Was the Leopold and Loeb case really the ‘Jewish crime of the century?’

100 years later, the frenzy surrounding the murder of Bobby Franks still raises uncomfortable questions about antisemitism

Nathan Leopold Jr. and Richard Loeb, who were convicted for the kidnapping and murder of Loeb’s cousin, 14-year-old Bobby Franks. Photo by Getty Images

It has been called the “Jewish crime of the century.” But the centenary of the trial and conviction of Nathan Freudenthal Leopold Jr. and Richard Albert Loeb, is a time to reconsider the case of those two prosperous teenaged students at the University of Chicago who kidnapped and murdered 14-year-old Bobby Franks, a second cousin of Loeb’s.

In a 1999 overview of the case, newly reprinted by University of Illinois Press, Hal Higdon speculated: “Leopold and Loeb were Jewish, so antisemitism may have been involved in the excessive publicity given the case.”

To be sure, the hype surrounding the events was cataclysmic, and to some extent remains so, due to books, plays, films, TV documentaries, and other reminders of the crime. Even season 6 of Better Call Saul features one character accusing others of behaving “like Leopold and Loeb, two sociopaths.”

America’s Jewish community united in horror at the murder of Bobby Franks, likely fearing that its depravity might somehow reflect on them.

An anonymous “Jewish spokesman” cited in 1924 in the Chicago Daily Tribune felt that the main problem was that Leopold and Loeb came from families that were insufficiently frum:

“Hundreds of thousands of rich Jews who don’t know what to do with their money, and who let their children grow up without any feeling of Jewish responsibilities” were at fault, it seems.

Other periodicals, like American Standard, sponsored by the Ku Klux Klan, were less ambiguous: “Two rich young Jews have confessed that they kidnapped and murdered 14-year-old Robert Franks of Chicago. They had boasted of being atheists. Once again Jewish degeneracy and anti-Christianity have done their work in America.”

After the judge decided to spare the lives of the accused, the American Standard weighed in again, noting that “these two intellectual young Jews escaped the extreme penalty,” with the term “intellectual” apparently intended to look almost as pejorative as “Jew.”

Even after Loeb was knifed to death in prison in 1936 while serving a sentence of life plus 99 years, notable acrimony from US Jews was evident. The American Jewish journalist and film producer Mark Hellinger wrote in the Syracuse Journal, alluding to the gay panic defense, later discounted, of Loeb’s murderer, who claimed that his fellow prisoner had propositioned him.

Hellinger cited what he called a jape sent to him by an “unknown correspondent in Chicago” that “Loeb made a slight mistake in grammar. He ended a sentence with a proposition.”

Scarcely more compassionate, in the early 1950s novelist Meyer Levin, a classmate at the University of Chicago, requested Leopold’s cooperation in writing a novel based on the murder.

Leopold, still in prison, replied that he did not wish his story to be fictionalized, but offered Levin an opportunity to contribute to his memoir, a work-in-progress. Levin, who had already been thwarted in long-term plans to write about Anne Frank, steamed ahead and published a ponderously Freudian novel, Compulsion (1956), which inspired an equally leaden Hollywood film (1959).

One Jewish character in Compulsion asserts, “It’s lucky it was a Jewish boy they picked,” since if Leopold and Loeb had killed a Christian, the repercussions on their community would have been far worse, most Jews felt. Levin’s amateur psychoanalysis concluded that by murdering Bobby Franks, Leopold and Loeb were expressing “Jewish self-hatred.”

American Jews and others turned to Freud-like approaches to make sense of the otherwise inexplicable tragedy, which purportedly occurred because Leopold and Loeb had resolved to commit the perfect crime.

This plan failed almost immediately as Leopold absent-mindedly discarded a pair of his eyeglasses at the crime scene, leading to a fairly rapid arrest and confessions. A rumor about romance between the murderers, definitely not a subject for conversation in upper-class Chicago society of 1924, added to the impression that Freud, the famed Jewish headshrinker, might be the one to figure it all out.

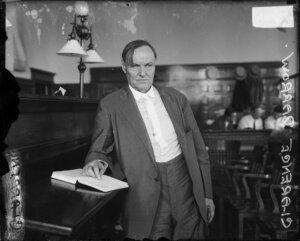

The publisher William Randolph Hearst, who owned two Chicago dailies, and Colonel Robert McCormick, the publisher of the Chicago Tribune offered to pay Freud to travel to Chicago to comment on the trial. The Tribune assigned staff reporter George Seldes, of Russian Jewish origin, to personally invite Freud in Vienna to serve as an expert witness for the trial.

However, the father of psychoanalysis had just been diagnosed with cancer of the jaw and disliked America, so he penned a letter to Seldes in 1924, reasonably explaining that he could not be expected “to provide an expert opinion about persons and a deed when I have only newspaper reports to go on and have no opportunity to make a personal examination.”

Freud went on to explain that for health reasons, he had already rejected a similar offer from Hearst, who had proposed chartering an ocean liner for the psychoanalyst’s exclusive use. The ballyhoo surrounding the trial continued undeterred, with another Chicago paper, suggesting that Comiskey Park, home of the Chicago White Sox baseball team, might be transformed for the occasion into an open-air courtroom.

Instead, in a traditional venue, attorney Clarence Darrow took three days to deliver a final plea to the judge for the lives of his clients. In Darrow’s speech of nearly 40,000 words, there was not a single mention of Jews or Judaism. Yet in pointing out how Leopold’s father would see his “life’s hopes crumble into dust” with a potential death sentence, Darrow, the celebrated agnostic, may have echoed the Book of Isaiah 5:24-30, describing the Wrath of God which causes “achievements [to] crumble into dust.”

Darrow’s focus on the families of the perpetrators as blameless victims extended the circle of suffering to the Jewish community. This concentration on mishpocheh was an essentially Jewish approach to a tragedy affecting many.

Decades later, Leopold would inform the parole board that he was a “practicing, believing Jew.”

Whether or not this belief continued, the story of the two scions of Kenwood, an exclusive Jewish neighborhood on the South Side of Chicago, continued to transfix many. In a late reminiscence, the near-nonagenarian Jewish writer Saul Bellow recalled how when he was nine years old, his family moved from Montreal to the Humboldt Park neighborhood on the West Side of Chicago. There, after school, in the cellar of a synagogue, he studied Old Testament Hebrew and, Bellow adds: “At home I followed the Leopold and Loeb case in the papers.”

This mishmash of influences was echoed, Bellow noted, by local Chicago newspapers which during the trial printed Darrow’s courtroom speeches alongside reports of gang killings and the “urban sketches of [American Jewish reporter] Ben Hecht.”

Although experts like the cultural historian Sander Gilman have opined about how Leopold and Loeb reflected and impacted American Jewry, readers still await an in-depth full-length study that extricates the murderers from their thorny psychological motivations and sees their most unfortunate story in terms of their Judaism.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO