worked as a cab driver and owned a garage, and Sarah raised their two children, Frances and Samuel. But then, in January 1920, Harry disappeared without a word.

He moved to Cleveland, went by the alias “Coppel,” and told everyone he was a widower with two children in New York. His wife, he said, had died in 1918 of the flu.

Sarah, left to fend for herself with a 3-year-old and a 1-year-old, filed a report with the National Desertion Bureau (NDB), an agency founded in 1911 by United Hebrew Charities that, through the 1960s, tracked down Jewish husbands who abandoned their families — a problem that plagued the immigrant community.

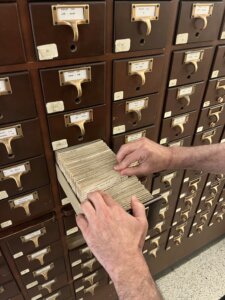

The NDB is the subject of “Runaway Husbands, Desperate Families: The Story of the National Desertion Bureau” an exhibition at the YIVO Institute of Jewish Research.

“It reveals an aspect of Jewish immigration that is not usually discussed,” said Eddy Portnoy, Director of Exhibitions at YIVO, which houses the over 18,000 case files of the NDB and who collaborated on the exhibition with The Jewish Board of Family and Children’s Services, a mental health and social services agency.

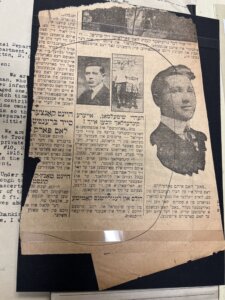

The NDB staff chased down leads on the whereabouts of husbands on the lam, but it also crowdsourced intel through the Forward, then the most widely read daily national newspaper amongst Yiddish speaking immigrants,

The Forward began a regular “Gallery of Missing Husbands” column in 1908, and in 1923, the newspaper’s editor-in-chief and patriarch, Abraham Cahan, became a board member of the NDB.

The following year, the Forward published Schimmelman’s photo. “Harry Schimmelman, your children are looking for you,” the accompanying text in Yiddish began. By then, he had skipped out of Cleveland, perhaps tipped off that the NDB was on his tail. Based on the yearly Rosh Hashanah greeting card he sent to his wife Sarah, he was thought to be living in San Diego and then Chicago.

In her 2007 book about the NDB, “Wives without Husbands,” Anna R. Igra describes the Forward’s “Gallery of Missing Husbands” as a deterrent to would-be deserters. If they did not support their wives and children, “they would be humiliated before the community.” The Forward column often shamed the straying husband to return to his family.

Some, however, did not think it appropriate for the socialist newspaper to run the sensationalist column. According to Igra, a Carleton College history professor, Cahan himself was initially suspicious of uptown social workers who “wished to meddle in the family lives of his working-class readers,” but he saw it as necessary.

“One of the major causes of impoverishment was desertion,” said Jewish Board CEO Jeffrey Brenner on a Zoom call. “Mothers were in extreme poverty, and they were bringing their kids to the orphanages because they couldn’t feed them.”

The Jewish Board organized the exhibition on the 150th anniversary of its precursor and NDB founding organization, United Hebrew Charities.

“There’s a myth of the Jews being the good immigrant,” said Brenner, “pulling ourselves up by the bootstraps.”

“When you actually look at what happened in this era, it’s much messier,” he added. “It’s much harder than any of us want to acknowledge.”

Brenner hopes the exhibition will increase empathy for today’s struggling immigrants and refugees who receive help from his organization.

The Jewish Board will also make available an online genealogical database of case files. Individuals or researchers can then access the actual files of their “deadbeat” ancestors in YIVO archives, which often include ephemera.

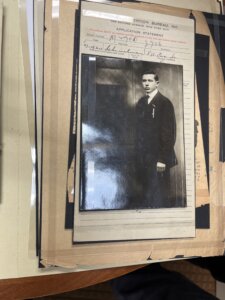

Harry Schimmelman’s file, on display in the exhibition, includes not just file notes and correspondences but photos of Schimmelman and his 1920s hack license. Portnoy showcases other case files to exhibit: one of Nathan Goldfarb, who in 1912 skipped out on his wife and three children and joined a California “free love colony” with his lover; and Abraham Myerson, an impoverished Chicago fabric cutter who repeatedly left his wife and four children.

Jews weren’t the only immigrant community with absentee husbands. Still, according to Igra, Protestant charities refused to support abandoned women and children, fearing that it would give a perverse incentive for men to leave their families. Irish and Italian Catholics did offer help, but unlike the Jewish community, they treated desertion as an individual failing, not a social problem. Jewish organizations were motivated to help their abandoned women and children because they feared if they became public charges, it would lead to antisemitism.

Before the NDB, Jewish women flocked to Professor Abraham Hochman, a fortune teller on Stanton Street on the Lower East Side. The exhibition describes how Hochman, who read palms and practiced phrenology, specialized in tracking down the long-lost husbands of the East Side. “Venus is ascendant — husbands beware,” Hochman declared in 1903, after finding a truant spouse.

The NDB, which functioned as a quasi-detective agency and social service, focused their efforts on Ashkenazi Jews. However, they also helped Sephardic Jews and gentiles. Some women only filed cases because they had to prove they actively searched for their husbands to qualify for public help; others desperately hoped to reconcile their marriages. The client’s application included the reasons for desertion, such as “did not like Baltimore” or “gambling.” Gavin Beinart-Smollan, a historian who consulted with the Jewish Board, found by far the most common reason was “another woman.”

On rare occasions, the NDB helped women file for divorce. Their main goal was reconciliation of families; short of that, they tried to legally force husbands to pay alimony and child support.

By using their network of Jewish organizations and connections across the US and Canada along with the Forward’s “Gallery of Missing Husbands,” the NDB was able to locate about 75% of the deserters, according to Igra. However, they were rarely able to force husbands to pay support, given the weak laws of the era.

Igra, who researches U.S. women’s history, sees the NDB as operating on an antiquated assumption of men being the breadwinners, when most Jewish mothers and teenage children also contributed to household earnings. “The welfare system was trying to use marriage as a way to take care of women’s and children’s poverty,” she said at a recent talk at YIVO.

Still, she sees the NDB as trailblazing. Abandoned and abused women turned to the NDB before the advent of women’s shelters or protective court orders. “They understood the Desertion Bureau as being an agency that was on the side of women in their struggles with their husbands,” Igra said.

The NDB lawyers lobbied for greater legal protections of abandoned women and children. Eventually, women could turn to the Department of Welfare or more sympathetic Family Courts. The NDB itself became unnecessary and their work was mostly forgotten.

“Runaway Husbands, Desperate Families: The Story of the National Desertion Bureau” will be on display at YIVO through the fall.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO