Could a Jewish voice from a previous century be a prophet for our times?

Aaron David Gordon may have been well ahead of his time on both environmentalism and Arab-Jewish relations

The teachings of Aaron David Gordon inspired followers, including these as seen in 1939. Photo by Wikimedia Commons

His thoughts about Jews loving nature, manual labor, and getting along with Arabs captivated his contemporaries, but is he a voice for our time?

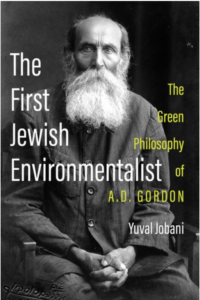

The title of The First Jewish Environmentalist, a new book by Tel Aviv University professor Yuval Jobani that pays homage to Ukraine-born Aaron David Gordon, might be slight hyperbole since the Talmud and Mishnah offered precepts about caring for the natural world before Gordon, who died just over a century ago.

But Jobani plausibly implies that since Gordon was the ultimate individualist, it is up to each reader to decide whether to follow his path or not. More than just a celebrant of Mother Earth, Gordon had undoubted charisma. At age 48, a frail, emaciated vegetarian turned vegan, he opted to become a field laborer in Ottoman Palestine after having spent his life at sedentary office jobs in the Russian Empire.

The allure of manual labor has entranced such Jewish writers as Emma Goldman, Paul Ehrlich, Simone Weil and Primo Levi to Studs Terkel, Murray Bookchin and Richard Sennett. Yet Gordon really walked the walk, and delighted even when clearly failing at toil in the vineyards and orange groves of Petah Tikva. Much younger fellow workers would cheerfully make up Gordon’s work quotients for him when he was unable to do so.

Pottering around the fields ineffectually, Gordon’s Diogenes-like figure inspired affection from his colleagues. Later observers, like the publisher Shaoul Hareli, would even deem him “a saint.”

Although personally drawn to gloom and despondent people, Gordon-as-martyr would also charm friends and colleagues by dancing at communal get-togethers “into an ecstasy to the point of collapse,” Yosef Aharonowitz, a contemporary, recalled.

Yet Gordon also wrote, “Give us people who despair,” suggesting that only Jews profoundly out of synch with their world would realize how removed 19th century Jewish urban life was from life’s essentials. Unable to own land in Tsarist Russia, Jews were, according to Gordon, shut off from basic thrills like breathing clean air and relishing soul-satisfying landscapes.

Gordon’s predilection for nature, however, did not mean that he had scientific understanding of what he was kvelling at. The Israeli zoologist Heinrich Mendelssohn carped: “Gordon was completely unrealistic, a total Romantic. He did not know the first thing about the natural world.”

This hardly mattered to such fans as the poet Rachel Bluwstein, whom Gordon once approvingly described as “standing before me, very tall and straight, upon the edge of the abyss,” just as he alleged that all true individualists must walk “over the mouth of a deep abyss, or upon tall mountain tops covered with eternal snows.”

Gordon’s quirky nonconformism ensured that he would reject socialist ideology, which was often at the heart of Jewish labor movements. Free-spirited to a fault, Gordon never lacked chutzpah. His key text Man and Nature second-guessed the Buddha for “wrongly assuming” that longing for life meant to wish to transcend earthly woes.

Sometimes teetering on the brink of eccentricity, Gordon for years mainly drew the attention of specialized researchers. More recently, though, Gordon’s renown has brightened, especially after a Brandeis University symposium three years ago that marked new editions of his writings, shortly after another homage from Academic Studies Press by philosophy maven Yossi Turner.

In addition to environmentalism and labor, Gordon also delved into the issue of Arab-Jewish cooperation. An anti-militarist to the core, Gordon decried volunteers who served in the Jewish Legion of the British army during WWI.“The military is the blind, deterministic and brutish force of the people,” Gordon said, maintaining that “the collective fist directed outwards is also directed inwards.”

Fearing the power of government over the people, Gordon also deliberately rejected violence as a response to assaults. In a 1918 essay criticizing Jewish militarism, he asked if Jews “want to be a people with an evil fist?”

This anti-pugilistic stance was born of bitter experience. After being physically attacked by Arabs in 1909, Gordon resolved that the solution was not to answer in kind. Instead, he focused on positive interactions between Arabs and Jews in the Middle East. Judging all Arabs by things some may have done to Jewish settlers would be like antisemites finding justifications for despising all Jews.

“Our attitude towards [Arabs] must be one of humanity, of moral courage which remains on the highest plane even if the behavior of the other side is not all that is desired,” said Gordon. “Indeed their hostility is all the more a reason for our humanity.”

“Wherever settlements are founded, a specific share of the land must be assigned to the Arabs from the outset,” Gordon wrote in 1922. “The distribution of sites should be equitable so that not only the welfare of the Jewish settlers but equally that of the resident Arabs will be safeguarded. The settlement has the moral obligation to assist the Arabs in any way it can. This is the only proper and fruitful way to establish good neighborly relations with the Arabs.”

This well-intentioned advice was wholly overlooked, just as most of Gordon’s five volumes of collected writings still await translation into English. Although some of his work may seem impossibly lofty, there is a basic vitality to his writing praised by the French Jewish philosopher André Neher, who paired Gordon with the essayist Ahad Ha’am as “excellent coiners of terms and phraseology.” Neher observed that Gordon’s acuity with developing the revived Hebrew language “is not only a matter of a single term but a whole terminology or, rather, a terminological and linguistic presence which possessed its own indubitable characteristics.”

This refreshing inventiveness was part of Gordon’s allure; he was admired even by those who did not share his optimism about nature and labor curing millennia of tragedy and grief in Jewish history (“Work will heal us,” he wrote), or generous-hearted overtures to friendship between Arabs and Jews.

In 1931’s Jewish Humanism, the historian Hans Kohn lauded Gordon, alongside Ahad Ha’am and the philosophers Moses Hess and Martin Buber, for finding redeeming features in nationalism that made possible individual creativity in an ethnic community.

Yet Kohn, who co-edited a book on nationalism with Gordon, fled Palestine as early as 1932, convinced that Jews and Arabs could never get along peaceably there. In the dismaying vortex of today’s Middle East, might the alternative viewpoints of Aaron David Gordon, who called out to Jews who are experiencing despair, be a mechaye for readers of all backgrounds?

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO