This Mexican diplomat helped Jews flee Hitler. Does that make him Mexico’s Schindler?

Some say Gilberto Bosques was just doing his job. Others call him a hero

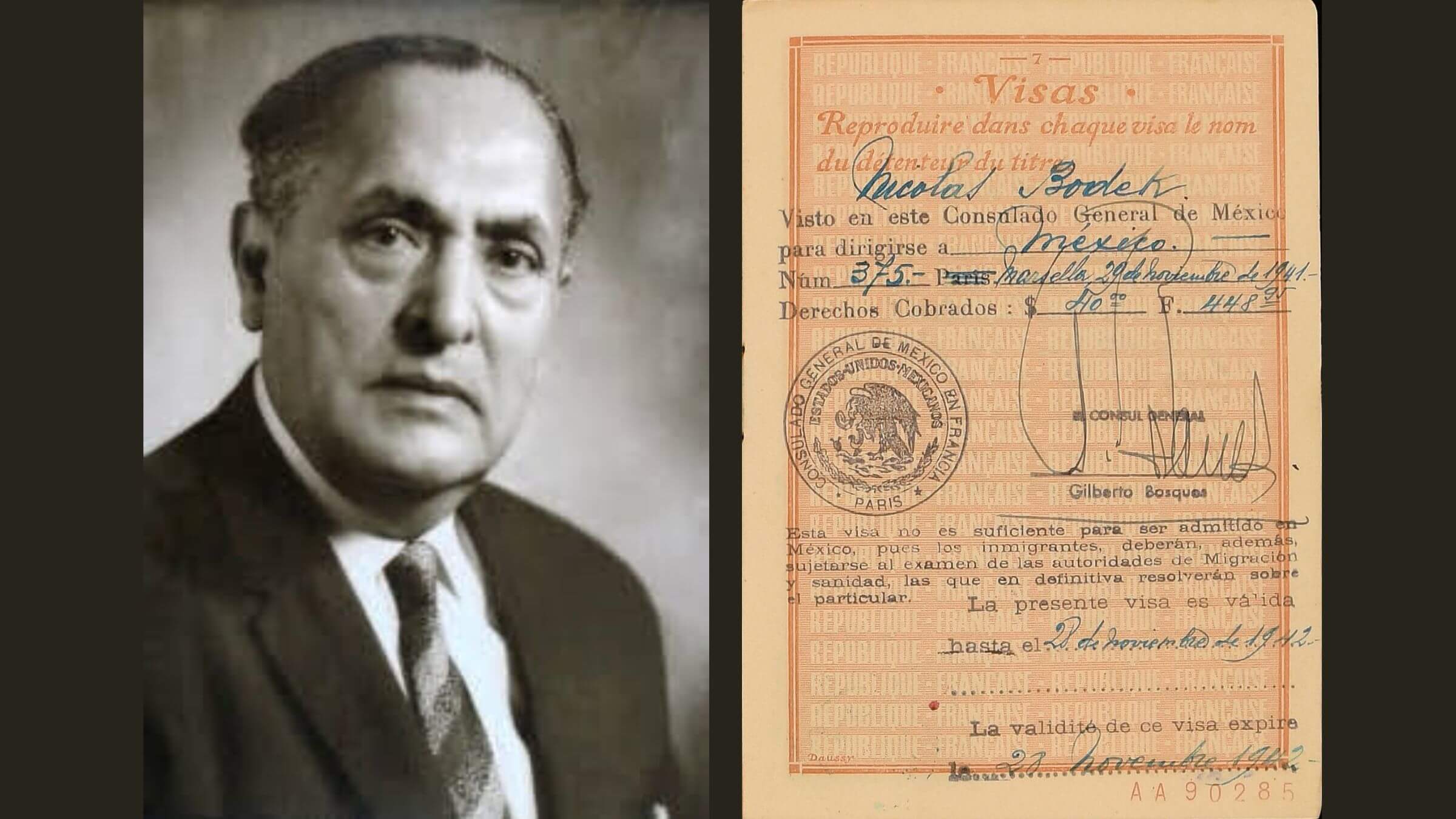

Gilberto Bosques and a visa he signed as Mexico’s consul in Marseille during World War II. Courtesy of Gilberto Bosques (portrait); Archive of Centro de Documentación e Investigación Judío de México (visa).

As head of the Mexican Consulate in France during World War II, Gilberto Bosques signed visas for leftists fleeing Fascist Spain and Jews fleeing Hitler. He rented chateaus near the consulate in Marseille to house and feed refugees, and he issued papers that provided protection to those who wanted to stay in wartime Europe to fight with the resistance.

“We gave them documents and a visa,” Bosques said in an interview in 1987, when he was 95. “And the police would leave them alone.”

But the consulate abruptly ceased operations in February 1943 when Mexico broke off relations with Vichy France. “The Germans broke in just as we were burning our files,” he recalled.

The Nazis arrested Bosques, his wife, their three children and 40 others, transported them to a hotel outside Bonn, and held them prisoner for 14 months. They weren’t harmed, but rations were minimal: “During our entire captivity, only once did we have an egg and a cup of coffee,” Bosques said.

‘We needed a hero’

Bosques and his entourage were released in April 1944 in an exchange of German prisoners of war brokered by the U.S. He returned home to a hero’s welcome, cheered by a crowd of thousands in Mexico City.

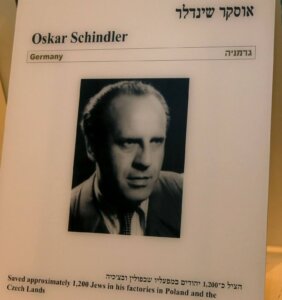

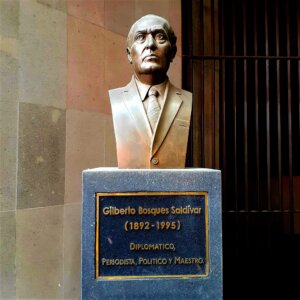

Over the years, he was honored with awards, busts and sculptures, articles, books and films. There’s a street named for him in Vienna and a plaza in Marseille. In Mexico, Holocaust Remembrance Day is also a day to celebrate Bosques, and in 2008, Abe Foxman, then head of the Anti-Defamation League, saluted Bosques as “Mexico’s Schindler.”

Yet his legacy is not without controversy. Did he act on his own initiative or was he following his government’s orders? Did he sign thousands of visas, or just a few hundred? He served as a trusted intermediary disbursing funds from American committees to refugees, but he’s also accused of denying visas and mishandling money sent to pay for them. Meanwhile, Yad Vashem, the Holocaust memorial in Israel, declined to honor him with the title “Righteous Among Nations,” which is conferred on non-Jews who risked their lives to rescue Jews in the Holocaust.

Monica Unikel, who’s widely respected in Mexico City’s Jewish community for turning an abandoned synagogue into a Jewish cultural center, said in an interview that she thinks Bosques’ legacy has been “mythified.” Historically, Unikel said, Mexico has had so few political leaders worth admiring that “we needed to invent a hero, and that hero is Gilberto Bosques.”

But others are steadfast in their regard. “He was a man who loved the Jews and he did his best to help them,” said Lillian Liberman. She interviewed Bosques when he was 100 years old (“He was very lucid,” she said) and made a film about him called Visa al Paraiso (Visa to Paradise) that helped bolster his reputation.

Many refugees have sworn, as did Bruno Schwebel, an Austrian Jew, that without Bosques’ intervention, “my family and I probably would not have survived.” But is the gratitude of those he saved enough to make him worthy of adulation? Or should there be — as Yad Vashem requires — more evidence than that?

Why Yad Vashem denied his nomination

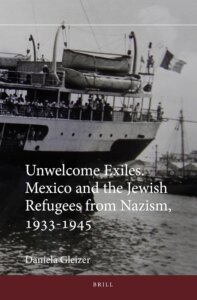

One of the biggest questions about Bosques is whether he acted independently. Historian Daniela Gleizer, who wrote Unwelcome Exiles: Mexico and the Jewish Refugees from Nazism, published in 2013, is certain he did not: “All the visas Bosques gave had the authorization of the interior ministry in Mexico; he did not give those visas as a personal gift to the refugees. He was following the orders of the Mexican government. That’s what consuls do.”

Eric Saul, founder of Visas for Life, a project honoring diplomatic efforts to rescue Jews, vociferously disagrees. He believes Bosques “advocated” for Jews and issued visas in defiance of orders from Mexico’s foreign ministry. Saul nominated Bosques for Yad Vashem’s “Righteous Gentile” honor in 2006, and resubmitted the request several times with more information.

But Yad Vashem was not persuaded. The organization’s criteria for honoring diplomats require proof, and not just anecdotal accounts, that officials undertook “activities that were against their government’s policies or instructions,” explained Yad Vashem spokesperson Ashley Bartov in an email. “In Bosques’ case, insufficient evidence was found in this regard.” And yet, Bartov added: “This does not diminish his efforts, empathy, and positive impact on the lives he saved among the Jewish community.”

Mordecai Paldiel was director of Yad Vashem’s Department of the Righteous when the nomination was made. It remains unclear, he said by email, “whether Bosques was authorized and had a free hand to issue visas by the Mexican government, or violated instructions to the contrary.” It was also reported, Paldiel said, that Bosques “turned down requests” from some applicants.

‘I exceeded the procedures’

Gilberto Bosques’ grandson, who shares his name and who spent a great deal of time with him growing up, said in an interview that it’s possible some visas were denied early in the consul’s tenure, when he was strictly “following the procedures of the government.”

But as time went on, Bosques believes his grandfather realized that writing to officials back in Mexico and waiting for authorization took too long. By the time permission was granted, “people would be dead or sent to concentration camps.” So he started issuing papers on his own. “If I exceeded myself in the procedures of my country, I take full responsibility,” the consul later said.

Liberman, the filmmaker, said Mexico’s ministers of the interior and foreign affairs “were totally against receiving any Jews,” but Bosques lobbied hard. “He would write to the director of the health department and say, ‘This is an important doctor and we don’t have this specialty in Mexico,’” said Liberman. “I read those letters; I have them.”

Jewish stereotypes?

But Gleizer cites letters from Bosques conveying the opposite, where she says he explains “why he canceled the visas of people because they were Jewish — they would not assimilate, they were undesirable.” That was “the language of the time,” so in that sense, she said, it’s not surprising. “But it is very surprising if you compare it with the image of a Holocaust hero.”

In his 1987 interview, Bosques appeared to stereotype Jews, saying he opposed a proposal to “establish agricultural colonies for Jewish immigrants to Mexico” because “the Israelites have traditionally been involved in business and this was outside their experience. Working the soil is outside the Jewish mentality. Normally they work in industrial or commercial enterprises.” Instead, he felt Jews were better suited to fill Mexico’s “needs for industrial development, for realizing our natural resource potential.” He even proposed “moving the diamond industry to Mexico” to employ them.

So was he an antisemite? “It can’t be,” his grandson said. Bosques joined the Mexican Revolution as a teenage soldier, and “all his actions, throughout his life, were based on those experiences. He always fought for freedom and liberty and justice. That doesn’t only apply to Mexican nationals. It applies to everybody.”

The numbers discrepancy

How many visas Bosques signed, and how many went to Jews, is unclear. The Holocaust Encyclopedia, a project of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, says Bosques “saved the lives of tens of thousands of Jews and refugees fleeing the Franco dictatorship in Spain.” Wikipedia says that under “his auspices, visas were issued to approximately 40,000 people, mostly Jews and Spaniards.” The website’s sources include Richard Grabman’s 2007 book, Bosques’ War: How a Mexican diplomat saved 40,000 from the Nazis, which translates into English the 1987 oral history with Bosques that was published by the Mexican government.

Those citations lumping the fates of Jews and others together make it sound like Jews got thousands of visas. But Gleizer said she found records for just 300 Jews who made it to Mexico on Bosques visas. And numerous sources state that no more than 2,000 Jews came to Mexico between 1933 and 1945. So how could Bosques, who served as consul for just a third of those 12 years, have signed “thousands” of visas? Where did those people go?

Bosques’ grandson said the discrepancy is easily explained. That the consul signed 40,000 visas “doesn’t mean 40,000 people arrived in Mexico or the U.S.,” he said. “It means that thanks to those papers that he facilitated, directly or indirectly — he also gave visas or passing papers to other organizations, including Varian Fry and the Quakers — these documents helped people get away from danger.”

But Gleizer said it’s impossible to know how many got visas if they didn’t use them to emigrate. “You only have the testimony of those who came,” she said. “You don’t have the stories of those who couldn’t because they are not here.” She also said she found letters from organizations, including the Jewish Labor Committee in New York, complaining that they paid for visas Bosques never issued.

Love for the lefties

Tessy Schlosser, director of the Mexican Jewish Documentation and Research Center in Mexico City, said Gleizer’s research is “controversial.” But she too is skeptical of the idea that Jews were granted visas on humanitarian grounds. Jews were only allowed in, she said, if they were deemed “good migrants for Mexico.”

Some of those “good migrants” were the doctors and other professionals whose cases Liberman cited. Other Jews were given visas because their politics aligned with the left-wing agenda of Mexico’s wartime president, Lazaro Cardenas. In fact, Cardenas made asylum a priority for anyone who opposed Franco, whether they were Spanish or Jewish.

Claudia Bodek says her family is a good example. Her Jewish grandparents had left Berlin for Spain in 1933; her grandfather served as a doctor in an international brigade fighting against Franco. Later the family fled to France, but her grandmother panicked when Bodek’s father was about to turn 16, the age at which he could be picked up by authorities.

Suddenly, “Gilberto Bosques called them from out of the blue and said, ‘I’ve got visas for you, come and pick them up,’” Bodek said. “They were German Jews, but they were leftists, very politically involved.” Their past activism apparently saved them.

Bosques also issued visas to a number of well-known cultural figures, including artist Alfredo Silbermann, writer Max Aub, whom Bosques extricated from Nazi camps on two occasions, and writer Anna Seghers, whose 1944 novel, Transit, about refugees in Marseille, was made into a film in 2018. “If we can leave, it is thanks to your protection and help,” Seghers’ husband Alfred Kantorowicz wrote to Bosques in 1941.

Recognition by U.S. Congress

While these anecdotes don’t pass strict tests for heroism like Yad Vashem’s and Gleizer’s, they are enough to put Bosques on a list of 60 diplomats who did what they could to get Jews out of Europe. On June 11, the U.S. Congress passed the Forgotten Heroes of the Holocaust Congressional Gold Medal Act, which would award those 60 officials with posthumous Congressional gold medals. The bill was introduced by Reps. María Elvira Salazar (R-FL) and Ritchie Torres (D-NY) and was supported by nearly 300 representatives. A version of the bill was also introduced in the Senate.

The gold medal project pleases Saul, the Visas for Life founder, but he’d like to see even more diplomats recognized. Jews “survived because somebody did not stand idly by,” he said. “Honoring goodness is a cardinal virtue in Judaism, and that’s been my mission.”

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO